The (flying) drones, or otherwise UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicle), became internationally known as an American invention, at the beginning of the NATO invasion of Afghanistan. Against lightly armed insurgents: a remote-controlled airplane, with its operator safe in some base in Europe or even on American soil, equipped with Hellfire missiles and a camera, could fly for hours over the mountains and valleys of Afghanistan, “searching” for targets. What “searching and finding targets” via a flying camera and from thousands of kilometers away could mean became clear quickly: anything that “looked (to the operators) suspicious” was bombed. Weddings, baptisms, gatherings of people in open spaces, became part of the Western “war on terror” repertoire, primarily driven by the American military. And the term “collateral damage” was born precisely thanks to this new weapon; the beastly distance and the even more beastly “difference in situation” between the shooter and the targets (the shooter in some office in front of screens, the victims in the highlands of the Hindu Kush…); and of course the ease of killing whatever you “think is…”. The Taliban repeatedly accused the high-tech NATO army of cowardice, defending a kind of warfare (“close combat”) that has long been obsolete… But what else would one expect from “primitives”? (They simply drove out the high-tech occupiers after 20 years of occupation…)

With UAVs making their first appearance in February 2001, drones seemed like something akin to small-scale remote-controlled helicopters: a significantly cheaper and safer killing machine, albeit not a technological leap in warfare. Essentially, remotely piloted aircraft were a German invention during World War II, quickly copied by the British and American armies: smaller-sized replicas of airplane types already in use, radio-controlled, as “flying bombs” against visible targets (primarily ships). They did not achieve great success, mainly due to limitations in radio-control technology. From this historical perspective, Predators and MQ-9 Reapers (the two most well-known types of American UAVs), whether as “reconnaissance” or “reconnaissance/strike” vehicles, could be considered improved descendants of those early World War II attempts, especially against opponents who had no means to counter them, neither radar nor anti-aircraft weapons. Ultimately, when the Taliban learned how to hide, UAVs were deemed weapons of limited effectiveness and value (by NATO headquarters), given that they could never have imagined facing mass organized armies: according to Western military headquarters, the use of such weapons would dramatically shorten a war – a war as they envisioned it: against weak opponents. That, and no further.

The war in the Ukrainian battlefield changed these dynamics. Neither Moscow nor Kyiv had initially focused much on this type of weaponry. However, Tehran (which for decades lacked high-tech military aircraft) and Ankara (which, largely equipped with American aviation assets, was dependent on its ambiguous relations with Washington) saw in drones a promising and versatile substitute for traditional air forces. Each of these states invested heavily in the technology and its “alternative” capabilities, taking into account the significantly lower cost of developing drone fleets and the ease of their deployment. Ankara, in particular, had the opportunity to test its creations live—first in Libya (supporting General Haftar) with limited success, and later in the recent brief war between Armenia and Azerbaijan (over Nagorno-Karabakh), siding with the latter and delivering devastating blows against the Armenian army, which had neither the awareness nor the methods to counter this aerial weapon.

In the Ukrainian battlefield, the use of drones must initially be attributed to the advice and guidance provided by Tehran to the rather hesitant Moscow, and subsequently to the assessment of the matter by Kyiv’s Western allies, primarily London and Washington. Before the first year of the war there was completed, in early 2023, a good dose of the 4th industrial revolution was added to a confrontation that was simultaneously a la 1st World War (trenches, barbed wire…), a la 2nd (tanks, bombers…) and a la 3rd (helicopters…). Where the use of drones by NATO and especially the American military in Afghanistan and Iraq was “selective,” with individual relatively expensive “pieces” being used without risk, in the Ukrainian battlefield drones are used by the hundreds and thousands, while continuous efforts are simultaneously made to develop countermeasures.

