Introduction by the translator: Green technologies in a shade of… phosphorescent

Suddenly, nuclear technology seems to be going through a second youth. While until recently (and especially after the accident at Fukushima) nuclear power faithfully applied the doctrine of “learn by doing,” remaining hidden in the backyards of Western consciousness (and Western consciousnesses have, if nothing else, large backyards), in recent years it has been systematically and intensely promoted by the captains of the Western gallery. Why not, one might say, since the underlings continue to pull the oars without complaint?

Provided, of course, that the elites still consider it necessary (perhaps not for much longer) to provide some myths to their subordinates, the promotion of nuclear energy is not done without pretense. Every kind of justification has been mobilized, supposedly demanding their dynamic reintroduction into the energy mix – the model of hyper-mature capitalism, as it attempts to metastasize into the bio-informational model. Almost any official document one opens (and Wikipedia, for example, should be considered among these) now contains nothing but hymns to nuclear technology. How many human victims do we have per MWh of energy produced? Nuclear ranks at the very bottom of the relevant tables. How many victims from air pollution? Hydrocarbons, naturally, are at the top. Nuclear barely appears in the tables. And what is the carbon footprint of each energy source? It is, of course, understood that that of nuclear technology is orders of magnitude smaller than that of lignite and oil. After all this, one should not be surprised that nuclear is now considered even by decree as an ecological and green solution – perhaps it is neglected to mention here that the green of nuclear is slightly phosphorescent, but these are details for the subordinates of Western societies; it suffices for them to be able to discern shades on their new, high-definition screen.

So nuclear power, therefore, will save us from the climate crisis too. Of all the scars accumulated by Western societies, one of the most characteristic is their weak memory. Just a few decades have passed since images of a post-apocalyptic nuclear winter adorned the covers of magazines like Time and Newsweek. The fear then also concerned the climate, but the signs were reversed. Nuclear technology had come under the scrutiny (of which kind?) of criticism precisely because, in the eyes of the movements, it represented the archetype of the anti-environmental perception of the planet, constituting a global threat. The concerns about nuclear power back then were far more justified compared to today’s concerns about the “climate crisis.” The consequences of nuclear reactor accidents and atomic bomb detonations were far more documented; it would have taken many doses of willful blindness (of the kind that is now freely offered, with the help of tranquilizers, antidepressants, and cocaine) to deny them. Moreover, and equally importantly, it was absolutely obvious who (would) bear the absolute share of responsibility in case the worst happened; we were not dealing with carbon tones which somehow get produced somewhere and somehow get charged or credited to the right and left, to the extent that they even constitute a commodity or a stock exchange product.

Is it possible that scientific data has changed so dramatically that none of the above holds true anymore, and that this is the reason behind the recent communication revival of nuclear energy? No matter how much the performance of nuclear reactors has improved, their problems remain. Nuclear waste is not something you can simply bury in a landfill (although the Italian mafia might have a different opinion on this…). And as Fukushima recently demonstrated, accidents cannot naturally be ruled out. Given the nature (and physics) of this particular technology, it is difficult to imagine how the consequences of accidents could be controlled or even completely eliminated. When a few grams of a substance can produce enormous amounts of energy, the consequences of accidents involving this substance will almost inevitably be of a comparable scale. It seems to be a constant of technological development: the more energy a technology harnesses, the more devastating the consequences of its “misuse.” One might compare an aviation accident to a car accident, and to one involving horse-drawn carriages. In any case, nuclear technology has not achieved the technical leaps that would justify the recent shift in stance by Western leaders (nuclear fusion is not yet ready for mass application).

The reason behind this change, therefore, is more political in nature. The problem that the Western capitalist bloc has encountered concerns the increased energy needs that are expected to arise from the “electrification” of everything, at a time when access to traditional energy sources is not expected to be equally certain, given the ongoing decline of this bloc. The effort to detach the West from hydrocarbons may be partly true, but the motives behind it are certainly not as noble as they are presented. Political criticism against nuclear technology (and the fact that it is presented as the ideal solution to the energy problem) naturally has many more aspects which we cannot delve into here. Indicatively and only as an example, if gasoline-powered cars constitute such a curse for people, animals, nature (perhaps even for the galaxy itself), then why does replacing them with electric vehicles (which will be powered by electricity generated from nuclear sources) constitute a solution? Even if the problematic nature of cars is accepted, why shouldn’t criticism be directed generally against the logic of the internal combustion engine, with all the network of requirements, in terms of infrastructure, that it creates around it?

