We copy from a random article, from the first results of the search engine, searching for the term “new genomic techniques”:

New genetic techniques (NGTs), or gene editing techniques, are methods for creating targeted mutations (mutagenesis) in the genome of living organisms. An example is the “genetic scissors” known as CRISPR/Cas9, which was introduced in 2012 and allows precise DNA editing at the level of individual bases (individual units or “letters” of the genetic code). While the resulting plant or animal derived from NGTs is not always distinguishable from conventionally bred organisms, NGTs are much faster than traditional methods for reproducing plants or animals with desired traits (e.g., crossbreeding). The precise editing by NGTs allows rapid results within a few generations. In contrast, conventional breeding techniques may lead to unwanted or unintended off-target mutations, which then need to be removed.

A “genetically modified organism” (GMO) can be a plant, an animal or a microorganism whose genetic composition has been modified using biotechnology, usually by transplanting genes encoding the desired characteristics from one species to another. This differs from NGTs, which are used to process an organism’s existing genes in a highly targeted manner and without introducing foreign genetic material.

Using conventional breeding methods, it may take 10 to 15 years until a new (plant) variety is ready for the market. Due to their precision, NGTs are much faster and allow farmers to quickly adapt to changing conditions. As climate change causes extreme weather events and the spread of plant diseases, NGTs become valuable tools for adapting agricultural production and achieving food security, providing speed and flexibility to the breeding process. Additionally, crops derived from NGTs can exhibit increased yields and reduced need for pesticides, leading not only to better incomes for farmers but also to more sustainable food production.

Generally, there is no scientific evidence to prove that NGTs involve higher risks than any other reproductive technology. Changes in genetic composition occur naturally between generations of plants and animals. Given that NGTs produce very specific mutations in plant genomes that naturally occur during evolution, the health impacts from foods derived from NGTs are unlikely.

In 2018, the EU Court of Justice ruled that NGT products are classified as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and must be treated in accordance with the strict European legislation on GMOs. Given that the regulatory framework is very time-consuming and costly, only a few large companies have the resources to work on NGTs and their approval. The European Commission’s proposal on how to legislatively regulate products derived from NGTs is expected to be published in July 2023.

Indeed, in the summer of 2023, the proposal to deregulate “new genomic techniques” reached the European Commission, which essentially means the abolition of safety controls and labeling on products indicating that they are genetically modified, since, according to the proposal, organisms that have undergone up to 20 mutations can be characterized as natural. These belong to the NBT-1 category, while those with more than 20 mutations fall into the NBT-2 category and thus will be required to undergo checks. Of course, the number “20” is arbitrary and appears aimed at creating a false impression that there is a limit. In reality, it is exactly the opposite—the abolition of limits on anything that can be created in the laboratory (and patented, obviously…).

There is no serious study confirming the safety of the number “20,” nor of anything else mentioned in the above excerpt. What exists is the muddying of waters with wordplay: “faster,” “more targeted,” “without introducing foreign genetic material,” “climate crisis,” “sustainability,” “conventional reproduction techniques may lead to unwanted or unplanned off-target mutations,” “there is no scientific evidence proving that NGTs involve higher risks than any other reproduction technology.”

On the contrary, there are studies and reports that document the “new” risks (of NGTs), which do not differ much from the “old” ones (of GMOs), since the basic idea in both, the method by which they approach the issue of reproduction/cultivation of organisms, is the same: bypassing natural evolution (and natural mutation). More targeted now? Yes, but the targeting they refer to has to do with the fact that these new techniques “tamper” with the genome at more “specific points” – something like a scalpel compared to the “old sledgehammer” – and this has nothing to do with safety in relation to the emergence of side effects in the organism itself and its environment. Without introducing foreign genetic material? Perhaps, but this is completely irrelevant, since damage can be done even when genetic material from the same family is introduced. Without “undesired or unintended off-target mutations”? By no means, since it has been proven that CRISPR/Cas9, the so-called “gene scissors”, can accidentally “cut” at unrelated sites. There is no evidence showing that NGTs have higher risks than GMOs? Perhaps, but rather this is due to the fact that there is evidence that they have at least the same risks.

Jack Heinemann, professor of biology at the University of Canterbury, notes that it is this “language of industry” that manipulates people into accepting the deregulation of new GMOs, and that deregulation is in reality simply a way to eliminate labeling and people’s freedom to choose non-GMO.

