Machines that perform calculations with complex algorithms, based on large amounts of data and extract smart-looking answers, are not only fed by the fragmented knowledge of their creators, but also by other materials. Such as electricity, our data, and… water. According to a report1 published in April 2023, “ChatGPT requires a 500 ml bottle of water for a simple conversation with approximately 20-50 questions and answers.” More specifically, the report states:

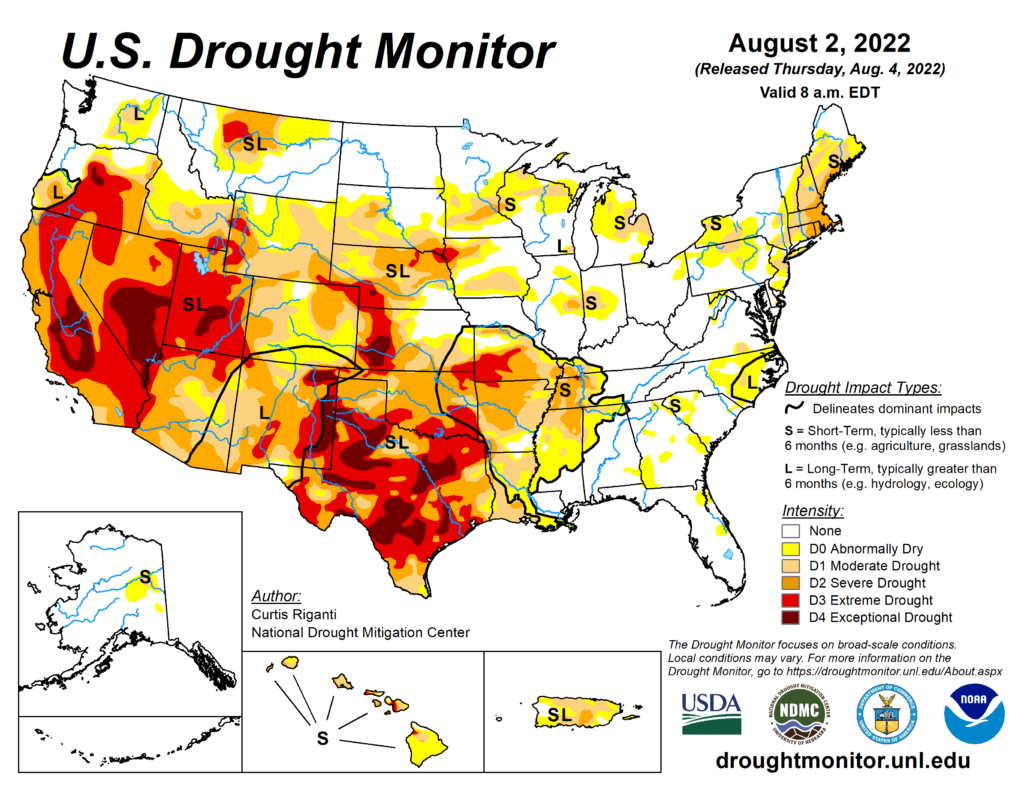

Despite the water cycle through our planet’s natural ecosystem, available and suitable clean water for use is extremely limited and unevenly distributed throughout the world. Severe water scarcity already affects 4 billion people, or about two-thirds of the global population, for at least one month each year.

The massive data centers, the “homes” where the majority of artificial intelligence models are trained and developed, are known to be energy-intensive, collectively representing 2% of global electricity, as well as a large carbon footprint. However, what is much less known is that they are also extremely “thirsty” and consume vast amounts of clean water. For example, Google’s own data centers in the US consumed 12.7 billion liters of fresh water for cooling in 2021, about 90% of which was drinking water. This staggering amount of water is enough to produce 6.9 million BMW cars or 5.7 million electric vehicles (including battery cell manufacturing) from Tesla, according to water consumption data published by BMW and Tesla. The combined water footprint of US data centers overall in 2014 was calculated at 62.6 billion liters.