The magician’s act of presenting technical solutions to problems that are deeply political is, of course, nothing new. Those who have memory and judgment can easily understand that exactly the same thing happened in the case of the coronavirus. As the only “way out” from the “deadly” situation, the genetic vaccines of Moderna and Pfizer were presented, precisely with the logic that the solution to the problem had to be purely techno-scientific. Any other discussion that did not involve high biotechnology was excluded through summary procedures. And of course, the public believed that the magician was indeed Merlin the wizard.

The similarities, however, between nuclear and genetic technologies do not stop here. Another analogy has to do with how imperceptible the transition seems to be from political to military use of these technologies. It is known that genetics constitutes a basic tool in biological warfare research. Moreover, it is not at all unlikely that the coronavirus “escaped” from laboratories specifically specialized in such research. Maintaining the analogies, the same applies to nuclear technology. Atomic weapons no longer consist merely of bombs like those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. From depleted uranium bombs to tactical nuclear weapons and from there to strategic ones, there is an entire spectrum of such weapons, for every use. The political use of nuclear technology can “easily” be diverted toward military uses. And if at some point a “small” tactical nuclear weapon is actually used, it can naturally be justified under the pretext that it is a “calculated” use (regardless of whether some tactical nuclear weapons are now more powerful than the bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), necessitated by circumstances and by the need to save some other, allegedly higher good: the nation, democracy, lives that would otherwise have been lost, etc.

This was the pretext that the U.S. deployed when they decided to recklessly scatter the torches of their civilization, dropping the first atomic bombs on Japan: the overwhelming military advantage offered by these technological “achievements” would hasten the end of the war and thus save thousands of Japanese and American (primarily the latter!) soldiers’ (and civilians’) lives. Faced with this paradox of humanitarianism through the vaporization of entire cities, Christian squabbles over the filioque resemble monuments of common sense. The text we translate below systematically deconstructs this myth of American humanitarianism. Its author is the Canadian Jacques Pauwels, a somewhat eccentric historian who specializes in dismantling various historical myths constructed by the West. The following text is taken from his book The Great Myths of Modern History (The Great Myths of Modern History), and its original title is Mythmaking and the Atomic Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It shows in detail how more mundane and cynical were the reasons (reason of power is not always cynical, after all?) that ultimately led to the leveling of two Japanese cities. It is more than certain that, should such a nuclear episode be repeated, it will once again be wrapped in a heap of humanitarian flourishes (journalists, experts, and intellectuals must have something to do, after all). It is equally certain that a large percentage of subordinates will readily adopt such justifications. Perhaps texts like Pauwels’ may save a few from willful blindness and willing servitude.

myths about the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

After the German surrender in early May 1945, the war had essentially come to an end. The victors (the so-called Three Great Powers) now faced the complex and delicate issue of post-war reorganization of Europe. The U.S. had entered the war with significant delay, in December 1941. Their contribution to the victory against Germany was, in fact, quite limited until June 1944, when they began the landings in Normandy, that is, less than a year before the end of hostilities in Europe. However, when the war against Germany ended, Uncle Sam had secured a seat at the winners’ table, fully ready and eager to safeguard his interests and achieve his war objectives – it is a myth that he had a deeply rooted desire for isolation and simply wanted to withdraw from Europe: American political, military, and economic leaders had strong reasons to pursue a presence on the old continent. Similarly, Britain and the Soviet Union, the other two victorious great powers, attempted to secure their own interests. As was evident, none of the three could have everything their way and compromises would need to be made. In the eyes of the Americans, British expectations did not pose a particular problem; the same did not apply, however, to Soviet ambitions. So, what were the Soviet Union’s war objectives?

Being the country that had contributed far and away the most to the common victory against Nazi Germany, but at the same time suffered enormous losses, the Soviet Union had two major objectives. First, to secure substantial compensation from Germany for the incalculable destruction caused by German aggression, just as France and Belgium had demanded reparations from the Reich after the end of World War I. Second, to ensure security against future threats from Germany. These security issues also involved Eastern Europe, particularly Poland, which could serve as a springboard for German aggression against the U.S.S.R. For Moscow, it was imperative to ensure that it would never again in the future face hostile regimes in Germany, Poland, and the rest of Eastern Europe. The Soviets additionally expected their Western allies to consent to the reintegration of territories that Russia had lost during the revolution and the civil war, and to recognize the transformation of the three Baltic states from independent countries into autonomous republics within the Soviet Union. And now that the nightmare of war had ended, the Soviets anticipated that they could now continue the task of building a socialist society. As is known, the Soviet strongman, Stalin, deeply believed that “socialism in one country” was not only possible but also necessary, in contrast to Trotsky, who preached world revolution, hence their mutual hostility. What is less known, however, is that Stalin, as the war approached its end, had no intention of imposing communist regimes in Germany or in the other Eastern European countries that had been liberated by the Red Army. In France, Italy, and other countries of Western Europe that had been liberated by the Americans and their allies, he had even discouraged local communist parties from attempting to seize power. Already by 1943, he had officially ceased promoting world revolution, when he dissolved the Comintern, the international communist organization that Lenin had created in 1919 for precisely that purpose. It was a line that met opposition from many communists outside the Soviet Union, but satisfied Moscow’s Western allies, especially the U.S. and Britain. Stalin’s desire was to maintain good relations with them, as he needed their goodwill and cooperation in order to achieve the objectives mentioned above regarding reparations, the security of the Soviet Union, and its ability to continue building a socialist society. On their part, the American and British partners had never explicitly stated or even hinted that they considered Soviet expectations unreasonable. On the contrary, the legitimacy of Soviet war objectives had been repeatedly acknowledged, either directly or indirectly, in Tehran, Yalta, and elsewhere.