Regarding the argument “mutations also occur in nature” in favor of GMOs, he says: “The fission of the radioactive element uranium can also occur in nature (albeit rarely), but a nuclear bomb explosion massively scales up the process, and with this escalation comes a much greater risk. Therefore, it is clear that we should not deregulate the construction and use of nuclear bombs. It is the scaling up that increases the risks. In nature, birds and insects fly, but this is no reason to release commercial aircraft. You can divide any technology into sufficiently small pieces and claim that each piece can occur in nature. This is the justification used to promote the deregulation of genetic technologies.”

Regarding whether the new GMOs can be detected, he said “of course detection is possible, otherwise the industry would not be able to enforce its patents. But deregulation will allow companies to keep the detection method secret, while until now in the EU, a detection method must be published for each GMO as a condition of approval.”

He also points out that “with natural reproduction, the chances of damage are small, because the time frame within which interventions in reproduction take place is quite large, allowing us to adapt. With gene technologies, our intervention in the genome escalates, since there is the possibility for billions of GMOs to be released simultaneously, and natural suppression mechanisms, in a healthy ecosystem, could not control this damage.”

Professors, scientists and organizations, with the same and more arguments exist many. Nevertheless, the proposal came in the summer of 2023 and while there was no majority “for” in the council of agriculture ministers of the EU in December 2023, it was voted “for” in the European Parliament’s environment committee on January 24, 2024.

The European Parliament subsequently, on February 7, 2024, also voted “for” but partially. It approved the production of these “new” GMOs, without requiring industries to provide proof that they are harmless. Moreover, with the same decision, traders and farmers are exempted from any liability if any kind of damage is caused to anyone; people or nature. And still the member states of the EU will not have the right to unilaterally reject such a directive, refusing the cultivation or trade of the “new” GMOs.

On the other hand (not by a large majority) it decided that these products must have special labeling on their packaging – something that greatly annoys all “friends of GMOs”, since they understand that if these products are distinguished in the market (on shelves, etc.) it is very likely if not certain that they will be rejected by consumers.

The not “absolute victory” of biotech companies will force the Commission (which promotes this legislation along with the non-labeling…) and the lobbies to start a new round of “consumption” towards European deputies to convince (or buy…) as many as needed in a subsequent “plan” that will make the necessary adjustments.

But an additional problem has emerged: not all EU member states agree on this “liberalization”. This matters because if the Commission’s and companies’ proposal is finally approved (with one or the other content) they will not be able to ban the modified crops on their territory.

The two texts we translate below refer to two points that are important to clarify in every case. First, what are the (new and old) technologies of genetic modification of organisms and how do they differ from mutations that occur in nature or are the result of conventional crops? Does the rhetoric that “these things happen in nature too” have some basis, or is it yet another (criminal) distortion of reality? And second, are the pure intentions of states, industry, and “civil society” for the problems of the planet and humanity what drive them to find solutions with science as their weapon? Or is it the (repeated) arming of science (against us) in order to satisfy specific interests?

Wintermute

What (not) is genetic engineering1

In 2012, the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas technology led to a new boom in genetic engineering. This happened because the new techniques—known as “genome editing”—allowed intervention in the genetic code in an entirely new way. Since then, many stakeholders—both scientists and entrepreneurs—have seen a new opportunity to make genetic engineering socially acceptable in European agriculture. In the past, it was met with widespread condemnation. Even now, virtually no genetically modified crops are grown in Europe2. Those interested had long wanted to change this. Therefore, with the discovery of the new methods, they made sure to use the appropriate “framing” to create the desired context for the technology: no longer is it referred to as “genetic engineering.” Instead, the new techniques are called “precision breeding” or simply “new breeding techniques.” The argument put forward is that these new technologies can be applied without introducing new genes, and the changes (mutations) cannot be distinguished from natural ones. Therefore, it is not genetic engineering. Is this true? Are conventional breeding and the new genetic engineering techniques the same thing? What are the differences and what are the risks?

