The phrase of Mark Twain (which he himself attributed to British Prime Minister Disraeli) is now widely known: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Despite its exaggeration, this phrase captures a truth. Statistics can easily be used as a powerful ideological weapon. A basic source of its power naturally lies in the systematic use of numbers and equations on its part. Since numbers have reached the point of functioning almost as metonyms of truth in modern Western societies, whatever is expressed as a number automatically acquires validity, even if it is merely a veneer of truthfulness. However, the deployment of numbers alone is not sufficient. The insidious aspect of statistical “lies” lies in the fact that they are neither “simple lies” nor even “blatant lies,” in the sense of the incorrect application of a certain equation or the “cooking” of data to fit predetermined conclusions and preconceived decisions. Sometimes such abuses do indeed occur. However, statistics possess the magical property of producing flimsy conclusions by following a correct (from a mathematical perspective) procedure.

A tangible example here would perhaps be useful; naturally, only the therapeutically “sprayed” are entitled to make syllogisms that lead to recent states of completion with a scientific-statistical twist. Suppose a pharmaceutical company wants to test a new preparation of theirs, for example, a “miracle vaccine” against the frog virus. To calculate the effectiveness of the new vaccine, it uses 2,000 volunteers as experimental subjects. It administers the vaccine to half of them and gives nothing (or a placebo) to the rest. The first group constitutes the so-called experimental group, and the second the control group. The purpose, of course, is to calculate the vaccine’s effectiveness by comparing the results of the two groups. If fewer cases of the frog virus appear in the experimental group, then the vaccine can be considered effective. The crucial question, however, concerns exactly how this effectiveness is quantified. Suppose, then, that in the experimental group only one person caught the virus, while ten cases were found in the control group. Delighted, the company can announce in triumphant tones that its vaccine has 90% effectiveness, since it reduced the cases by that percentage ((10 – 1) / 10 = 9 / 10 = 90%). Let your children go frog hunting again!

So far, there is no “cooking” of the data, no incorrect calculation. The “falsification” lies elsewhere. The number announced by the company is the so-called relative risk reduction index. This is calculated by looking only at the cases (1 from one group plus 10 from the other group) and ignoring all the remaining experimental subjects who did not catch the virus. It completely ignores, that is, the transmissibility of the virus, previous possible immunity against it, and a host of other factors that may reduce the likelihood of catching it without the help of any vaccine. It ignores how many did NOT catch it in either group (placebo, 990) or the other (999).

There is therefore another number that makes this exact calculation and is called the absolute risk reduction index. Based on the numbers we have given above, this index comes out to be… 0.9% (10/1000 – 1/1000). In practice, therefore, the actual probability of getting infected in the general population by taking this specific vaccine is reduced by something less than 1% and not by 90%. And this number concerns only the probability of getting infected and not of getting seriously ill or dying. Moreover, it is compared against a control group that receives no alternative treatment. What would this number be if the comparison concerned cases of severe illness and in comparison with other treatments? Certainly something even smaller than this modest 1%. If in addition we had to include possible side effects…; Perhaps then there would even be a chance for this number to turn negative, which would mean that the harms outweigh the benefits;

The differences between these two indicators are not at all unknown among specialists; moreover, the guidelines one can read regarding the correct presentation of such experimental results are clear: both the relative and absolute risk reduction indicators must always be reported. Is this practice always followed? Of course not – or perhaps the data is hidden somewhere in a small table towards the end of the article and you have to calculate the indicators you want on your own. Does this matter for creating impressions and front pages? Not at all. In the air remains to circulate some number close to 90% and the company remains covered since it cannot be accused of any distortion.