The Americans, together with the British, Canadians, and their other allies, had liberated most of Western Europe by the end of 1944. Moreover, they ensured that friendly regimes came to power in Italy, France, and other countries, even if these regimes were not so friendly toward their own citizens. Typically, this meant that local communists were almost completely marginalized. In cases where this was not possible, such as in France, the share of power granted to them was completely disproportionate to their role during the resistance and the extent of popular support they enjoyed. And although agreements among the allies stipulated that the “Big Three” would cooperate closely in managing and rebuilding the liberated countries, the Americans and the British refused Soviet involvement in cases such as Italy, the first country to be liberated already from 1943. The Americans and the British sidelined Italian communists, who were extremely popular due to their role in the resistance, favoring certain former fascists, such as Badoglio, and rejecting any Soviet participation. This modus operandi created a precedent of crucial significance. Stalin had no choice but to accept this arrangement, but, as American historian Gabriel Kolko notes, “the Russians accepted this solution without particular enthusiasm, but they would not forget it in the future and would use it as a precedent – the Soviets undoubtedly had a say in Italian matters, since Italian armies had participated in Operation Barbarossa” (which invaded Russian territory).

During the period 1943-1944, the American and British liberators acted at will in Western Europe, ignoring not only the desires of a large part of the local population, but also the interests of their Soviet ally, with Stalin accepting this condition. When 1945 came, however, the situation had reversed: the Soviets had a clear advantage in Eastern Europe, which the Red Army had liberated. Nevertheless, the Western allies hoped that they might somehow manage to participate in the reorganization of this part of Europe as well. Everything was still possible there. The Soviets obviously favored the local communists, without having created definitive outcomes yet. For their part, the Western allies knew very well that Stalin counted on their good will and cooperation, and that therefore he would be willing to make concessions. The political and military leadership in Washington and London believed that Stalin had every reason to be conciliatory towards them, fearing the potential consequences otherwise. The Soviet leader had a clear awareness of how tremendous his country’s achievement was in emerging victorious from the battle to the death with the Nazi monster. However, he also knew that several within the American and British leadership, primarily Patton and Churchill, harbored deep hatred for the Soviet Union, to the point of even contemplating the possibility of a war against it immediately after the defeat of their common enemy Germany, preferably with a march towards Moscow, embracing Nazi remnants; the plan, called Operation Unthinkable, was Churchill’s brainchild. Stalin had every reason to want to avoid this scenario.

The Soviet views regarding possible reparations and their security were not unreasonable at all; the British and American leadership had recognized their legitimacy, either directly or indirectly, during a meeting of the Three Great Powers in Yalta in February 1945. Nevertheless, Washington and London did not view favorably the possibility that the Soviets would receive what was due to them after all the sacrifices they had made and the effort they had exerted in the name of the common anti-Nazi struggle. The Americans in particular had their own plans regarding both post-war Germany and Eastern and Western Europe in general. For example, reparations might give the Soviets the opportunity to successfully continue the work of building a communist society, a system opposed to the international capitalist system of which the U.S. was the undisputed leader.

What Uncle Sam primarily sought for Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe was to impose governments, democratic or not, that would follow a neoliberal economic policy of “open doors” for American products and investment capital. While Roosevelt had shown some understanding toward the Soviets, after his death on April 12, 1945, Harry Truman, who succeeded him, had no inclination to recognize or understand the Soviet side. Both he and his advisors abhorred the idea of the Soviets receiving significant reparations from the Germans, since such a move would automatically exclude the possibility of transforming Germany into a profitable market for American products and investment capital. Moreover, they considered it unthinkable that the Soviets would use German money to build a socialist system that would clash with capitalism.