These enormous quantities of water, which are mainly clean/potable water, are used to cool the machines in data centers where, apart from “artificial intelligence”, all the other applications we use (or not) daily are also “running”. The above report focuses on “artificial intelligence” as the machines and computations required for it are more “heavy”. However, the reality is not much different without it either. Electric vehicles, for example, mentioned above would be useless without the existence of digital systems and consequently data centers, which will provide the user (less) and the owner (more) with all these digital services they promise. Thus, these promises end up in the exploitation of water – and many other natural resources – even where there is scarcity, such as in Uruguay last summer, where during a water shortage Google’s data centers were supplied with fresh/potable water while homes received filtered seawater.

It would be redundant to defend water for water’s sake. Generally, nature does not need us. We need it. But the issue now is how it needs it, and the new paradigm, that of “digital transition” and “green growth.” And it needs it much more compared to the previous one, since its material prerequisites are more demanding in natural resources. The text we translate below documents this to a certain extent; that is, how what is being portrayed as a “green transition” and “critique of the old polluting model” is nothing but another myth of the dominant narrative.

Wintermute

Capitalism and environmentalism. The (non-) ecological transition2

From the extraction of raw materials to final recycling, the green narrative is full of omissions: environmental destruction, water waste, pollution, exploitation, energy consumption by Big Tech. The latest capitalist technological revolution has nothing to do with environmentalism.

Let’s take the case of wind turbines: the development of this market will require, from now until 2050, 3.2 billion tons of steel, 310 million tons of aluminum and 40 million tons of copper, as wind turbines will need more raw materials than previous technologies. For the same capacity [electricity generation], wind infrastructure will require up to fifteen times more concrete, ninety times more aluminum and fifty times more iron, copper and glass than facilities using traditional fuels.

O. Vidal, B. Goffe and N. Arndt, Metals for a Low-Carbon Society, Nature Geoscience, vol. 6 November 2013

The exhibition clearly shows that the technologies that are supposed to complement the shift towards clean energy – wind, solar, hydrogen and electric – require significantly more material resources for their synthesis than today’s traditional energy supply systems based on fossil fuels.

World Bank, The growing role of minerals and metals for a low carbon future, June 2017

8.5 tons of ore must be cleaned to produce one kilo of vanadium, 16 tons for one kilo of gallium, 50 tons for the equivalent of gallium and 200 tons for an insignificant kilo of an even rarer metal, lutetium.

Guillaume Pitron, The War of Rare Metals, Luiss Press, 2019

Ecological and digital transition: a phrase that has become an urgent necessity, a slogan that no one questions anymore. Rarely have we witnessed a paradigm shift with such speed: from a topic discussed by minority groups and for specific issues, within just a few months environmentalism was transformed into a dominant thought. As is known, the turning point was 2018 and Greta Thunberg.

There is no need to promote conspiracy theories, simple logic suffices: each of us knows that we can sit outside our country’s parliament for months without any coverage in the media, nor an invitation to speak at the UN assembly and the annual Davos forum, if the issue we promote does not intersect with the interests of an economic sector that is already hegemonic or is striving to become such within the capitalist field of power. As Gramsci teaches, hegemony is based on consensus: it is “moral and intellectual leadership”, it is an educational relationship based on the recognition of legitimacy by the masses. And the creation of this consensus was the task that the emerging “green industry”, supported by the technology industry, assigned to the little girl with the braids.

An innocent, pure, passionate figure and image, probably good at faith, perfect to be transformed into a symbol within a narrative built to draw strength from the characteristic of its generation: teenagers who demand accountability from the adults of the world. Many countries were on the path of ignoring the Paris agreements of 2015, amid general indifference. Greta Thunberg and what the Frankfurt School defined as the “cultural industry” created the Fridays for Future, with thousands of children taking to the streets “for a better world” and, within a few months, the leadership was confirmed: the issue of climate change and the energy transition has been established at global tables and in December 2019 the EU Commission also began talking about the “European Green Deal”.