The use of statistics is not, of course, limited only to medical circles. It has become almost a lingua franca for specialists and not only. What is your favorite player’s three-point shooting percentage? What is your IQ (IQ is measured based on a statistical distribution with 100 as the average)? Why do you pay higher insurance premiums as a new driver (statistically speaking, new drivers have a higher probability of being involved in an accident)? Is your blood triglyceride level dangerous (the “risk thresholds” of medical indicators are often calculated using statistical tests)? What exactly is the trajectory of particles in CERN’s accelerators (yet, particle trajectories cannot be seen “with the naked eye”; they are reconstructed from signals produced by the accelerator, using statistical algorithms as well)? The fact that statistics has managed to acquire such a strong epistemological status that we now even speak of “statistical laws” is certainly not a historical accident. The question about this rise of statistics becomes even greater if one considers that the traditional form of scientific knowledge (from the 17th century onward) was that expressed in the form of absolute and immutable laws1. In Newtonian mechanics, there is no room for planetary orbits that are “approximately” determined. The orbits of celestial bodies are precisely determined by the equations of gravitational forces; any deviations are due only to imperfections in observational instruments and not to any inherent uncertainty in the observed objects.

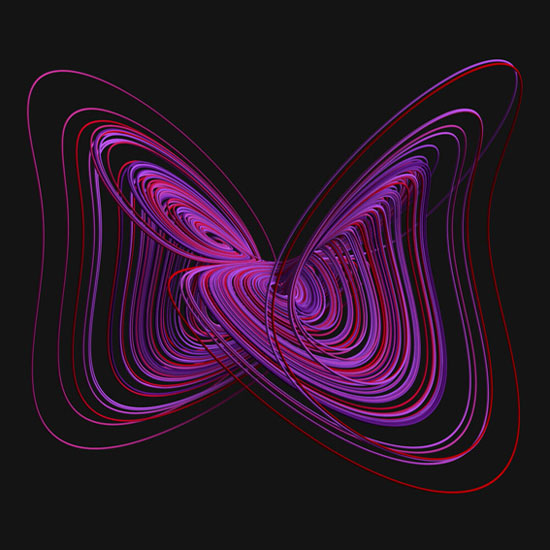

As is known, this very reversal was achieved by quantum mechanics, the statistical interpretation of which eventually dominated among German physicists of the Weimar Republic. For quantum mechanics, the uncertainty of the physicist as he tries to measure the properties of a particle is not the result of any (potentially eliminable) limitations of his instruments. No matter how much he improves their resolution, he will never manage to measure the position and velocity of a particle with absolute accuracy. The particle itself now resists the observer’s gaze, manifesting an endless uncertainty. Even the word “particle” itself can only be used abusively, to the extent that it evokes images of microscopic spheres moving with a definite velocity vector and colliding much like billiard balls. With the eyes of quantum mechanics, this is an outdated image, deriving from the old, classical, mechanistic conception of nature, as introduced by Newton and Galileo. The new physics transcends the limitations of the old by treating the “particle” as a probabilistic wave function, as a statistical cloud which condenses to a point only at the moment of observation.

Was the statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics a one-way street? In other words, was it necessary to interpret the new functions that more successfully described the behavior of particles as “statistical clouds”? Was it absolutely necessary to abandon the robust determinism of classical physics at all costs? For many physicists of the time (including Planck and Einstein), rejecting determinism, which had yielded so much fruit in physics over the previous centuries, constituted something akin to sacrilege. Einstein’s famous phrase, “God does not play dice,” is well known. These dissenting physicists were not simply fossils destined by fate to fade into the margins, as the victorious perspective might wish to see them today, reading the developments of that time through the lens of the present. Less known than Einstein’s objections is the fact that even after the dominance of the statistical interpretation, systematic attempts were made to provide a deterministic interpretation of quantum mechanics. A fundamental approach was the hypothesis of so-called “hidden variables,” which reduced an apparently statistical system to a deterministic one2. David Bohm’s theory (from 1952) is perhaps the most well-known such case3. The interest in Bohm’s theory lies in the fact that the equations it leads to are exactly the same as those of the statistical interpretation, which in turn means that there is no way to distinguish one from the other based on their experimental predictions. They are exactly the same in both cases. No experiment can confirm one while rejecting the other. Whether Bohm’s deterministic interpretation is equivalent to the well-known statistical interpretation remains an open question and holds a rather marginal position in the interests of most physicists. Even if it is proven, however, that Bohm’s theory is not viable, the mere fact that this issue, from a purely mathematical and technical standpoint, is still considered unresolved (even though more than half a century has passed since then…) indicates something else of critical importance: that the acceptance of the statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics during the interwar period was not made solely for reasons of technical superiority.