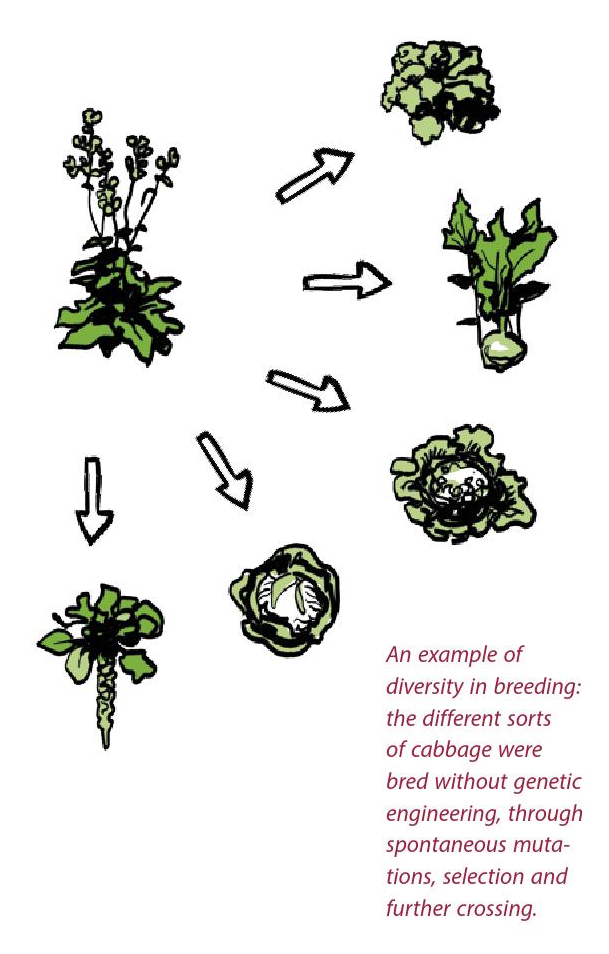

Conventional breeding3 has been used for thousands of years to improve crops and livestock. It uses the mechanisms and processes of (natural) evolution, where new varieties arise, particularly, from further crossbreeding and selection.

Various “tricks” can be used to induce these mutations and increase genetic diversity; for example, plants can be exposed to chemical substances to accelerate evolutionary processes. Subsequently, new mutations and new traits emerge. At this stage, it is not possible to predict where changes, i.e., mutations in the genome, will occur. However, it is not entirely random either. Changes occur based on the natural rules of heredity and gene regulation. (Natural) evolution has developed many different mechanisms to protect species preservation while allowing these changes. These include, among others, cellular repair processes and the creation of “backup copies.” The interdependencies between plant genes and their interactions with the environment are processes that have been developing and “validated” for millions of years. Conventional breeding always uses whole plant and animal cells that have emerged from (natural) evolutionary processes. It does not directly intervene at the genome level, and the natural mechanisms of heredity and gene regulation are not bypassed.

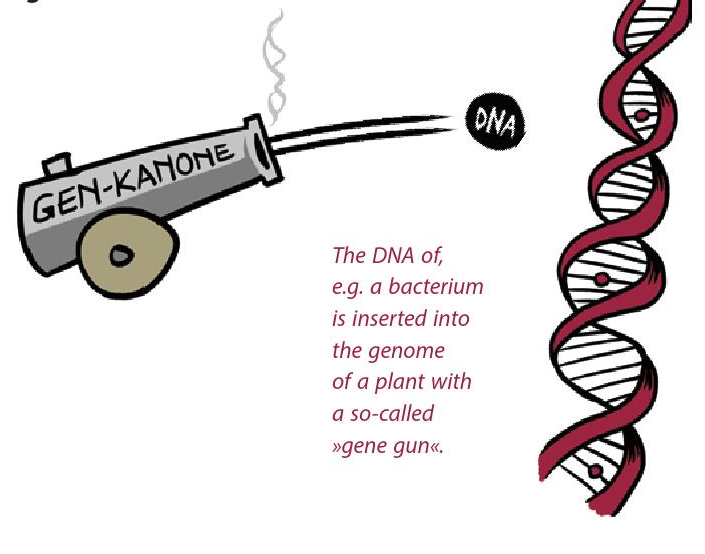

So far, genetic engineering has aimed to introduce specific new traits into plants. This involves introducing “foreign” genes into the plant genome. For example, a “gene gun”4 can be used to introduce a gene from a bacterium into the genome of a plant. The goal is, for example, to introduce a bacterial trait into the specific plant to make it resistant to herbicides. However, other unintended changes and interactions often occur, and the risks associated with these changes must be thoroughly investigated. Genetic engineering creates organisms with biological traits that have not been “validated” by (natural) evolutionary processes. Genetically modified organisms are created using technical processes that directly intervene in the genome; they are not considered as a “whole,” but are limited to the function of individual “genetic building blocks,” and the natural mechanisms of heredity and gene regulation are bypassed.