The Soviet proposals were absolutely reasonable, and Soviet leaders, including Stalin (who is often mistakenly believed to have made all decisions single-handedly), intended to proceed with serious concessions. There was room for dialogue with them; however, such dialogue required the Western powers to show patience and understanding toward the Soviet position and to accept the fact that the Soviet Union had no intention of leaving any negotiations empty-handed. Truman, on the other hand, had no desire to engage in such dialogue – the fact that Stalin’s interest in dialogue was genuine and that he did not have unreasonable demands would later become evident in the postwar arrangements for Finland and Austria; when the time came, the Red Army withdrew from these countries without leaving behind any communist regime.

Truman and his advisors hoped that they would eventually force the Soviets to abandon their demand for German reparations and that they would withdraw not only from eastern Germany but also from Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe. In this way, the Americans and the British would be free to act in these regions as they had done in Western Europe. Truman further hoped that he could push the Soviets to put an end to their communist experiment, which still served as a source of inspiration for various “red” radicals and revolutionaries around the world, even within the U.S.A.

In the spring of 1945, Churchill had floated the idea of a joint American and British military operation, together with Nazi remnants, against Moscow. However, this plan, named Operation Unthinkable, was ultimately abandoned, mainly due to opposition from military personnel and civilians, as had also been the case with the possibility of armed intervention in the Russian civil war. Truman was probably disappointed by this development, as Patton probably would have been as well, who expected to play a crucial role once again. However, on April 25, 1945, just a few days before the German surrender, he received shocking news. He was briefed on the highly classified Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb, or S-1, as it was codenamed. This new and powerful weapon, on which the Americans had been working for years, was nearly ready, and if the tests were successful, it would soon be available for use. Truman and his advisors seemed suddenly enchanted by a “vision of omnipotence,” as distinguished American historian William Appleman Williams called it. They were now convinced that this new weapon would allow them to impose their will on the Soviet Union. For Truman, the atomic bomb was a “hammer” that he could wield threateningly over the heads of “those boys in the Kremlin.”

Thanks to the bomb, it!! seemed a! possibility forcing Moscow to withdraw the! Army from Germany and to ignore Stalin on issues of postwar arrangements. Moreover, it now seemed! to install! or even anti!unist regimes in Poland and other countries! eastern Europe and to! the possibility of! in them. Indeed, from the mind of some! even the! that the Soviet Union would become receptive not! only! investment capital! also general American political! economic influence and that this heretical country would return to!om of global capitalist church. As writes the German historian Jost Dülffer,! ” are indications that! believed that the! of atomic! would serve as a passport for the!.S.A.! and plans for a! new order. Indeed having the atomic gun in his! the American president did not!! to behave towards the boys of! as equals him since! they not possess! such such super-!. Gabriel!ko writes! “the American leadership! in condemning Russia and refused to negotiate seriously! simply because as an economic and military! excessive self-confidence felt that it! define the new!.

! /wp:paragraph –>The possession of such a powerful new weapon revealed new possibilities in relation to the ongoing war in the Far East and the post-war arrangements that would take place there, which were of crucial importance to the American leadership. Nevertheless, the bomb first had to be successfully tested and available for use before this ace was pulled from the sleeve of the U.S. Therefore, Truman did not need Churchill’s advice during his discussions with Stalin about the immediate future of Germany and Eastern Europe, even “before the armies of democracy melt away,” that is, before American forces withdrew from Europe. Ultimately, Truman agreed to a summit meeting of the Three Great Powers in Berlin, but not before summer, when the bomb was expected to be ready.

The meeting eventually took place from July 17 until August 2, 1945, not in the bombed Berlin, but in nearby Potsdam. There, Truman finally received the long-awaited message that the atomic bomb had been successfully tested on July 16 in New Mexico. Feeling sufficiently strong, he could now make his moves. He was no longer interested in presenting realistic proposals to Stalin, but only in raising all sorts of non-negotiable demands; at the same time, he summarily rejected all proposals from the Soviet side, such as those concerning German reparations. Stalin, however, did not yield, even when Truman attempted to intimidate him, whispering in his ear that the U.S. now possessed a powerful new weapon. The Soviet leader, who surely must have been informed about the Manhattan Project by his spies, remained expressionless and silent. Truman concluded that only a real demonstration of the atomic bomb would ultimately persuade the Soviets to yield. As a result, no agreement on significant issues was achieved at Potsdam.