The problem of climate change and environmental destruction in general does exist, therefore the attention ecology finally received is positive. However, the narrative that emerges is guiltily partial, and could not be otherwise since it is influenced by the capitalist interests that manipulate it. The so-called “clean” energies actually involve the use of “dirty” minerals whose exploitation is anything but clean. The so-called “renewable” energies are based on the exploitation of raw materials that are not renewable. Finally, the green and digital transition has now become, for capitalism, an inevitable and necessary step – although painful for certain industrial sectors – which will bring along geopolitical changes.

Not clean and not renewable

The starting point that we must not forget is that the ecological transition cannot be achieved without the digital one. This involves so-called “smart grids,” structured with artificial intelligence software, which will be able to regulate the flow of electricity in homes and industries based on their needs. They will be weather forecasting algorithms that will improve the performance of photovoltaic panels. They are digital sensors that will be able to adjust the intensity of street lighting based on traffic, while “rare earth magnets” are the essential component of electric cars, wind turbines, photovoltaic panels, and all digital technologies. Magnets that made possible a significant reduction in the weight and size of objects compared to those made from ferrite: with the same power, the former are a hundred times smaller than the latter. These are the magnets that allowed electric motors to compete with thermal ones, while rare earths, with their catalytic, optical, and magnetic properties, are introduced as irreplaceable elements in smartphones, computers, screens of all types, robotics (including military), low-energy light bulbs, semiconductors, industrial materials (to make them lighter and more durable), solar collectors, wind turbines, electric car batteries, etc. Electromagnetism is the power energy of the green transition, and rare earths are the raw material of the ecological and digital future.

Guillaume Pitron’s book, The War of Rare Metals (Luiss Press, 2019), rich in sources, notes, bibliography and appendices, is the appropriate text to start moving in this world. There are about thirty rare metals3, while there are 17 rare earth elements4. Despite their name, they are relatively abundant in the earth’s crust, but their extractable concentration is not so high. Therefore, the mining and purification process is lengthy and extremely polluting and uses huge amounts of water. It starts with crushing the rocks and then proceeds to use chemical reagents such as sulfuric and nitric acid, steps that are repeated dozens of times. At the end of the refining process, hundreds of cubic meters of water remain loaded with acids and heavy metals that pollute the soil and aquifers. Mining is not even free of radioactivity. Not because of the rare earths themselves, but because of certain minerals (such as thorium or uranium) which are used in the following separation process: the radioactivity rate is weak according to the tables of the International Atomic Energy Agency, but they are waste that must be stored safely for hundreds of years.