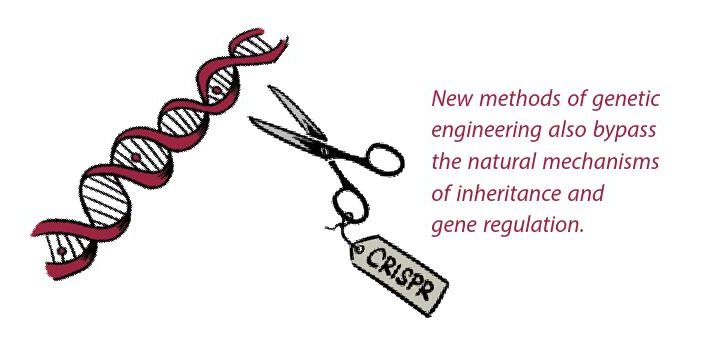

New genetic engineering technologies make it possible to change the genome in an entirely new way, similar to how word processors on our computers allow us to rewrite texts arbitrarily. Thus, these new genome editing techniques are supposed to give us the ability to “rewrite” the code of life arbitrarily.

The most important tools in this process are enzymes that serve as “genetic scissors”5. With the help of so-called “guides”, they target sites in the genome that are to be “reconstructed”. This reconstruction can affect small or large, individual or multiple segments of the genome. The “genetic scissors” can be used to delete genes, change their function, or introduce additional genes.

The application capabilities of CRISPR/Cas are far more extensive than “single point mutations”. For example, there is the possibility of “multiplexing”, meaning the simultaneous mutation of many (identical or different) genes. Such mutations can lead to new combinations of genetic material that would be impossible with conventional breeding. Even if the changes affect only small segments of DNA, they can result in significant alterations and entirely new characteristics in organisms.

“Precision” is a term often referred to in discussions about the safety of these new technologies. In contrast to conventional breeding, where farmers/livestock breeders have no influence over which point in the genome will mutate, geneticists can use genome editing to predetermine both the location and type of mutation. However, this does not mean that this process is safe, since it will always depend on interactions with other genes and with the environment. “Precise editing of individual gene sequences” does not automatically imply safety in any way, since a targeted, precise edit could – depending on the context – lead to serious damage to the organism and its ecosystem.

Moreover, gene editing techniques are prone to errors: it has been observed that the “gene scissors” can cut at the wrong site or that incorrect DNA fragments can be inserted into the organism. Even if everything goes “perfectly,” the use of the “gene scissors” still leads to specific patterns of genetic change that differ from those of conventional breeding. Just like the “old” methods of genetic engineering, genome editing also directly intervenes in the genome, and natural mechanisms of heredity and gene regulation are bypassed. Therefore, the biological characteristics (and risks) of genetically modified organisms differ significantly from organisms that arise during (natural) evolution or from conventional breeding—even if no additional new genes have been introduced.

Even modern life sciences are still far from fully understanding vital biological and evolutionary processes, while often there is greater interest in acquiring profit rather than conducting substantive research on natural interactions. Moreover, genetic engineering applications can create the impression that a living organism is nothing more than the sum of its genes, and the complex evolutionary processes of change and development are reduced to these changes in the genetic code.

Both “old” and “new” methods of genetic engineering essentially bypass the natural rules of gene regulation and inheritance and can lead to changes that are dangerous for the environment. Among other things, there is no process of mutual adaptation of genetically modified organisms to the environment, as would happen during (natural) evolution. The long-term effects of releasing genetically modified organisms and their uncontrolled spread in the environment cannot be predicted, since the properties of GMOs that multiply in the natural environment and interact with natural populations differ significantly from those that can be tested in a laboratory. Thus, these effects may lead to significant disruption of interdependencies in ecosystems, as well as endanger biodiversity and species conservation.

It is clear that in nature the process of inheritance of traits to the next generations follows specific rules. The new methods of genetic engineering are very powerful tools and unlike conventional cultivation methods, they make it possible to change the genetic code by bypassing natural inheritance mechanisms and gene regulation.

Nature has developed many different mechanisms of gene regulation to allow a balance between the emergence of new biological diversity and ensuring species stability. If mutations occur in nature, they are not targeted, but neither are they completely random. The same applies to (natural) genetic exchanges between different species. All of these operate in nature only under specific conditions. Additionally, there are natural selection and adaptation processes that extend over extremely long periods of time. It is not only the (natural) change in genetic material that determines which characteristics will be created in which organisms, but also the interactions between DNA, cells, the organism, and the environment. Nature operates with many small steps that are subject to many controls, and thus changes (mutations) are possible while maintaining species stability.

