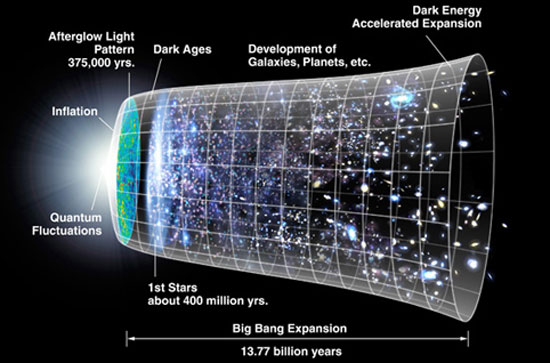

The Big Bang theory will soon close a century of life – perhaps its obituary will coincide with the moment it retires into the history of human scientific conceptions. Its formalization in 1927 is attributed to the Belgian Georges Henri Joseph Edouard Lemaitre, who was simultaneously a priest (Catholic), mathematician, astronomer, and theoretical physicist, indeed a professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain. Ordinarily, a Christian priest who believes in and promotes the “creation of the world in 7 days” by an Almighty should not support something so contradictory as a “great cosmogonic explosion”; unless the Almighty were transformed from “creator of the universe” into a detonator. But Lemaitre did just that. In the early 20th century, some astronomical observations could be made with remarkable accuracy for that era’s standards. Consequently, the observation (or, as would later become apparent, the hypothesis) of an expanding galaxy, and accordingly, an expanding universe, would require a “moment zero,” the starting point of this expansive motion. There, with time, the Big Bang was placed: according to scientific calculations, 13.8 billion years ago…

The question of the creation of the world is purely ideological/cultural, and it is certain that it does not concern any of the hundreds of thousands of different living beings on the planet. It is most likely that it did not concern the ancestors of homo sapiens either. It would not be arbitrary to argue that it must have emerged within the construction of various religious beliefs (including, perhaps, some animistic ones), as synonymous with the ownership of the world (by its creator, one or more). Consequently, there must already have been not only some organization of the human species (let’s say human herds) but also some constructive abilities within them. The question of the creation of the world is, therefore, a concern (not innocent) of homo faber and of power structures within his communities.

There is no evidence of answers to this question earlier than, say roughly, two or two and a half thousand years BC. And all of them, despite their differences, have at their center creators (of the world) generally anthropomorphic: the gods or whatever supernatural entities/forces had been consecrated as sacred.

From this perspective, the Big Bang should be considered not an immutable truth but rather the cultural/technical/scientific idea (about the origin of the world) of the early 20th century capitalist era, since first the explosions, smaller ones to be sure, had become commonplace as human endeavors: wars, and certainly the 1st World War.

From many points of view, the theory of the “creation of the world” from a Big Bang is even more mystical than the older religious-type ones. For someone to grasp, for example, the idea that the Big Bang is the starting point of the creation of cosmic matter (that is, of galaxies, suns, planets, and among them the insignificant rock on which we live), one must radically and definitively abandon the question “and what existed before”: according to the theory, the Big Bang created time itself. The creation of space—and—time from absolute nothingness through an absolute explosion is an intellectually interesting exercise; but at its core, it does not differ, for example, from the Jewish view of the master (and biotechnologist!) almighty who also begins his work from absolute nothingness while being the absolute all; nor from the Babylonian view, for which “in the beginning was chaos”; nor from the Egyptian, for which “in the beginning was the word” (of the god Ra). To put it differently, the Big Bang theory requires (required…) something that is anathema to scientific thinking: a certain amount of faith. But, certainly, also scientific evidence.

For a century, thousands of scientific announcements, specialized books, books for mass education, articles, lectures, journalistic writings, collected, analyzed and recycled these scientific documents (observational records from telescopes for the expansion of the universe and physical-mathematical equations) considering the Big Bang as a proven fact. To cover some “unexplained” inconsistencies in the relationship between theory and observational data, some arbitrary measures were taken (something quite unknown to scientific knowledge…): the concepts of dark matter and dark energy were constructed – creating, as one would expect, new headaches for the astrophysics community, far from public opinion and its beliefs.

All this “kingdom” of creation of the world from the Big Bang has been seriously shaken in recent years. And again, far from the crowd, in the scientific sanctuaries. It is not something quiet and peaceful – it just happens… And although it happens so “far” from daily experience, for a subject so “far” from everyday interests, it has multiple significance. Mainly because it de-sanctifies and de-mythologizes what is called “science” at its core, in its maternal field: physics.

