Depending on whom you ask, geoengineering is either a threat to serious climate action, a distant backup plan, or a necessary part of today’s climate policy. Everyone would agree that it is controversial. Geoengineering encompasses a broad range of proposed large-scale deliberate interventions to mitigate or even reverse temperature rise.

Many scientists and activists are concerned that climate interventions based on these “technological solutions” will divert attention from emissions reduction and further disrupt an already complex and poorly understood global climate system. “It would be a truly dangerous experiment, and it’s impossible to really test it beforehand,” says Linda Schneider, an expert on climate policy. […]

Geoengineering tends to be divided into two main directions: techniques aimed at removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and the much more controversial proposals for reflecting sunlight away from Earth. Here we will examine in depth the main proposed techniques in each category, their purpose, and concerns regarding the potential negative impacts they could bring.

Carbon dioxide removal

Many researchers argue that the use of carbon removal technologies is now almost essential, given that the world is off track to reduce emissions enough to avoid dangerous temperature increases. “By the time we reach net-zero emissions, we will have experienced an unacceptable rise in temperature,” says Douglas MacMartin, a mechanical and aerospace engineer at Cornell University, who specializes in solar geoengineering. “The long-term solution to this is to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere.” […]

BECCS

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, often known by the acronym BECCS, is considered one of the most sustainable negative emissions technologies.

BECCS involves growing crops or trees, which absorb CO2 from the air as they grow, and then burning them to produce energy, while simultaneously capturing the emitted carbon. The carbon would then be stored underground, preventing its return to the atmosphere, before the whole process is repeated. Over time and on a sufficiently large scale, this technique could theoretically remove significant amounts of carbon from the atmosphere.

BECCS has become particularly popular among climate model researchers and is now included as a core part of most carbon offset plans compatible with the Paris Agreement. […] Despite its widespread use in climate models, BECCS has not yet been proven at scale, with only a handful of units operating worldwide. The initial cost for constructing carbon capture facilities is also high, while storing carbon underground could cause earthquakes or lead to CO2 leakage back into the atmosphere.

Another major concern regarding BECCS is the vast amounts of land that would be needed for bioenergy production, which could compete with food provision or lead to deforestation. A study found that the bioenergy crops required to achieve the CO2 removal scale included in plans to limit temperature rise to 2 degrees could occupy up to 700 million hectares—equivalent to about half of the world’s current croplands. According to the study, further expansion of bioenergy to achieve the 1.5-degree limit could cause overall carbon losses from land, replacing forests and other high-carbon ecosystems with crops.

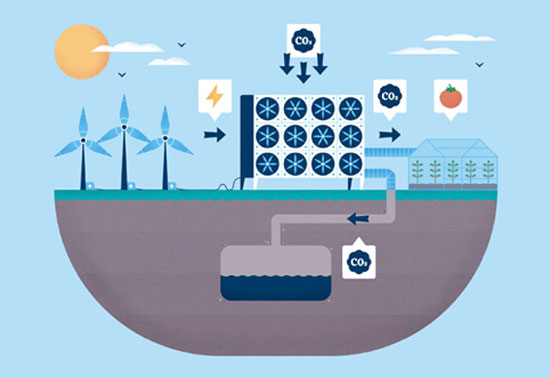

DAC

This is the other major large-scale negative emissions technology being proposed. Direct air capture (DAC) involves machines that remove carbon dioxide directly from the air, rather than from a point source, such as a power plant, as is the case with BECCS. In order to be a negative emissions technology, the CO2 would then need to be stored in a way that prevents it from returning to the atmosphere, similar to BECCS.

Compared to BECCS, direct air capture can appear an attractive option because it does not rely on massive changes in land use and avoids potential complications around deforestation. Theoretically, facilities could also be constructed more easily near storage and utilization sites, reducing the need to transport CO2 over long distances, such as through pipelines.

However, this is accompanied by several reservations. For its operation, it would likely require enormous amounts of energy: a study published last year found that it could require more than half of today’s total electricity production by 2100. The paper also warned about the risks involved in assuming that it could be developed at scale and then be discovered that this is not feasible. There are also concerns about how the captured CO2 could be used. For example, a partnership between the American startup Carbon Engineering and the fossil fuels company Occidental Petroleum to develop the world’s first large-scale DAC unit will use the captured CO2 to enhance the efficiency of oil recovery.

In fact, enhanced oil recovery is today the largest industrial use of CO2. It is the only large-scale carbon dioxide capture industry that exists, so it offers an economic pathway for developing DAC and BECCS on a broader scale. However, using captured CO2 to extract more oil has obvious problems. The captured CO2 could also be used in other applications, such as for producing fuels or construction materials like cement – a sector known as carbon capture and utilization. However, for emissions to be considered negative, the CO2 must remain locked away long-term – if it is released back into the atmosphere, such as through fuel combustion, the entire process becomes at best carbon neutral. Currently, 15 small DAC units are operating worldwide, but not all the carbon dioxide they capture is stored.

Management of solar radiation

Known also as solar geoengineering, this group of proposed technologies would theoretically reflect sunlight away from Earth’s surface before it has a chance to warm the atmosphere. Supporters of these controversial techniques argue that they should be researched and understood in case the world exceeds carbon projections and temperature rise limits of 1.5 or 2 degrees. But solar geoengineering has serious limitations. All of these techniques would be unable to address ocean acidification [increased pH due to CO2 absorption], since they would not directly reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. They also risk a “termination shock” – a rapid increase in temperature rise if the method fails for some reason – and the alteration of local rainfall or temperature patterns in unexpected or undesirable ways.