Conventional cultivation operates through the mechanisms of natural genetic regulation and inheritance. It functions according to the prevailing rules that govern natural biodiversity. If these natural mechanisms are bypassed using technical methods, then ecosystems and humans will (could) suffer serious damage.

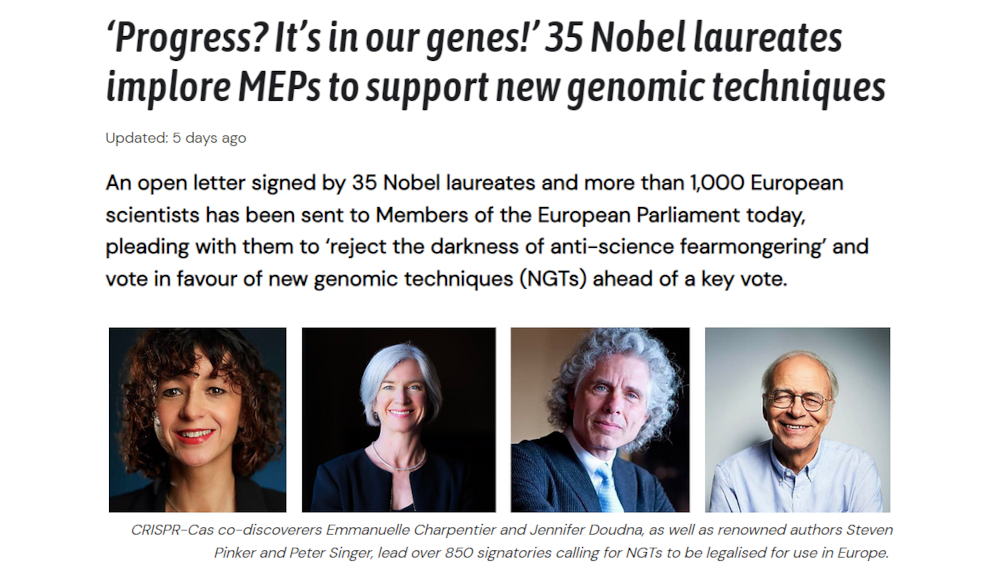

The “letter of the Nobel laureates” that misled signatories regarding the regulation of GMOs in Europe bears the fingerprints of industry everywhere.6

When the news broke that the majority of MEPs on the European Parliament’s environment committee voted in favor of eliminating safety checks, labeling, and liability for new GMOs, the organization WePlanet enthusiastically declared that “it is a tremendous victory, showing that we can defeat the anti-science lobby if we are united and organized.” There is no doubt about the crucial role WePlanet played in this “triumph for GMO deregulation,” through their open letter7, signed by 35 Nobel laureates, “urging Europe not to listen to populist misinformation and ignorance… It is crucial that the voices of these distinguished scientists were heard today”8.

But molecular geneticist Michalis Antoniou has pointed out that the WePlanet open letter – despite the star power of the Nobel laureates and other celebrities who signed it – is completely “empty of scientific substance.” It is also dishonorable. And this comes as no surprise, given the nature of the lobbyists who orchestrated the entire affair.

WePlanet has completed its celebratory statement regarding its successful lobbying, urging its supporters to “donate today to secure more wins like this one!” And it is already offering to cover the transportation costs for its supporters to Strasbourg at the beginning of next month to demonstrate outside the European Parliament, when the MEPs vote on deregulation. And this is not the first protest in favor of GMOs that WePlanet has orchestrated.

Despite its almost constant appeals for donations, WePlanet, formerly known as RePlanet, is in fact generously (and extremely “suspiciously”) funded [9] to promote GMOs, nuclear energy, and synthetic foods. Indeed, it has been accused – and not unjustifiably – of having “all the characteristics of an advanced astroturf organization9, whose real job is to promote industry interests, particularly by undermining EU regulations on agrochemicals and ‘new foods’.” Its co-founder Mark Lynas has also been repeatedly called out for inaccurate, misleading, and even completely fabricated claims.10

Therefore, it is not surprising that WePlanet requested support in its open letter, misleadingly claiming that based on existing regulations for GMOs, “new genomic techniques” (NGTs) are not permitted in the European Union. This is not true, but corresponds to the course that WePlanet has charted with a parallel campaign, Reboot Food11, through which it calls on the EU to “legitimize gene editing, genetic modification and other new reproductive techniques”.