The other reasons that could be put forward as part of the explanation for the emergence of statistics (interpretation of nature) have to do with the broader social and intellectual climate of interwar Europe and Germany in particular4. Partly as a result of Germany’s defeat in the First World War and the broader realization of the destructive consequences of technical progress – perhaps for the first time since the Enlightenment, techno-scientific progress was disconnected from morality – scientists found themselves in an extremely difficult position. It was now almost impossible for them to legitimize their position by appealing to a supposed inherent progressive tendency of science. The climate had now reversed, and declarations against dry rationalism – materialism, analytical philosophy and consequently also against determinism – which had been inextricably linked with the previous expansive phase of science – became commonplace. Even in philosophy, Bergson’s vitalism and Heidegger’s existentialism (with their constant references to anonymous masses moving without trace of reflection, that is, “mechanically”) can be read as symptoms of the crisis of traditional determinism5. The totality (and the search for it) acquired new meaning and clear priority over parts that move according to blind forces. The crisis in physics (but also in mathematics, as evidenced by Hilbert’s program for their foundation) seemed almost inevitable. The statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics emerged at the right moment to save scientists from their apparent slide into arbitrariness. The resistance of particles against their suffocating embrace by the deterministic equations of classical mechanics was understood (also) as an escape to a field of greater freedom.

If statistics managed to conquer physics at its core, then it was perhaps expected that it would eventually expand into much less “hard” fields. It was not only adopted by biology, but came to be regarded as the universal paradigm for validating knowledge. Its dominance has been confirmed in recent years by the emergence of so-called Big Data and artificial intelligence algorithms – which are themselves statistical in nature. We next present an excerpt from a 2008 article that created quite a stir when it first appeared6:

“At the petabyte scale, information is no longer a matter of classification and arrangement in three or four dimensions, but a matter of statistics, for which the number of dimensions will be indifferent. It requires a completely different approach that will be free from the requirement of visualizing data in its entirety. It forces us to see data primarily through a mathematical lens and only secondarily to find its context. For example, Google needed nothing more than applied mathematics to conquer the world of advertising. It never pretended to know the slightest thing about the culture and conventions of advertising – its only assumption was that it would manage to come out ahead simply by having better data and better analysis tools. And it was right.

Google’s basic philosophy is that “we don’t know why a particular page is better than another.” If the statistics regarding incoming links tell us that it indeed is better, then that’s all we need. No semantic or causal analysis is necessary. This is why Google can translate from languages it doesn’t actually “know” (given the same amount of data, Google can just as easily translate Klingon to Farsi as it can French to German). And it’s also why it can find which ads match specific content without knowing or assuming anything about either the ads or the content.

…

Here we are, standing in front of a world where massive volumes of data and applied mathematics will replace all other tools. Forget all theories about human behavior, from linguistics to sociology. Forget taxonomies, ontologies and psychologies. Who knows why people behave the way they do? The point is that they do behave, and we can record and measure this behavior with a fidelity that was unimaginable until recently. If we have enough data, then the numbers speak for themselves.

However, the target here is not so much advertising, but science. The scientific method is based on testable hypotheses. These models are largely systems, visualized within the minds of scientists. Then the models are tested and experiments are what ultimately confirm or refute the theoretical models of how the world works. This is the way of science for centuries.