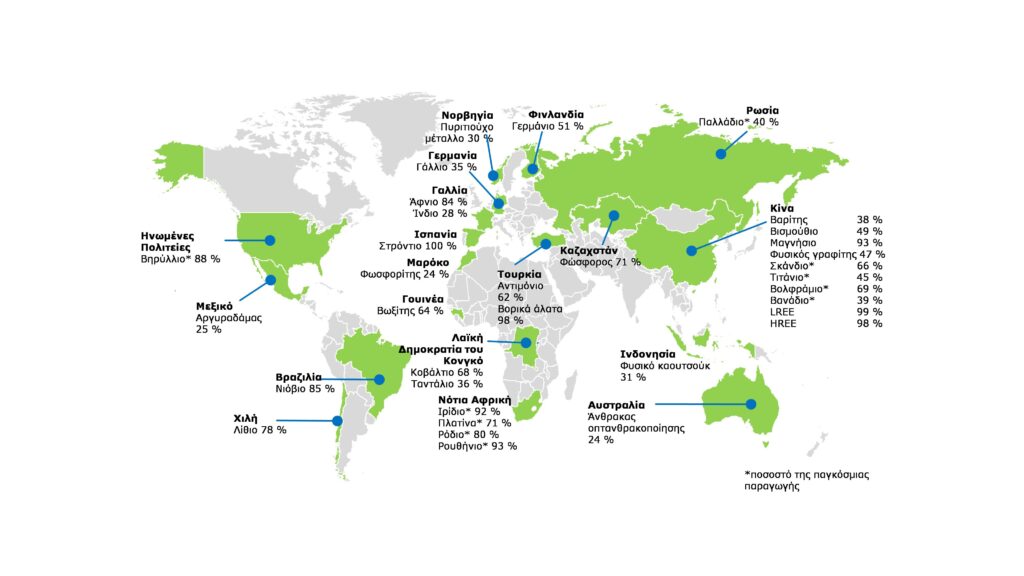

In fact, it is not coincidental that the main mines are located in the Third World or in developing countries. The energy and digital transition, as it has been structured, is a “transition for the richest classes,” Pitron rightly emphasizes. France and the United States, for example, had significant deposits and industries. The Mountain Pass mine in the U.S. dominated the rare earth market until 1985, only to close in 2002 due to ongoing environmental damage and subsequent legal cases. It reopened in 2012 but declared bankruptcy in 2014, unable to compete with the Chinese market that had emerged in the meantime. Since 2018, it has been trying again: the U.S. goal to reduce its dependence on China for a currently strategic resource has resulted in pollution problems. In the 1980s, the French group Rhône-Poulenc refined 50% of the global rare earth market: radioactivity was present everywhere. Under pressure from NGOs and local committees, in the mid-1990s it abandoned the most polluting part of the production process, purchasing partially purified minerals from China. Subsequently, the West outsourced the environmental destruction and pollution to external partners, and today China covers 95% of the world’s rare earth needs.

Paradoxically, mining an ore—and this applies not only to rare earths but to all metals necessary for green infrastructure—is also a high-energy-intensity activity, or, to use the language of ecological transition, one with “high greenhouse gas emissions.” And it will increasingly be so. Because rising demand will be met by exploiting even the less profitable deposits—as has already happened with oil. “Some experts say that confirmed reserves of rare minerals are smaller than what actually exists, since there are still deposits yet to be discovered,” says Pitron, citing chemist Ugo Bardi, “and therefore there would be no reason to worry about the risk of shortage. However, the production of these metals accounts for between 7 and 8% of global energy.” What would happen if this proportion rose to 20–30% or higher? According to Bardi, in Chile the energy required for copper mining increased by 50% between 2001 and 2010, while total copper production rose by only 14%. Thus, the limits to mining are related to energy, not quantity.

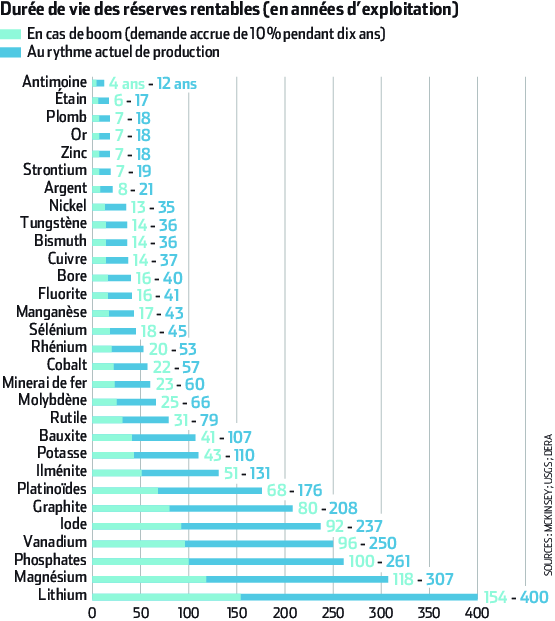

However, they are undoubtedly finite resources, and we are already beginning to talk about shortages: at the current rate of production, the profitable reserves of about fifteen basic and rare metals will be exhausted in less than fifty years. Even earlier if demand increases. And demand will increase.

Limiting our gaze only to the European reality, the EU Commission wrote in its 2020 three-year report on the resilience of critical raw materials: “For electric vehicle batteries and energy storage, the EU would need up to 18 times more lithium and up to 5 times more cobalt than the current supply of the entire economy by 2030, and 60 times more lithium and 15 times more cobalt by 2050. If not addressed, this increase in demand could cause supply problems. The demand for rare earths used in permanent magnets, for example in electric vehicles, digital technologies or wind turbines, could increase tenfold by 2050”5.