In fact, the use of both new gene editing techniques and older genetic modification techniques is absolutely legal in the EU. Similarly, GMOs, whether created through old-type or new-type gene editing, have long been legal in Europe, both for consumption and cultivation. How else could genetically modified corn have been cultivated here for years, both in Spain and Portugal?

What the GMO industry and its supporters, such as WePlanet, are actually opposing is the fact that GMOs in Europe cannot – at present – be marketed without being assessed for potential side effects, without there being a way to trace their “path,” and without labeling on packaging that would allow consumers and the food industry to know and choose what they want to buy. The deregulation of GMOs (which is now being voted on in the EU) will make it impossible to ensure all these things and thus will create a much more attractive market for GMOs.

However, WePlanet claims in its letter that “a recent report showed that the failure to allow GMOs could cost the European economy 300 billion euros annually in ‘benefit losses’ across many sectors.” However, just like the false claim that GMOs are not allowed, this statement does not clarify that the report promising all these billions to the EU was not written by experts but was the work of Mark Lynas, along with another co-author from the “ecomodernist” Breakthrough Institute12, a US think tank that advocates for “techno-fixes.”

The report was published by Lynas’s employer, the “Alliance for Science,” a pro-GMO propaganda group based in New York and funded by the Gates Foundation13. It was subsequently released in Europe at an event14 funded by WePlanet and the “Alliance for Science,” which are working in parallel to promote the deregulation of GMOs in Europe, as well as to educate young scientists who “will carry the message.”

Despite being deliberately misleading and, as Professor Antoniou says, “lacking scientific substance,” the WePlanet open letter has attracted over 1,000 scientist signatories and has gained significant publicity15, almost certainly due to the support of the 35 Nobel laureates and two celebrities who co-signed it. But these highly publicized celebrity co-signatories are not as brilliant as they appear.

The lead signatories of the letter, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, are superstars in the world of biotechnology thanks to their discovery of the CRISPR/Cas gene-editing tool, which earned them the Nobel Prize. However, as famous as they may be, Doudna and Charpentier are not “neutral” scientists at all. They are biotechnology entrepreneurs who have founded companies16 to manage the licensing of CRISPR technology, among other things, to major GMO and chemical product companies. Prominent among these is DuPont—now Corteva—which allows it to achieve controlled, patent-protected dominance of CRISPR technology in agriculture.

Overall, as revealed by the research of the Italian team Centro Internazionale Crocevia, Doudna and Charpentier are referred to as inventors in 516 patents17 that have been filed globally based on CRISPR technology, 66 of which are European. All of this casts a different light on their support for relaxing the rules regarding the technology in which they have invested so much.

The fourth and fifth signatories of the letter are the other eponymous supporters of it – Steven Pinker and Peter Singer. But once again, there are reasons not to trust the judgment of these “world-famous writers,” as Mark Lynas characterizes them.

The bioethicist Peter Singer is perhaps best known for his long-standing support for animal rights, but far more controversial is his support not only for human genetic engineering but also for infanticide. His writings on the euthanasia of certain newborns with disabilities (Kuhse and Singer, 1985) have provoked outrage and accusations of fascism.18

The renowned psychologist Steven Pinker, like Mark Lynas and his colleagues at WePlanet, is recognized as an “ecomodernist” and is known for his “cheerleading worship” of technological progress. But like Singer, Pinker has also provoked anger, mainly due to his indifference to inequality and his assistance in the legal defense of Jeffrey Epstein. Pinker has also been criticized for his relationship with the Breakthrough Institute and for promoting their texts on climate change.

However, another key signatory of the letter is most likely the key figure, not only for how so many Nobel laureates ended up signing the WePlanet letter, but also for who is actually orchestrating the whole affair. Richard J. Roberts is the chief scientific officer for New England Biolabs, a private biotechnology company whose products reference patents from Dow Agrosciences (now part of Corteva) and Monsanto (which today belongs to Bayer). Roberts is a fanatic advocate of biotechnology, claiming that millions of people will die if genetically modified crops are not adopted, and that opposition to their adoption constitutes a “crime against humanity.”

He also has experience in gathering large numbers of Nobel laureates—often without specific knowledge of the subject matter—in order to create “pressuring” open letters defending the interests of biotechnology.19 In 2020, for example, Roberts gathered 77 Nobel laureates to sign a letter defending Peter Daszak’s EcoHealth Alliance and calling for the reinstatement of its funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which had been suspended due to concerns over its controversial activities involving coronaviruses in Wuhan, activities that some scientists believe may have been responsible for the Covid-19 pandemic.20 It also appears that Roberts “warned” (threateningly) those scientists who were openly discussing such a possibility regarding the origin of the pandemic.