Aerosol injection into the stratosphere

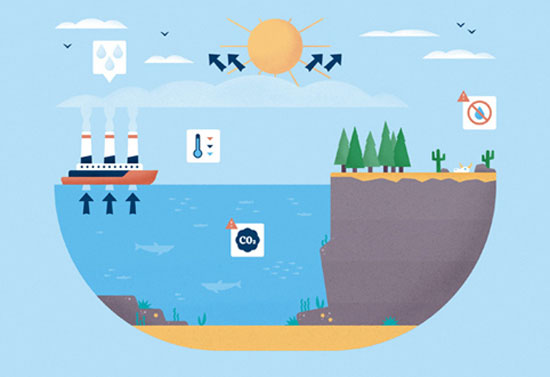

Currently, the most widely discussed approach for managing solar radiation involves injecting sulfur particles or other aerosols into the stratosphere from aircraft or high-altitude balloons.

Stratospheric aerosols are the only solar geoengineering techniques “that we know work today,” says Macmartin of Cornell University. “We see what happens after a large volcanic eruption like Mount Pinatubo: we put sulfur aerosols into the stratosphere and the planet cools by about half a degree.” However, today’s aircraft could not transport enough to the stratosphere, he says—the vehicles with this useful payload are “at least five years” away from development. Creating a solar geoengineering system that would benefit most of the world is likely much further off than that. “There are so many unanswered questions,” says Shuchi Talati, a geoengineering expert at UCS (Union of Concerned Scientists). “We would need a strong governance system, we would need to know how successful solar geoengineering really was at large scale, we would need a large-scale monitoring system. All of these are really expensive. And so I think we are quite far away.”

A series of potential problems are already causing concern. The injected sulfur aerosols could destroy the ozone layer. The sulfur salts would also eventually end up as acid rain, a particular concern for relatively pristine parts of the planet that have not experienced such phenomena in the past. It could also pose a risk to geopolitical systems, says Talati. “If a country decides to unilaterally deploy solar geoengineering, this could completely disrupt weather systems for a specific country, which would disturb its agricultural systems and GDP, resulting in enormous tensions.”

Several research programs continue to develop today the injection of stratospheric aerosols in an effort to better understand the risks and benefits of it, despite calls from certain circles not to proceed with any testing or development before the creation of a reliable global governance mechanism.

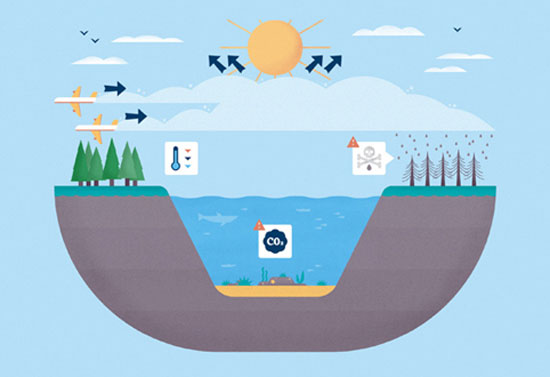

Increase in cloud brightness

Another, less researched proposal for managing solar radiation would see ships spraying seawater into low cloud layers. This would add salt particles around which more water vapor could condense and thus, theoretically, increase the reflectivity of clouds.

However, scientists don’t yet know where and when it works and when it doesn’t, says MacMartin. “Until we can answer this question, it makes it a bit difficult to make many global predictions,” he adds. Australia is already experimenting with this technique on a local scale, hoping it could be used to protect the Great Barrier Reef. However, the effort to extend this technique to cool the entire planet would create other problems, says MacMartin. The right type of clouds may be found over 10% of the Earth’s surface, and “the results don’t stay exactly where this pressure is applied,” he says. “You would likely have greater disruptions in rainfall patterns and other similar things from the cloud albedo effect than you would from stratospheric aerosols.”

Other solar geomechanical technologies

There are numerous other hypothetical techniques, which to a large extent have much less research interest than the two methods mentioned above.

One of the more bizarre proposals is that for space mirrors, according to which a fleet of mirrors would be sent into orbit to deflect light away from Earth. While this could avoid concerns about chemical intervention in the Earth’s atmosphere, it could have negative consequences, such as drought. It is also generally considered prohibitively expensive. “I think one of the reasons why solar geoengineering has the profile it does is because it could be a cheaper way to limit damage, while we extend things like carbon removal and mitigation and adaptation,” says Talati. “In that respect, I think [space mirrors] wouldn’t offer many of the benefits that make stratospheric aerosol injection attractive.”

Another less well-known proposal is the thinning of clouds. Although technically they do not reflect sunlight, the goal here would be to disperse clouds at high altitude by adding additional nuclei, allowing more heat to escape from Earth. However, research has found that cloud seeding could accidentally lead to a greater increase in temperature or affect other aspects of the climate system in unexpected ways.

Local changes could also be made to the Earth’s surface. From installing white roofs to genetically modifying crops to reflect more sunlight, changing the reflectivity of the ground could help address rising temperatures – especially extreme temperatures in densely populated and important agricultural areas. However, the smaller scale of these various proposals usually excludes the possibility of them being considered solar geoengineering.

Large-scale changes have also been proposed to the Earth’s surface reflectivity, from covering deserts with plastic sheets to protecting Arctic ice using hollow reflective glass spheres – a system now being tested. Other proposals would attempt to brighten the ocean surface, such as by creating millions of microscopic air bubbles or spreading microspheres on the water.

[…]

Source: https://chinadialogue.net/en/climate/geoengineering-how-to-stop-global-warming-most-controversial-solutions-explained/

Translation: Harry Tuttle