Parenthesis: thus spoke Thomas Kuhn

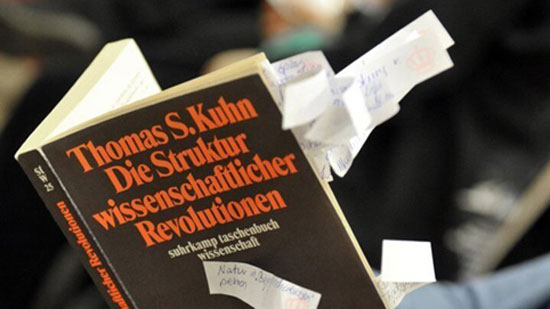

… The basic characteristic of the scientific community is the acceptance of a common Paradigm… Science begins, for Kuhn, with the emergence of the first Paradigm (and the creation of the first scientific community). Until then there is no science, but a plurality of opposing “schools” and opinions.

The Paradigm gains general acceptance, scientists cease to continuously question the foundations of their field and devote themselves to “normal research”, which quickly yields results. The generations of scientists are trained in the light of the accepted Paradigm, learning to have the same values and the same perspective as their educators. This educational alignment passes through textbooks and works considered classics, and plays a huge role in the economy of forces and the efficiency of the field.

The “paradigm” in a Paradigm is not only the acceptance of a theory. It is simultaneously an ontological assumption (what kind of entities the world consists of), a methodological direction (which problems are important and what is considered a scientific solution) and a common language. The paradigm is therefore so comprehensive that Kuhn goes on to talk about entering a new world.

The activity of solving puzzles in physiological science is not, however, a continuously successful process. There are certain problems which, despite their fundamental importance and the repeated efforts of the community, continue to remain unsolved. On the other hand, some experiments and new observations may lead to data that contradict an accepted belief. Such cases constitute anomalies for the Paradigm, and an accumulation of anomalies can lead to the overthrow of the Paradigm. Certainly, anomalies are to some extent natural; no Paradigm is free from anomalies, and most of the time scientists are fully aware of this fact, without losing their faith in the Paradigm. The question that arises, of course, is in which case the accumulation of anomalies is considered so significant as to lead to the overthrow of the Paradigm.

The question is crucial and does not admit a general solution. The history of sciences shows that the same criteria do not always apply, nor do we always have all the data of the problem at hand. What we can argue, however, is that the number of anomalies is not as significant as their importance. More significant anomalies are those that affect the foundations of a Paradigm, its indispensable parts. Another key factor in diminishing the credibility of a Paradigm is the existence (or emergence) of an opposing Paradigm that manages to reconcile the anomalies.

The accumulation of anomalies leads to a state of crisis. The scientific community loses confidence in the Paradigm and begins again to question the foundations of the discipline. A period of dispute begins, during which various Paradigms, new and old, coexist and oppose each other. It is the—usually brief—period of idiosyncratic science, which Kuhn describes using a clearly political vocabulary. The Paradigm resembles a society undergoing a revolutionary period; its theories and methodological directives are institutions that fail to impose order; a period of anarchy follows, during which various social groups compete for power; critical argumentation progressively gives way to mass persuasion techniques; ultimately, power is won not by the more correct program but by the more persuasive one. Similarly, in the field of Science, the crisis period is resolved by the dominance of a new Paradigm. However, this dominance typically does not result exclusively from the explanatory completeness of the new Paradigm; the dialogue among scientists begins to resemble a dialogue of the deaf, and their final choice resembles more a “religious conversion” or a sudden change in visual perspective, as in the experiments of gestalt psychology (gestalt switches).… What was considered particularly radical or “heretical” in Kuhn’s view is the way the period of crisis is resolved, the nature of the scientific revolution. The change that occurs during a revolution cannot, for Kuhn, be reduced to a simple logical comparative assessment, a “reinterpretation of certain fixed and individual data.” Historical research shows that the introduction of a new Paradigm causes enormous communication problems among scientists. Scientists disagree about the scientific method, about the major current scientific problems, about the meaning of the terms they use (they speak different languages), they seem to live in different worlds. The Paradigms they embrace are incommensurable. Kuhn borrows this term from mathematics to emphasize that pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary science are not simply incompatible, but do not even have a common measure of comparison. We therefore cannot compare two successive Paradigms on an objective basis, nor can we make evaluative judgments about the correctness of each. All we can do is understand each Paradigm within its conceptual and sociological framework and assess how consistent it is with its principles and effective in the problems it sets out to solve.