Machines against machines

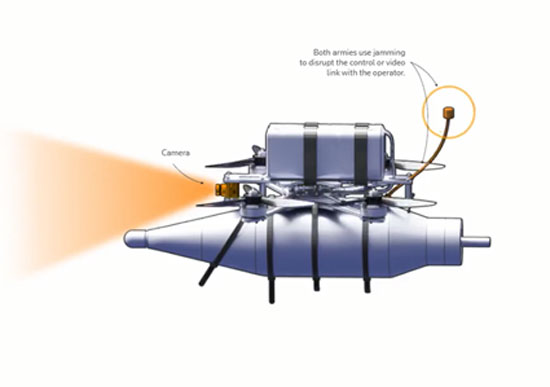

The most substantial (and lethal) “change” in the construction and use of drones (compared to the “heavy” American Reapers) on the Ukrainian battlefield is the so-called FPV (first personal view). They come in various forms but are generally quite cheap quadcopters equipped with a camera and a (relatively small) bomb. While flying without a predetermined target in an area where such targets need to be located, the operator identifies what is worth striking and directs the drone there. If it is a vehicle (tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery), the drone becomes “suicidal”: it crashes at the point the operator considers most vulnerable—destroying and being destroyed. If, on the other hand, it is trench warfare, the FPV will function as a “bomber,” it will “release” its small bomb (usually with fragmentation explosives…), and then return to its base. Whether through one method or the other, FPVs are systematically used, and against personnel—against exposed soldiers1.

Similar in terms of the “spirit” is the construction/use of floating drones, mainly from Kyiv, with English technical assistance. Some versions of land-based drones (like small crawlers) have also appeared from the Russian side, but they don’t seem to have been used beyond trials.

The weak point of these weapons is their radio contact with their operator/base. The radio frequencies of this communication. And exactly there, in parallel with the generalization of their use on the Ukrainian battlefield, the jamming technology began to develop; efforts to cancel their remote guidance. As (relatively) cheap is the mass production of these offensive drones, so (relatively) cheap is the construction of defensive jammers… but at what frequency? This “dialectic” of signals began to evolve just as fast (if not faster) as the use of drones, since each new “batch” communicated with its operators at a different frequency, in order to avoid (previous) jamming; “multijammers” began to appear and be tested, across frequency spectrums; but there too the limits quickly emerged. If a suicide drone takes a direct hitting trajectory on a target, even if it loses contact with its operator, it continues by inertia on exactly that straight line. If the target is stationary or extremely slow-moving (: artillery), it won’t escape.

On this issue, the issue of remote control, apart from defensive jammers (with which every military vehicle should be equipped from the hundreds on a front of over 1,000 kilometers; every other installation that could be a target; and every individual soldier…) other solutions began to be tested, “for and against” drones. One of these is equipping them with what tech fetishists want to call “artificial intelligence.” This involves “loading” their electronic part with images (from various angles) of their target types, so that they can identify them “on their own,” without needing guidance. In addition, these “smart drones” (!!!) are being tested in “herds,” either of simple type (launched in quantities, of the kind 100 or 200) or of complex type, with the ability to communicate and “exchange information” between them while flying…

Another “solution,” quite daring, that the Russian army used for the first time at Kursk involves drones (called Vandal) that are not guided via radio frequencies, but rather through… optical fiber!!! This is a Chinese idea. These drones are equipped with a spool of optical fiber that unfurls after takeoff as they fly; therefore, there is no possibility of jamming. It appears that Moscow’s technicians prepared this type (or copied the Chinese prototypes) for cases where frequencies have been completely “occupied” by the enemy. In the case of Kursk, however, the widespread jamming was a Russian operation (which essentially destroyed overall communications among the Ukrainian units that had invaded) – but the environment was the same: it was impossible for drones, friendly and enemy alike, to fly using radio-guidance. The related disadvantage? These fiber drones (which transmit a much clearer image from their cameras—an important factor for strike accuracy) cannot fly farther than the length of the optical fiber cable. So far, up to 10 kilometers.

Another development involves drones that are “launched” from combat aircraft (or from other drones/carriers): the thrust they gain this way increases their operational range. Ultimately, efforts are underway to develop drone-vs-drone systems: drones that either jam enemy communications in-flight or attack them directly—robotic air battles!