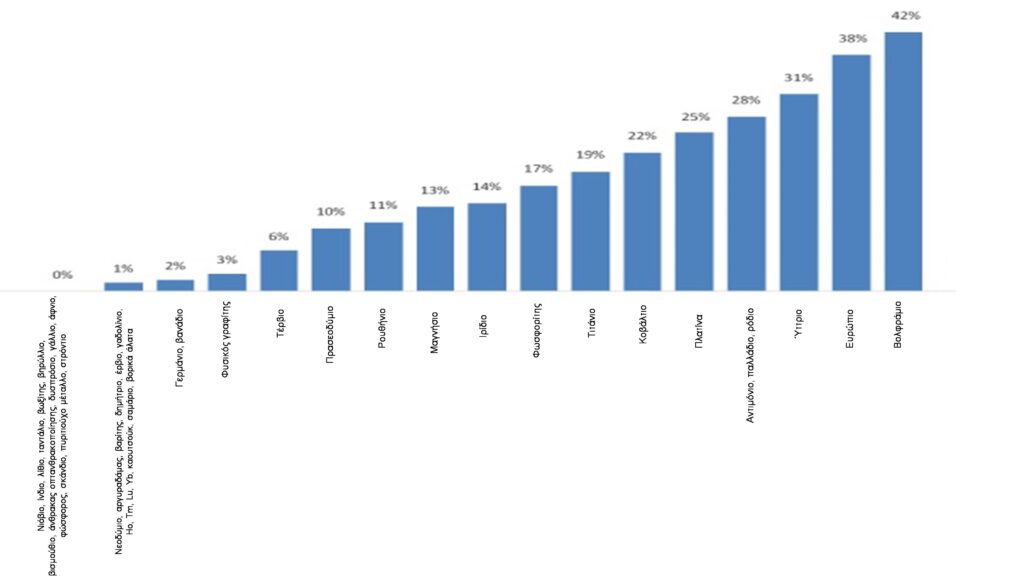

Until today, recycling has also been excluded. Techniques have been found to accomplish this, but they are slow and very complex processes – rare earths do not enter their pure state in the construction of technological devices but in the form of alloys – economically unprofitable ones that, in turn, use other chemical products. The European Commission also emphasizes this in the report mentioned above: “The EU is at the forefront in the field of circular economy and has already increased the use of secondary raw materials. For example, more than 50% of certain metals such as iron, zinc or platinum are recycled and cover more than 25% of consumption in the EU. However, in the case of other raw materials, especially those used in renewable energy technologies or in high-tech applications, such as rare earths, gallium or indium, secondary production represents only a marginal contribution.

Finally, but no less important, is the aspect of human exploitation and health damage. Every so often, photographs emerge, only to disappear the next day—even in the mainstream media, the champions of ecological and digital transition—of children at work, earning starvation wages, submerged up to their torsos in contaminated mine water or toxic waste. As early as 2016, the annual report by Pure Earth and Green Cross Switzerland ranked the top ten most polluting industries based on the health damage they cause to people: first is the recycling of used lead-acid batteries (used in vehicles), and second is mining and mineral processing6.

Even for electric cars, the flag of the green transition, the ecological balance of the vehicle’s entire life cycle is still uncertain. Among positive and other negative studies, what everyone agrees on is that their production – from the mineral extraction phase, to industrial manufacturing, to final disposal – has a worse environmental impact than the production of internal combustion engine vehicles, especially due to lithium batteries (generally only CO2 emissions are counted and not water waste, soil and groundwater pollution, deforestation, radioactivity, destruction of biodiversity and ecosystems, etc.) When the analysis proceeds to the use of the vehicle, the scenarios are different, because what has a strong impact is the energy mix that will be used for charging, between renewable energy sources and fossil fuels.

“In simple terms,” concludes the World Bank study referenced at the beginning of the article7, “the future of green technologies (wind, solar, hydrogen, and electric) has high material mining intensity, and if not properly managed, it could undermine countries’ efforts and policies to achieve climate goals and related sustainable development targets. Furthermore, it potentially has significant impacts on local ecosystems, water systems, and communities.”