Part of scientists’ education is to learn that correlation does not equate to causation and that you cannot draw conclusions simply based on the fact that X correlates with Y (which could be mere coincidence). You must, on the contrary, be able to understand the hidden mechanisms that connect these two. Once you have a model, then you can reliably make the connection between them. Having data without a model is like having noise alone.

Με την εμφάνιση των δεδομένων μαζικής κλίμακας όμως, αυτή η προσέγγιση της επιστήμης – υπόθεση, μοντέλο, έλεγχος – καθίσταται απαρχαιωμένη. Ας πάρουμε το παράδειγμα της φυσικής: τα νευτώνεια μοντέλα δεν ήταν τίποτα άλλο παρά χοντροκομμένες προσεγγίσεις της αλήθειας (λανθασμένα όταν εφαρμόζονται στο ατομικό επίπεδο, αλλά κατά τ’ άλλα χρήσιμα). Πριν εκατό χρόνια, η κβαντομηχανική, βασισμένη στη στατιστική, μάς έδωσε μια καλύτερη εικόνα – όμως κι η κβαντομηχανική είναι απλώς ένα ακόμα μοντέλο, που ως τέτοιο, είναι κι αυτό ελαττωματικό· καρικατούρα μιας πραγματικότητας που είναι πολύ πιο σύνθετη. Ο λόγος που τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες η φυσική έχει διολισθήσει προς μια θεωρητική εικοτολογία περί εντυπωσιακών ν-διάστατων ενοποιημένων μοντέλων είναι το γεγονός ότι δεν γνωρίζουμε τον τρόπο για να τρέξουμε τα πειράματα εκείνα που θα διέψευδαν όλες αυτές τις υποθέσεις – απαιτούνται πολύ υψηλές ενέργειες, πολύ ακριβοί επιταχυντές, κ.τ.λ.

Biology is heading in the same direction. The models we learned in school about “dominant” and “recessive” genes that guide a strictly Mendelian process have proven to be ultimately a simplification of reality even more coarse than that of Newton’s laws. The discovery of interactions between genes and proteins, as well as other epigenetic factors, has shaken the view that DNA constitutes something like fate, and moreover, we now have indications that the environment can influence traits that are heritable, something that was once considered genetically impossible.

…

Now there is a better way. With petabytes we can say: “correlation is enough for us.” We can stop looking for models. We can analyze the data without assumptions about what we are likely to find. We can feed computational clusters (the largest that have ever existed) with numbers and let statistical algorithms find the patterns that science itself cannot find.

Within its (philosophical) naivety7, the specific article proved to be in a sense prophetic, expressing with impunity already existing tendencies within science. In 2008, artificial intelligence had not yet experienced its current glories. Now it is considered almost mandatory for every simulation of a natural or biological system to be accompanied by an analysis of the results based on machine learning algorithms. The search for some statistical correlation seems to have replaced the search for a Law that explains phenomena through strict causal chains8.

From quantum mechanics to modern artificial intelligence (with chaotic systems as an intermediate stop), determinism appears to have gradually lost its strong primacy within scientific thought. On the other hand, the concept of probability in its modern form did not suddenly emerge in the early 20th century. It has a longer history, yet remains a distinctly modern concept. The date of its birth, if such a date must be pinpointed, is already found in the 17th century (the century in which mechanism triumphed in physics)9. In 1662, the famous book La Logique ou l’art de penser (Logic or the Art of Thinking) was published in France, a logic manual that remained in wide circulation until the 19th century. Toward the end of the book, for the first time, reference is made to a concept of probability that lends itself to mathematical treatment. Until then, the term “probable” was used within the framework of scholastic philosophy, but it was not yet connected in any way with (Aristotelian) logic or mathematics. Something was characterized as “probable” not because there were tangible elements supporting it, but because it was widely accepted by the “reasonable and intelligent” members of society. It therefore carried strong elements of moralizing. For scholastic philosophy, only those judgments and conclusions that could be demonstrated through strict proof were allowed to be characterized as “knowledge.” Everything else fell into the category of opinion (opinio). A greater degree of truthfulness (probabilitas) was attributed to an opinion if it was widely accepted by the more educated and pious social strata.