Among other points, this was noted by Vassilis Kalfas, editor of the edition of Thomas Kuhn’s seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions published by “Sygchrona Themata” – the original English edition was published in 1962. Kuhn’s approach was itself a kind of revolution in the conception of the history of sciences (epistemology). And thanks to it, the complacent perception of specialists – that if there are periodically different “scientific Truths,” these ultimately represent nothing but the “progress toward perfection, toward absolute Truth” of the world, each one better than the previous – was thrown into the trash. On the contrary, through The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, not only was the real history of the imperfection of human thought restored, but also the internal, often conflictual intra-scientific reality behind the fog of the supposed sanctity and the alleged superiority of scientists and their claims.

Crisis (and) in cosmology?

Is astrophysics, and more specifically the Big Bang theory, in the state described by Kuhn sixty years ago for “paradigm shifts” in the sciences (especially in physics and all its extensions)? Exactly! And the cause is new observations, incompatible with the theory.

Scandal-machine is the James Webb space telescope. A project of collaboration between the American NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and its Canadian counterpart (CSA), the JWST (James Webb Space Telescope) is an ambitious program to extend (human) vision into space/universe much further than ever before. As it moves ever deeper into the unknown, its high-resolution and high-sensitivity devices send back to Earth images of “ancient cosmic objects” that were not accessible within the optical range of the previous endeavor, the Hubble Space Telescope. According to the aspirations of its creators, the JWST will allow the observation of the first stars and the formation of the first galaxies – the “first stars” and “first galaxies” which, according to the Big Bang theory, lie at the edge of the universe.

The JWST was launched on December 25, 2021, and its first image reached Earth on July 11, 2022. More continued to arrive, until just one week later, on July 19, 2022, 17 astrophysicists co-signed an article whose title began like this: Panic!

Panic!!! Indeed. The findings of the JWST did not agree at all with the predictions of the Big Bang: far too many galaxies, too “old”, too small, and too well-formed. This was not what was expected to exist “there” if this “ancient there” was according to the Big Bang the “far-away” of an ever-expanding / expanding universe. According to the first data processed by the authors of Panic!, the images of the JWST showed the existence of 10 times more galaxies than predicted by the Big Bang theory; and furthermore, very well-formed, with no indication of “merger” between them, again contrary to what the Big Bang theory predicted. To make things even worse, the galaxies detected by the JWST should have been 400 to 500 million years old (after the Big Bang). To great surprise, the age of some of their stars was determined to be over 1 billion years.

These data (data from the last 14 months) are added to other inconsistencies between theory and observations of recent years. According to physicist Eric Lerner1 the Big Bang theory so far counts 16 wrong predictions and only one correct one: the abundance of deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen, in the universe. These are the anomalies of a dominant scientific Paradigm according to Kuhn’s terminology, anomalies that accumulate.

Why, then, does the increasingly greater “instability” of Big Bang theory remain unknown and, to a large extent, still veiled even within astrophysical circles? Lerner presents his explanation, which encompasses all that Kuhn analyzed regarding scientific conservatism and guild behavior:2

… The answer lies in what I call “The Emperor’s New Clothes Syndrome.” At worst, one might say “I see the emperor’s elbow” or “I see the emperor’s knee,” perhaps even “I see the emperor’s butt.” However, it is forbidden to say “the emperor is naked.” Whoever questions the Big Bang is labeled foolish and unfit for astrophysics. Unfortunately, funding in this field comes from few governmental sources controlled by a handful of committees dominated by Big Bang theorists. These theorists have spent their lives building their careers on this theory. Whoever raises questions about it simply does not get funded.

Until a few years ago, if some researchers could self-fund a cosmological research, as is my case, they could publish their “heretical” views, although they were most likely to be ignored by the dominant view… But as the crisis in cosmology became evident in 2019, this dominant view began to entrench itself to defend itself through censorship, since it no longer had other defensive means. However, censorship is always harmful to science…

… Scientific questions, however, are stubborn and they are here. For decades, some scientists, starting with the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Hannes Alfven3, have shown that if the Big Bang hypothesis is abandoned, the evolution of the universe and the phenomena we observe today, such as the cosmic microwave background, can be explained using the physical processes we observe in the laboratory – especially the electromagnetic processes of plasma. Plasma is the partially ionized gas that makes up all the matter we see in space, in stars, and in the space between stars.