Even more indicative was Roberts’ first attempt to gather Nobel laureates in 2016, when according to an article in the Washington Post, “more than 100 Nobel laureates signed a letter calling on Greenpeace to end its opposition to GMOs.” This letter was based on highly provocative claims that Greenpeace was hindering the development of golden rice – which were subsequently refuted by a leading researcher at the institute that created the rice – even Mark Lynas felt compelled to admit that they were inaccurate and exaggerated.21

Although Roberts was the central figure of this #Nobels4GMOs campaign, it later emerged that another key player was Jay Byrne22, the former director of corporate communications at Monsanto, who also acted as a “gatekeeper” at a venue that hosted a campaign event. Byrne later confirmed to journalist Vincent Harmsen that he had provided public relations guidance to Roberts for a full year before the launch of the #Nobels4GMOs campaign.

After his departure from Monsanto, Byrne started his own public relations firm, v-Fluence, which is located, like Monsanto, in St Louis and has Monsanto among its clients in the chemical and biotechnology sector. Byrne specializes in secret public relations operations and the exercise of covert influence, which, as Vincent Harmsen notes, “includes transferring industry capital to scientists, hiring scientists for public relations purposes and targeting industry critics, while carefully keeping the industry’s participation hidden”.

Byrne was also a public relations advisor to his employer Mark Lynas, the Science Alliance, from its founding in 2014. In fact, Byrne and Lynas are known to have worked together to promote genetically modified crops even before Lynas joined the Alliance in 2014.23

Given that this “born-in-the-industry” renowned doctor was a public relations mentor for over a decade for the co-founder of WePlanet and has also worked closely with Roberts on at least one impressively similar attempt to gather Nobel laureates to influence public discussion on GMOs, it is difficult not to view their latest letter supporting biotechnology as simply a continuation of their industry-friendly path, equally misleading as that golden rice case. Finally, since Byrne is a public relations advisor to Lynas and the Alliance for Science, it also seems likely that he had a role in the report they authored, regarding all these billions in benefits if deregulation occurs.

All of these can explain why people who claim to “defend science” come armed not with science but with a sales bulletin that expresses the interests of industry.

In WePlanet’s letter, there is no explanation as to why French government food safety scientists from ANSES say there is no scientific basis for the deregulation proposals, or why the German Federal Nature Conservation Agency also has concerns about these proposals. Nor is there anything that counters the concerns expressed in numerous statements and letters from other European scientists and academics.24 On the contrary, WePlanet’s letter focuses on the unproven promises made by the GMO industry that new GMOs will finally achieve what previous GMOs have failed so badly at: reducing pesticide use and enabling farmers to address the challenges of climate change—despite data-driven analyses showing that new GMOs can contribute little or nothing to these goals.

The fact that the WePlanet letter is phrased in the language of public relations and marketing, rather than science, is understandable to some extent, because the issue of deregulation does not concern science—it concerns the sales of new patented GMO products. Of course, the WePlanet letter has attracted far more signatures from scientists than any of the documented letters expressing concerns. Perhaps this is understandable in these days of limited budgets and restricted career opportunities, given the enormous funding and the “new jobs and greater economic prosperity” promised by all these billions of euros. Moreover, there is the reassurance of being in the company of 35 Nobel laureates.

But as Philip Stark, associate dean in the department of mathematics and physical sciences and professor of statistics at the University of California, Berkeley, commented regarding the first letter “Nobel laureates in favor of GMOs”: “science has to do with evidence and not with authority… In science we are supposed to support ‘show me,’ not ‘trust me’… Whether you have a Nobel prize or not.”

Ultimately, even the most reputable scientific institutions can make major mistakes, as noted recently by Le Monde’s scientific correspondent, Stephane Foucart, in an article in which he referred to the abuse of scientific authority as a “scourge.” Foucart gives many examples of national scientific academies acting as transmission belts for industry. At one time, for example, the French Academy of Sciences was still another bastion of climate skepticism. It also spoke out against the precautionary principle in shale gas research. Similarly, the statement from the Georgian Academy supporting the full privatization of agricultural advisors turned out to have been written by former executives and consultants from the pesticide industry. And as late as 1996, the National Academy of Medicine was calling for asbestos use to continue.