The concept of probability in its newer sense found room to develop precisely in the gap between knowledge and belief, especially through the work of Renaissance physicians. To the extent that they did not have access to the internal functioning of the body—and thus to the strictly causal mechanisms leading to a disease—they had to rely on symptoms, that is, external signs provided by the body. In this way, of course, it was not possible to attain certainties of strict accuracy. However, they could make use of bodily symptoms, interpreting them as signs offered by the suffering body. And in a subsequent step, all of nature could be seen as one great book (with God as its author, naturally), whose signs could be deciphered by the trained scientific eye. The next issue to be resolved concerned the reliability of these signs. Could one trust them? Was it possible to quantify this reliability? The concept of frequency (and percentages) came here to provide the solution. Even if the certainty of traditional knowledge was not feasible, a high frequency of occurrence of a phenomenon was sufficient to provide practically useful guidance. In this way, knowledge was able to acquire degrees of truthfulness. Leibniz was among the first to systematically employ this idea. Starting from the notion that all thought can be analyzed into atomic units, he advanced a bold proposal—hypothesis: the possibility of constructing a machine capable of producing all possible combinations of these units of thought and subsequently analyzing them, while simultaneously calculating their probability. For Leibniz, therefore, probabilities were not merely a matter of frequencies; they constituted a fundamental component of thought (they numerically expressed the certainty of reasoning), thus acquiring a special epistemological status.

The fact that probability theory began to develop almost in parallel with classical, deterministic mechanics does not constitute a paradox, no matter how much it might appear so at first glance. In reality, the opposite is true! Probabilism presupposes, as its negative complement, mechanism. Only after nature, through mechanism, was relieved of the burden of teleology could it be conceived as the sum of individual bodies, each moved by forces entirely external to it, like a machine that itself can never offer any resistance. The reaction against such conceptions, if one is not willing (for better or worse) to resurrect vitalistic or teleological ideas, can easily take the form of “randomness.” Not just any randomness (Chance—Fortuna—was, after all, not unknown in ancient times, even being represented in the form of a deity), but specifically a randomness that can be measured, and thus controlled to a greater or lesser extent.

For the history of probability and statistics, the element of measurability is crucial not only for strictly philosophical reasons, but also for political ones. Although at the beginning of the 20th century physicists saw in statistics a way out of determinism, this extreme contrast was by no means self-evident in the 18th and 19th centuries. On the contrary, to the well-known laws of nature there gradually came to be added also “statistical laws,” without this term being considered inherently contradictory10. The rhetoric about statistical laws became so inflationary and came to be applied to such diverse fields (from games of chance to the analysis of suicide and crime rates) that eventually in certain circles there even began to be talk of so-called “statistical fatalism,” namely the idea that if a curve gives us specific percentages for human behavior, then this implies that human subjects are not free to avoid it. When, of course, we are talking about human behaviors (and their control), the issue cannot be philosophical.

The (easy, but rather unknown) etymology of the word “statistics” already provides some indications of its strong political dimension. In English, the word for “state” is “state” while in German it is “Staat”. It was the Prussian intellectual of the 18th century, Gottfried Achenwall, who first proposed the use of the word “Statistik”, defining it as the “collection of notable facts about the state”. As a concept, therefore, statistics began its journey as discourse about the state; but also from the state. Just as physics was the science of nature, statistics (in Greek, the “state science”) would become the science of the state. But what exactly could the state be interested in? Almost everything. About when and where one was born, about where one went to school, how many grades one completed, whether one was vaccinated, whether one got married, whether one had children, about the profession one practices, about one’s physical condition and whether one is able to bear arms, about when and how one died, etc. All this torrent of numbers and statistical data would ultimately allow the authorities to make an assessment of the state’s robustness. But at the same time, it would also function as an “objective” judge, as an “impartial” mediator between conflicting social strata.