… One of the fundamental plasma processes identified by Alfven and his colleagues, a process that has been under study for 50 years, is the filamentation of plasma. This is the process by which electric currents and the magnetic fields they create pull plasma into the formation of dandelion-like systems of filaments which we see at all scales of the universe, from the aurora in Earth’s atmosphere to the solar corona, to the spiral arms of galaxies, even to clusters of galaxies. Together with gravitational forces, plasma filamentation is one of the fundamental processes of formation of planets, stars, galaxies and structures of the universe at all scales…

Lerner refers to what has been called plasma cosmology. This is a theory about the evolution of the universe which provides (or so claim those who support it) answers to the anomalies of the Big Bang theory without any of its basic assumptions. According to plasma cosmology, there is no “beginning of the universe” (nor end); there is no expansion-of-the-universe; there is no dark matter and dark energy.

We cannot of course check the reliability of plasma cosmology!!! We are (very distant) observers of the dispute around (human) cosmic theories, just as we are very distant observers of the universe itself. What interests us in this scientific field that extends so far from everyday experiences that it is considered exotic, and thus without the masses of fanatical followers of the dominant theory so far, is the noble character of what is called science.

Scientism

In 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 (and we reasonably assume henceforth) this doctrine – that it is a scientific matter (regarding mRNA genetic engineering platforms) – was imposed with two final decrees. This is a scientific issue – therefore it is not up for discussion by us, the “common mortals”… Or/and this is a scientific matter, therefore whatever the specialists tell (us) is correct. It is not at all strange that around the idea of science – taboo – opposing sides were found to coexist regarding the management of the “pandemic”, even the “pandemic” itself. On one side, the zealots of caradinieroi/pfizeroi and on the other, the preference for anti-caradinieroi but not anti-pfizeroi.

Even further back, criticism of biotechnologies and genetic engineering today hits a wall that did not exist 30 or 40 years ago: the mythologization of techno-sciences (not only these specific ones but all of them collectively…), which, even where it does not produce blind faith (a completely religious stance), dictates, imposes, and mystifies the notion of “entry forbidden to non-approved specialists.” What has changed between the 1960s and 1970s and the harsh (at the time) proletarian criticism-of-specialists, and the decades of the 2010s, 2020s, and beyond, with blind trust in specialists or/and awe toward techno-sciences?

The fundamental change is the multiplication since the 1980s of specializations, the mass multiplication of certified specialties through postgraduate studies, doctorates, seminars, etc.; in short, the continuous production of a mass body of citizens of modern western societies who are considered and consider themselves specialists in some sub-sub-subfield of some techno-science. The Establishment, in the 1960s, when these “certified scientists / specialists” were far fewer, spoke of specialized idiots. Given the realities of 21st-century capitalism, this involves not merely a massification of specialized ignorance (and therefore stupidity), but also the construction of a belief as massive as the (very large) volume of “graduates,” of “certified” individuals of all kinds within western societies: the belief in the sanctity of any compartmentalized, specialized knowledge. Hence, of the techno-sciences and the techno-scientists as a whole. We call this scientism: in other words, yet another ideology, at the dawn of the fourth industrial capitalist revolution.

Some have attributed to this situation, which seems unprecedented, the characteristics of religion. It has such (very much “faith”) but it is something much more mundane: the defense of real, symbolic (or imaginary) interests. And it is not even unprecedented. It is rather the “professional ideology” of scientists for the most part of the 20th century; in the excerpt from “Structure” that follows, Kuhn refers to exactly this: to faith.

Consequently, we can speak about the widespread diffusion within contemporary suburban and middle-class social relations, in contemporary representations and re-presentations of the Self – Capital, of the characteristics of the “possession of knowledge – capital / science,” which until the 1970s or even the 1980s were numerically limited. Characteristics of “professional ideology” that spread to millions of “graduates.”

See the excerpt below from Kuhn’s book4, written (we remind you) in 1962, when scientism was not yet a mass salvation plank:

…Let us accept, then, that crises are a necessary precondition for the emergence of new theories and let us now pose the question of how scientists react to these crises. An obvious but also significant part of the answer can be given if we observe what scientists NEVER do when they encounter even the most serious and persistent anomalies.

They may therefore begin to lose faith in it and subsequently examine some alternative solutions, but they do not deny the Paradigm that led them to crisis. In other words, they never regard anomalies as counterinstances—even though, in the terminology of epistemology, that is precisely what anomalies are. This assessment comes simply from historical facts… And it leads us to what will become clear when we examine the process of rejecting Paradigms: a scientific theory, once it acquires the status of a Paradigm, does not lose its validity except when there is an alternative Paradigm to take its place.