But the current letter of the Nobel laureates is not based merely on invoking authority and unsubstantiated promises. As Professor Antoniou also noted, they also resort to insults. Thus, according to the letter, those who disagree with deregulation are “lost in ideology and dogmatism” and simply “deny scientific progress.” They are also called “anti-science reactionaries in the bubble of Brussels” who are lost in the “darkness of anti-scientific terrorism.”

This type of aggressive language is used by Jay Byrne—and by Lynas and the Alliance for Science, whom he has guided—who refers to the term “anti-science” to a nauseatingly high degree. But is this really the way that the views of ANSES experts and the German Federal Nature Conservation Service or all other scientists who have serious concerns regarding deregulation can be addressed?

Responding to the letter of the Nobel laureates, Professor Jack Stilgoe, who teaches courses on science and technology policy, responsible science and innovation, and governance of emerging technologies at University College London, pointed to an article he had written in the past25 in which he argued that the term “anti-science” is a weapon used against those who ask uncomfortable questions. He says that “it reflects a privatization of the idea of progress that is dangerous for science and society. Once science is considered inextricably linked to a particular path – especially when that path is GMOs – discussion becomes impossible. I know dozens of scientists who are against GMOs or against a particular type of GMO. Are they anti-scientists?”

Professor Antoniou makes a similar observation: “I am not the only scientist in the mainstream academic community and specialist in molecular genetics and genetic engineering technologies who has serious concerns about the European Commission’s proposal to deregulate GMOs. We are not “anti-science reactionaries in the Brussels bubble,” which in any case is a false and defamatory description of NGOs in Brussels and elsewhere in Europe who challenge the deregulation of GMOs. My experience from collaborating with these organizations is that they are guided by scientific evidence and a responsible determination to put people and the environment above profits.”

The letter from the Nobel laureates raises real doubts about whether those behind it share this determination.

Translation: Wintermute

- Source: www.testbiotech.org ↩︎

- There is one exception: genetically modified corn (MON810), which is occasionally cultivated on a small scale (https://kurzelinks.de/pits) ↩︎

- Stm: The term in English is “conventional breeding” and means crops in which mutations also occur naturally, e.g. crossing two different varieties of the same species. ↩︎

- Stm: It is not a simulation, but a tool with which “foreign” genes are introduced into organisms and it has the shape of a gun. You can see it by searching the internet for “gene gun”. ↩︎

- Stm: Here is a comparison… ↩︎

- https://www.gmwatch.org/en/106-news/latest-news/20368-laureates-letter-misled-signatories-about-gmo-regulation-in-europe-has-industry-s-fingerprints-all-over-it ↩︎

- https://www.weplanet.org/ngtopenletter ↩︎

- https://www.weplanet.org/post/envi-committee-back-ngts-in-historic-vote ↩︎

- Note: The term astroturf is the name of the largest company that produces artificial grass for stadiums, etc. It is also used as a term (astroturf movement) to describe manufactured movements/actions which appear to “sprout” spontaneously and “from below”. Something like the opposite of “grassroots movements”. ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/myth-makers-l#Lynas ↩︎

- www.rebootfood.org ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/myth-makers-b#Breakthrough_institute ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/myth-makers-c#CAS ↩︎

- https://events.euractiv.com/event/info/new-genomic-techniques-what-lies-ahead ↩︎

- E.g. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/jan/19/nobel-laureates-call-on-eu-to-relax-rules-on-genetic-modification ↩︎

- More: https://www.greens-efa.eu/files/assets/docs/chapter_6_gene-editing_technology_is_owned_and_controlled_by_big_corporations.pdf ↩︎

- https://link.lens.org/XShwHKpwL3b ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/main-menu/news-menu-title/archive/85-2014/15318 ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/106-news/latest-news/17077 ↩︎

- More: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/health/wuhan-coronavirus-laboratory.html ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/106-news/latest-news/17316 ↩︎

- More: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/myth-makers-b#Jay_Byrne ↩︎

- More: https://spinwatch.org/index.php/issues/science/item/5522-biotech-ambassadors-in-africa ↩︎

- As here: https://newgmo.org/2023/11/19/open-letter-serious-concerns-about-the-eu-commission-proposal-on-new-genomic-techniques

here: https://ensser.org/publications/2023/statement-eu-commissions-proposal-on-new-gm-plants-no-science-no-safety

and here: https://www.testbiotech.org/sites/default/files/Expert_statement_risks_of_NGT_plants.pdf ↩︎ - https://jackstilgoe.wordpress.com/2012/02/21/anti-anti-science/ ↩︎