To the green technologies are added the material and energy needs of the digital world: the “cloud”, virtual reality, the internet… The big technology companies do whatever they can to sell a floating and bodiless image (the cloud…) inherently friendly to the environment, while rare earths constitute essential and irreplaceable raw materials for technology and its entire infrastructure is radically material: satellites, rockets for their launch, computers that regulate their trajectory and information transmission, submarine cables, aerial and underground electrical networks, huge and numerous data centers and finally the tablets, computers and smartphones we all have in our hands and which we must constantly recharge. A “megamachine” that devours energy – and water, necessary for the cooling systems of data centers.

According to a 2018 study8, “the energy consumption of computers, data centers, network equipment and other ICT devices9 (excluding smartphones) has reached 8% of total global consumption and is expected to reach 14% by 2020. What is even more surprising is that these figures and projections do not include the manufacturing phase, especially in light of the fact that ICT devices have a much shorter useful life (2-5 years) than any other hardware component.” In reality, the designed “obsolescence” (the fact that devices become obsolete very quickly) feeds the production process, from mining to the final product. The analysis predicts that by 2040 the technology sector will represent 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions, which is equivalent to “more than half of the current contribution of the entire transportation sector.”

According to a 2019 report10, “the energy consumption of ICT is increasing by 9% every year. The digital transition, as it is currently being implemented, contributes more to global warming than to preventing it.” Again, in the same report: “The share of ICT in global greenhouse gas emissions has increased by half since 2013, from 2.5% to 3.7%. The gradual appropriation of a disproportionate share of available electrical energy increases the intensity of its production, which is already struggling to be freed from carbon.”

Conclusively, what the narrative of ecological and digital transition lacks in order to be presented as environmentally improved is the overall view of the industrial cycle, from the extraction of raw materials to final recycling, which passes through the construction of technologies and overall energy needs.

It’s just capitalism, baby!

From coal with the steam engine, to oil with the thermal engine, to rare earths and digital technology, capitalism is on its way. It was always the cutting-edge technology that guided and marked the phases of the industrial revolution. It is not a choice, it is an inherent dynamic of the system: scientific progress – which is funded by private capital in order to direct it towards its own interests – creates new markets and new opportunities for profit (abundant profits, as initially oligopolistic), creates renewal of production and goods – new systems and new objects – creates new induced desires for consumer society and new dominant ideologies to be transformed into consensus of the dominated, in order to feed the society of the spectacle. Without technical renewal capitalism would not survive. Digital technology is the new “steam engine” and rare earths are its energy source. And as in previous transitions, there are punished capitalist sectors that will disappear – and which are now struggling to resist as much as possible – and companies that will close if they do not find the time to update; but this is the rule of the game.

Within the field of capitalist power, there is always the dominant sector: it is the axis of the industrial revolution that marks the phase, therefore it is historically determined and as a peak it has the closest relationship with political and military power. Today the digital sector dominates, which not only has permeated all sectors of production, from industry to services, but, since it connects with “green growth”, it has promoted its rise through public money – NRRP, European Green Deal, funding related to the transition, etc.

The symbol with the braids, therefore, could only promote a partial narrative of the green and digital transition, in which the non-clean and non-renewable aspects are omitted. In reality, it is at least naive to believe that the multinational corporations that are the queens of capitalization on the stock market, of labor exploitation, of life and data utilization, suddenly take into account the environmental fate of the planet and consequently of the global population. It’s simply capitalism, baby!

Disagreement

Without wanting to open any geopolitical analysis – which would deserve a much more detailed analysis – certain aspects are obvious. Every technological revolution corresponds to a new source of energy, which is equivalent to a new cycle of global hegemony: Great Britain with coal, the United States with oil, China with rare earths.