The historical study of scientific development has not revealed any process whatsoever that resembles the methodological stereotype of “falsification” after direct comparison with nature.

This observation does not mean that scientists do not reject theories, nor that experience and experiment are not essential points of such a rejection process. What it means, however – something that will prove to be a central point eventually – is that the decision-making process, which leads scientists to reject a theory previously accepted, never relies simply on a comparison between that theory and nature. The decision to reject a Paradigm always simultaneously involves the decision to accept another Paradigm; and the deliberation leading to this decision includes both the comparison of the two Paradigms with nature and the comparison of the Paradigms with each other…

Pay attention to these two things. First, if debunking is a possible but (difficult) acceptable situation within the so-called “scientific communities”, it is unbearable for individuals, the vast majority of whom are “experts” here or there, when scientism has become a social norm and a diffuse ideology. It has been observed and is being observed to excess over the last 3 years: supporters of all stages of the terror campaign feel that if they admit they were wrong, they will self-debunk themselves entirely as individuals! Even admitting that they were deceived, something very natural even 30 or 40 years ago, they consider to be something that undermines them, which they cannot tolerate…

And secondly, for the rejection of a (scientific) Paradigm, of a theory that is, it is not enough for it to contradict nature, even if this latter is the human body. It suffices for a branch of techno/science, genetic engineering, to kill and/or destroy the human natural immune system, the human body… Yet this, this harsh contradiction, for the supporters of scientism (who quite possibly may themselves be victims..) is not enough for them to reject this specific “scientific Truth” about life. Because this way their cosmoidol would shatter.

Astrophysicist Samuel Pearson commented on this: “These shouldn’t exist. It’s like throwing a cup of coffee into an empty room and having the coffee, after being spilled from the cup, all return back into it… And this happening not once but 42 times! There’s something wrong with the way we understand the formation of planets, or stars, or both.”

Science against scientism (;)

The theory of the Big Bang and any “cosmological crisis” is a painless case of (scientific) Paradigm Change. Painless in the sense that it does not affect the daily life of citizens; they can easily ignore it. In other fields, however, the side effects, both of any techno-scientific theories and of any discontinuities, contradictions, and inadequacies thereof, even of their malicious promotion and exploitation, are close at hand, immediate. There, the sanctity and unquestionability of “scientificity” becomes a weapon of domination.

Is there something that can be precisely defined as science, transcending the various historical (or social) determinations of the last 5 or 10 centuries of “Western” history? Historians of science themselves seem to answer “yes,” defining the line of distinction between “science” and “non-science” (whatever that latter might be) in relation to method rather than to conclusions, their applications, their successes and failures, discontinuities, or the duration of validity of the “truth” of this or that scientific theorem. However, such a definition (of the kind “science is experiment plus mathematics”) is highly debatable. Especially if one happens to observe fierce disagreements and arguments among “scientists” themselves. There, the category of “anti-scientific” is the mildest label that can be hurled among them; which means, at the very least, that what constitutes “science” has been relativized even among those who serve it.

As if these were not enough, and to make things even worse, the distinction between “science” and “technology” has almost disappeared. There are certainly strong links between them, and there always have been. But as “technology” (or, more correctly, certain fields of it) continuously produces more and more machines/devices for everyday use, shaping what some have called the technological ecosystem, it also constructs the representations of the “general public”; ideology, more correctly.

For technology, the prevailing idea is practical. It works: machines “work” (or break down). For science, the prevailing idea is much more philosophical. It is the truth. The “truth of the world,” to a sufficient (though not always acknowledged) extent the “immutable truth of how ‘it is’ (that is: how ‘it works’) in the world.” Although many (and Mr. Trachanas among them…) claim that the distinctive element of anything that can be called science is the experiment (and along with it the verification or falsification of a specific hypothesis or theory), in our opinion the main characteristic is something else. It is the secularization of the “laws (of nature).” That is, the ability of the human mind to conceive / understand / analyze / translate them; in contrast to the religious notion that such “laws” do exist (and indeed very strict ones), but that they are known only to some god, hence inaccessible to human understanding.