The interest in numbers, averages, and deviations was not limited only to human subjects. Anything that needed to be measured, if possible, especially if it involved large scales. The (first) industrial revolution (and industrial warfare) would give an additional boost to statistics, since mass production using machines required the strictest standardization of components, raw materials, and final products. For a machine to function, it needs pure materials and precision parts, without significant deviations in size, strength, and other properties11. And it needs them in large quantities. The industrial revolution did not require only steam engines and coal, but also numbers, many numbers, which would take care to define what is “normal” and what is “deviant.”

For 19th-century statisticians, identifying patterns had become a major concern. Only now, it had to involve people in a more specific biological way. Since everything was becoming an object of measurement, the same could be done with human biological characteristics. The goal was, first of all (as the Belgian Quetelet would express in the 1830s), to discover the “average man.” But what was the value of this “average man,” who, as such, might not even exist as a real subject in the actual world? It was not about finding some average values for humanity as a whole, but about constructing certain “objective” profiles for specific population groups, for characterizing entire “races.” It was no longer cultural or linguistic traits that defined a “race,” but its biological characteristics, which could be measured accurately to derive average values for its “normal” subjects. This was, of course, one of the starting points of eugenics. The same distributions would later be used by the famous Galton, this time focusing on deviations rather than averages (following the logic of enhancing the extreme, positive traits of a group). In any case, if it was now possible to map out the curves of various groups, this opened the way for large-scale interventions aimed at strengthening some characteristics or suppressing others. In 1860, the English bureaucrat William Farr could proclaim loudly:

“The statistical discoveries of a nation are a beacon for all nations. Despite fires, instability of winds, uncertainties of life, and changes in people’s minds and living conditions, upon which depend fires, shipwrecks, and deaths, they are nevertheless subject to laws as immutable as gravity and fluctuate within certain limits, which the calculus of probabilities can determine in advance. The same applies to crimes and other voluntary acts, so that even offenses are subject to the same law. Should we build a fatalistic system on such a basis? No, because statistics has revealed to us a law of variations. If you introduce a ventilation system in unventilated mines, then you replace one law with another. These events are under control. Some tribes, however, commit violent crimes in greater proportion than others. Certain classes are more dangerous. However, since people have the power to change their tribe, they therefore also have the power to change human behaviors within certain limits, which statistics can indicate to us.”

If one examines macroscopically the evolution of scientific thinking through the centuries of modernity (from the 17th century onward), then one can observe the following pattern. During the 17th and 18th centuries, mechanism and determinism clearly held the reins. Nature was understood primarily as a great machine. Just as humanity was conceived as homo faber, so too was nature’s “author” (God) to be conceived as a great craftsman, a deus faber. The statistical method’s vigorous entrance onto the scene in the 19th century (although preliminary processes had started earlier) did not immediately bring about a complete reversal of the previous paradigm. On the contrary, the aim was to employ statistics in describing large-scale phenomena in a way that would resemble that of traditional physics: through the discovery of (statistical) laws possessing the force of universal powers. It was only in the early 20th century that statistics (appeared to) turn directly against determinism, when it came to be interpreted in more “liberal” terms.

The remarkable aspect of this entire trajectory is the (at least in broad terms) convergence between the shifts in the conceptualization of natural law and the transformations in the form of the modern state. Just as the state, at its inception, required a sovereign whose power was to be regarded as unified and continuous throughout his domain, so too was nature expected to submit to the deterministic and inviolable laws of classical mechanics, which applied without exception or deviation. Once this initial form of the state had gained solid footing, the next step in the 19th century was its bureaucratic organization into a more paternalistic form; in other words, the impersonal and “objective” recording, categorization, and “care” of its citizens. Alongside the deterministic laws of mechanics came the laws of statistics, with their measurements, averages, and deviations. Upon entering the 20th century, the state did not entirely shed its paternalistic character (yet). However, it added to its arsenal a veneer of mass “democracy,” in order to align with the reorganization of production and consumption according to an equally mass-based model. Customs, both social and scientific, also had to follow this more “liberal” direction. Statistics thus managed to raise the banner of liberation from the shackles of determinism.