Machines against machines only?

The fact that these technological (and essentially techno-political) developments are taking place within a heavily ideologized cold war has, as a result, left them thus far as objects of militaristic analyses, almost exclusively. If the goal is to “crush Russia,” no one will concern themselves with how this will be accomplished; meanwhile, drones have over time evolved elsewhere as an advantage for Kyiv (to strike deep inside Russian territory) and elsewhere as an advantage for Moscow (on the main battlefield), if not for other reasons, certainly because it has a very large industrial, productive base that “exports” thousands of these devices continuously.

Consequently, whoever distinguishes the militaristic technological situation from this specific battlefield could conclude that the capitalist world has reached the point where wars will be fought mainly (or even exclusively in the future) between (opposing) machines. Particularly, the statement that “artificial intelligence” is used in these weapons (which are directed straight at humans) could lead to the shrill outcry that “machines now kill people on their own!” – the curse, the fear, and the mythology of “machine dominance.”

This is not the case, certainly not for what we described earlier. The “smart” drones, for example, those that have pre-installed images of the targets they seek, have the serious problem that they cannot distinguish “enemy” from “friendly” vehicles. The seriousness of the problem is highlighted by the fact that even without “automation,” with weapons directly operated by humans (tanks, airplanes…), there are very complex methods for making this distinction, which sometimes fail even then.

Drones have human operators! Human labor (destructive labor, in this case!) is important not only in the design and construction of these killing machines, but also in their operation. Especially this one: without skilled operators, drones can do very little.

The role of operators is so important that both Ukrainian and Russian sides have such highly valuable individuals, with many successes to their credit: a kind of skilled artillerymen or experienced saboteurs.

These operators are locatable. Difficult perhaps, but technically feasible: the exact coordinates of the signals transmitted to (or/and received from) the enemy’s drones must be found, taking into account that such an operator needs a space of 2 x 2 meters, or perhaps just a chair and a small table. Locating (and “neutralizing”) a skilled drone operator sometimes has the same significance as destroying a tank column: it is a force multiplier, and its neutralization often means the neutralization of the drones themselves (that he operates), even if they continue to exist in storage quantities!

This human labor (destructive work, we repeat) of “high productivity” (highly destructive…) is critical, and tends to approach (albeit from some easily understandable distance) that of military pilots: no matter how many warplanes one possesses, if one does not have capable pilots for them, one has nothing beyond scrap metal.

A part (the lesser-known side) of the drone war on the Ukrainian battlefield concerns exactly this: locating and “neutralizing” operators, especially the more experienced ones. Gaming, which one might assume is the great reservoir for this military specialty, doesn’t quite fit. The likelihood that while you’re targeting the enemy you yourself become a target is not the psycho-emotional environment of gamers. And having a bomb explode nearby, or seeing soldiers from your unit in pieces, is not what keeps your hand steady on, let’s say so, the drone controller, even if you (consider that you) are at a safe distance.

Although fully, 100% automated weapons systems remain the dream of the military industry and its executives under the conditions of the 4th industrial revolution, and although the prediction that “machines have become so smart that they have ‘freed themselves’ from humans and can eliminate them” always finds its audience, the way of “trust” has not yet been found that a (military) machine will never make a mistake when turning against “friendly” forces with the destructive power for which it was designed. Nor has any technology been found that guarantees the lasting monopoly of one side, and the inability of the other to hack it. Living labor (even in destruction), with all the organizational hierarchy that accompanies it, remains irreplaceable, to assume responsibility. The responsibility of “heroism,” or the responsibility of “error” (even “betrayal”)….

Ziggy Stardust

- The Ukrainians thought they found a “trick” to escape in such cases: as soon as they realize that a drone “sees” them, they fall to the ground and pretend to be dead!!! It is rare for the “trick” to succeed: usually they have been detected (alive) before they detect the threat, so they do not fool the enemy operator). The Russians, on the other hand, are trained to deal with an incoming drone with whatever means they have: with sudden changes in body posture, with karate moves… ↩︎