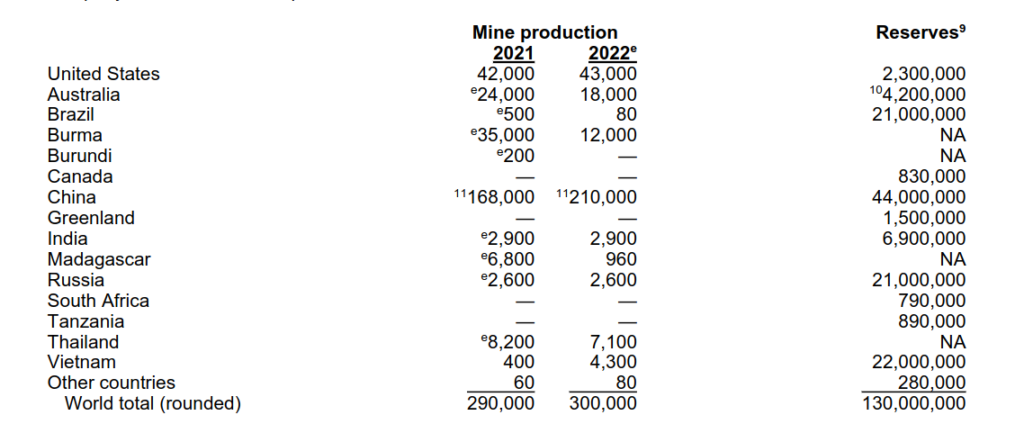

For Western countries, the digital industry—the engine of the current capitalist revolution—operates under U.S. leadership, but its supply chain’s hearth is in the Celestial Empire, which has nearly reached the strength and capability to aspire to wrest global hegemony from the United States. It will still take time—especially for the dollar to be displaced as the world’s reference currency. The U.S. and the European Union are well aware of the critical situation. The former carefully monitors global production and reserves of rare earths, as reported annually by the government’s National Minerals Information Center11. The latter monitors their dependence on “critical raw materials,” defined as “the most economically significant and presenting a high supply risk.” Access to these materials is, in fact, “a matter of strategic security for Europe’s ambition to achieve the Green Deal”12.

Minerals and rare earths are finite resources. The risk of shortages is already being taken into account in medium-term/long-term analyses. Short-term, history teaches, “shortage” means stockpiling – that is, export restrictions: China has already threatened them and has partially applied them – price speculation and wars for control of resources. We are facing a phase of conflicts, increasing geopolitical tensions – from which the war in Ukraine was also triggered – increasing inequality and poverty.

Climate change affects the planet and our lives. Is it the ecological and digital transition, aimed at reducing atmospheric pollution, the lesser evil at present? If so, we should at least be aware that it entails a high level of environmental destruction. And, above all, we must understand that an economic system that pursues unlimited profit accumulation, and therefore infinite production of goods and induced needs, a consumerism based on exchange value, and a society that has forgotten the value of use, is incompatible with our existence on a finite planet. We can also embark on a new Space Race, and this is what Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Larry Page, and Big Tech in general are doing: a hunt for new mineral exploitations and plans for space colonies. The solution will certainly not be found there—unless we want to sacrifice thousands or millions of human lives and abandon the fight against poverty and inequality—but only if we go to the root of the problem: capitalism.

Translation: Wintermute

- Making AI Less “Thirsty”: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models. Available here. ↩︎

- Capitalism and environmentalism. The (non) ecological transition – Paginauno Magazine, June 2022 ↩︎

- The European Commission has drawn up a list of these rare metals, defining them as “critical raw materials.” They are the following: antimony, barite, beryllium, bismuth, borate, cobalt, coke, fluorspar, gallium, germanium, helium, indium, magnesium, natural graphite, natural rubber, niobium, phosphorite, phosphorus, silicon metal, talc, tantalum, vanadium, platinum group metals, platinum group metals, heavy rare earths and light rare earths. ↩︎

- Rare earths: lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, lutetium, scandium, yttrium. ↩︎

- European Commission, Resilience to critical raw materials: Mapping the path towards greater security and sustainability. Available in Greek here. ↩︎

- The Toxics Beneath Our Feet – Green Cross Switzerland, Pure Earth – 2016. Available here. ↩︎

- The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future – World Bank 2017 ↩︎

- Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations. Available here. ↩︎

- ICT: Information and Communication Technologies. ↩︎

- Lean ICT: Towards digital sobriety – The Shift project. Available here. ↩︎

- Rare Earths Statistics and Information ↩︎

- As before, in the European Commission’s proposal in footnote 3. ↩︎