The commonplace idea, then, of the natural law (from the “law of gravity” to…) and therefore of the inherent Truth (with a capital “T”) of every natural law, which is or can be understood by a small subset of this “nature” (the human species…), an idea that constitutes a secularization of another, the idea of the “world-creating god” and sole knower of the “laws”, is that which inspires but also haunts scientists. At the heart of any scientific inquiry, theory, method, the ghost of a great clockwork mechanism lurks; it matters not whether the gears have been sought in Mendel’s “laws of heredity,” Kepler’s “laws,” the “laws of quantum mechanics” of the Copenhagen interpretation, or now in the “laws of quantum entanglement.”

We are therefore entitled to have the following question: if any “body of knowledge” defines its own ways, its “internal rules”, its “internal processes of verification and/or falsification,” is it automatically entitled to be immune to any external criticism? Christian religious faith claimed, at its best, that it constitutes the only valid form of knowledge, let’s say “knowledge through revelation.” It had shaped not only the “internal rules” of the “path to divine illumination,” but also institutions/mechanisms of “verification and/or falsification”: for example, episcopal synods (a kind of conferences…) where “heretics” were often anathematized – that is, the “false believers,” the “deceived,” the “instruments of Satan.” Certainly, experimentation was not generally included in the repertoire of seeking divine illumination; but this did not make the church hierarchy less certain that it knew or was close to the “divine will” or the divine order of the world.

However (and the history of science is a witness) even experimental scientists (various, indeed, particularly famous ones) lived and died with the certainty that they knew at least one of the fundamental – laws – of – nature; only for a (initially “heretical”) new scientific truth to come along later and contradict them. Until it too is contradicted by a subsequent one.

As a collective adventure of human thought, these successive waves of discovering “laws of nature” and then disproving them—which dismantle whatever might be called science—are particularly interesting, even entertaining, at least up to a certain point. When it comes to the oath concerning the revelation of Truth, of the immutable and unquestionable Truth-of-the-World, science is a collection of failures, no less than various religious collections. And perhaps here lies a pure (though unacknowledged) reason why, from a certain point in time onward (let’s say: in the wake of the 20th century), even “learned scientists” become increasingly openly metaphysical, often of the worst kind. It is highly probable that there exists a fundamental (intellectual) error in the belief (for it is indeed about belief) in the existence of a single, immutable, and unquestionable Truth (with a capital “T”) about the World. And if this is so, then this error is equally shared by scientists and theologians; which means they might be closer to each other than they themselves acknowledge. In the end, scientists are no longer justified by the joy of the adventure of thought, but by the applications they produce. By technology, that is.

The spread (perhaps even the imposition) of scientism and, ultimately, the profound alteration of what science is, could be considered synonymous with technocracy. Science is not “faith in an immutable Truth” (with a capital T) – that is religion, which of course flourishes even within various “scientific circles.” Science is verification, documentation, but also criticism, evidenced questioning.

Scientism is the undermining of justified doubt, the prohibition of criticism in the name of, precisely, the sanctity of Truth, which appears as unshakeable because it is based on something that has been named “natural law.” It is produced from many sides. From the entrenched interests (economic, reputational, etc.) of those who serve a given (scientific) truth when it begins to be strained under the weight of its accumulating anomalies… From the interests of entrepreneurs who trade in the applications of this or that (scientific) truth… From the fears and insecurities of subjugated populations, who need certainties even if they are mythological… From the arrogance of all those (as Egos – Capitals) who have to display the certification of a specialized knowledge, even if it is of no social value, even if it is antisocial.

Is it possible for science to turn against scientism? If someone imagines such a thing as a collective self-criticism and self-purification of scientists and the societies of the 21st capitalist century, they are simply wasting their time. The only possibility would be for science (the sciences…) to escape from economic control (the bosses) and the ideology of social superiority (the scientist). The only possibility would be for critical scientific knowledge to leave the hands of incorporated specialists, the technocrats of the system. We would dare to say only the workers’ alienation of science could free it from the tyranny that it itself supports.

But if this is so, with today’s conditions, we are wasting our time…

Ziggy Stardust

- Quite active today, the 76-year-old Lerner has a long history of participating in banned political actions in the US: in 1968 he participated in student mobilizations at Columbia University against the war in Vietnam; and in 2011 in the Occupy Wall Street movement… ↩︎

- The Big Bang didn’t happen, August 11, 2022. ↩︎

- The Swedish Hannes Olof Gosta Alfven (1908 – 1995), physicist and electrical engineer, won the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research in magnetohydrodynamics. Magnetohydrodynamic waves are named after him as “Alfven waves”. Among other things, plasma physics, in the development of which he had significant contribution (it is considered), plays an important role in the creation of galaxies. ↩︎

- The reaction to the crisis, p. 150, etc. ↩︎