It is important to understand here that statistics, as applied to quantum mechanics, has not been completely detached from the demand for some sophisticated theory to serve as a foundation. Quantum mechanics is far from throwing theory into the trash. It does not simply require theory. It requires much more and far more sophisticated theory in order to eventually produce its equations. The complete disconnection of statistics from any theoretical requirement, as demanded by various enthusiasts of modern machine learning, constitutes a truly postmodern phenomenon. From this perspective, statistics thus appears to conform to the logic and ideology of the neo-liberal state, which has nothing to offer and needs no “grand narrative” and no protection for its “independent” and “free” subjects.

It is questionable how statistics, at some point a century ago, came to be seen as a path to freedom. Insofar as it was a response to mechanism, the best it can offer, as its negative complement, is the “freedom” of randomness without purpose or direction, the “freedom” of the dice roll; that is, ultimately, the “freedom” of the inorganic and the dead. Even if used for more mundane and practical purposes, as an aid to decision-making, its utility at the individual level remains extremely dubious, especially when probabilities are distributed with a balance. If I know that a given action of mine has a 45% chance of leading to outcome A and 55% to outcome B, what is the real value of such “knowledge” to me as an individual? Practically indifferent, someone might say. For a company, however, or for a state, or for anyone managing populations on a large scale, this small difference can translate into millions of profits or millions of dead on the battlefields. Indeed, then, statistics opened corridors of freedom: for the state itself, to and from its subjects, for the profitable biopolitical management of them.

Separatrix

- See At the Door of (Natural) Law, Cyborg, vol. 29. ↩︎

- It is claimed that the famous von Neumann proved in 1932 that hidden variables cannot exist, something that was later disputed. ↩︎

- See Philosophical Concepts in Physics, J. Cushing, ed. Leader Books, trans. M. Orfanou, S. Giannellis. ↩︎

- See The crisis in Physics and the Weimar Republic, PEC, ed. Th. Arampatzis – K. Gavroglou. ↩︎

- Surrealism in art, which flourished at the same time, can also be read as such a symptom. ↩︎

- At the well-known Wired, with the title “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete”. ↩︎

- As a critique, see, for example, The end of theory in science?, Massimo Pigliucci, EMBO reports, 2009. ↩︎

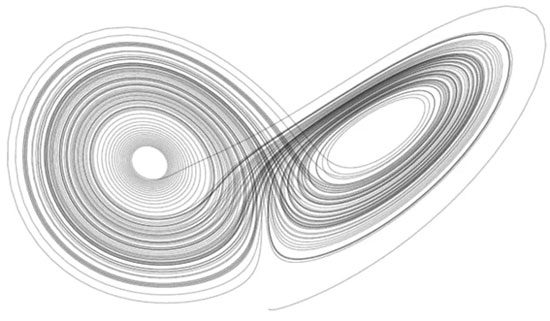

- After quantum mechanics, strict determinism had suffered yet another blow with the emergence of the theory of chaotic and dynamic systems from the 1970s. Strictly speaking, chaotic systems continue to be deterministic. The inability to predict their behavior is due to their sensitivity to the initial conditions from which they start. However, if this sensitivity is so great that no instrument can discern the necessary differences in these conditions, then practically the system becomes non-deterministic. ↩︎

- See Ian Hacking’s “The Emergence of Probability: A Philosophical Study of Early Ideas about Probability, Induction and Statistical Inference”, published by Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- See The Taming of Chance, by Ian Hacking, Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- A fact that played a role even in the rise of genetics. See For an anti-history of genetics, Cyborg, vol. 24. ↩︎