Meanwhile, the Japanese continued to fight in the Far East, despite being in a desperate situation. They were not opposed to the possibility of surrender, but not unconditionally, as the Americans demanded. In the eyes of the Japanese, an unconditional surrender could result in ultimate humiliation: forcing Emperor Hirohito to abdicate and stand trial for war crimes. The American leadership was fully aware of the situation, and some within it, such as James Forrestal, Undersecretary of the Navy who oversaw the naval forces, believed, as historian Gar Alperovitz writes, that “a statement assuring the Japanese that unconditional surrender would not involve the dethronement of the emperor would bring a definitive end to the war.”

Unconditional surrender was by no means an urgent demand that could not be circumvented; moreover, on May 7, at General Eisenhower’s headquarters in Reims, the German request for a delay in the ceasefire for at least 45 hours had been accepted, a period that would allow a large portion of their armies to escape from the eastern front to fall into the hands of the Americans and British rather than the Soviets. Even at this final stage of the war, many of these units remained on standby (with their weapons, uniforms, and under the command of their own officers) for potential use against the Red Army, as Churchill himself admitted after the war. Therefore, a Japanese surrender was clearly within the realm of possibility, despite Japan’s request for asylum for Hirohito. Ultimately, the condition set by Tokyo was anyway insignificant. After Japan’s unconditional surrender, the Americans did not even bother to bring charges against Hirohito, and it was only thanks to their own support that he managed to remain emperor for several more decades.

For what reason did the Japanese believe they had the luxury of setting terms regarding their surrender? The reason was that the main body of their forces in China remained intact. They considered that they could use these armies to defend Japan and that in this way they would force the Americans to pay a heavy price for their inevitable final victory. However, it was a plan that could only succeed if the Soviet Union did not get involved in the Far Eastern front, which would force the Japanese to maintain large forces in mainland China. Therefore, it was Soviet neutrality that gave Japan some hope; not hope of victory, of course, but hope that Washington would eventually accept their term regarding the Emperor. The reason the war with Japan was dragging on was, to some extent, the fact that the U.S.S.R. had not become involved in it. Nevertheless, Stalin had already promised since 1943 that he would ultimately declare war on Japan within three months after the German surrender, a promise he had repeated on July 17, 1945, at Potsdam. Consequently, Washington was expecting a Soviet attack against Japan in early August. It knew very well that the Japanese were in a desperate situation. “Once this happens too, the Japanese are finished,” Truman would write in his diary, referring to the expected Soviet intervention in the Far East.

Moreover, the American navy reassured Washington that it was in a position to prevent movements by the Japanese intending to transport troops from China back to their homeland in order to assist in the defense against an American invasion. Ultimately, it was questionable whether an American invasion of Japan would even be necessary, since the powerful American fleet could simply proceed to blockade the Japanese islands and thereby bring the Japanese face to face with the dilemma of either surrendering or dying of starvation.

Truman therefore had many alternatives if he wanted to end the war against Japan without being forced into further sacrifices. Initially, he could have accepted the Japanese insignificant term for granting asylum to their emperor. He could have waited until the Red Army attacked the Japanese in the China region, forcing Tokyo to accept an unconditional surrender. Finally, he could have proceeded with a naval blockade of Japan, something that would force it to surrender sooner or later. Truman and his advisors rejected all these alternatives. Instead, they chose to take Japan out of the battle with the atomic bomb.

This fateful decision, which would cost the lives of hundreds of thousands, mostly ordinary citizens, offered, on the other hand, some important advantages to the Americans. First, there was the possibility that the bomb would force Tokyo to surrender before the Soviets became militarily involved in Asia. In this case, there would be no reason to allow Moscow to participate in decisions regarding post-war Japan, the territories it had occupied (e.g., Korea and Manchuria), and more broadly, East Asia and the Pacific region. The U.S. would thus have the opportunity to gain absolute hegemony over this part of the world, which constituted the real, albeit not publicly declared, purpose of Washington in its conflict with Japan. For this very reason, the option of a naval blockade was rejected: it would take months before Japan would surrender, giving the Soviet Union time to enter the war.

The risk of a Soviet intervention in the Far Eastern war was that the Soviets would gain the same advantage that the Americans had gained from their own, relatively delayed, intervention in the European war—namely, the right to participate in discussions and decisions regarding the fate of the defeated enemy, new borders, and post-war socio-economic and political structures. This would grant them enormous prestige and other benefits. Washington did not want the Soviet Union to gain such a right under any circumstances. Having first neutralized their major imperialist rival on this side of the globe, the Americans had no intention of facing a new adversary, whose communist ideology, among other things, was finding increasingly receptive ears in many Asian countries, including China. The use of the atomic bomb would give American leadership the opportunity to end the war with Japan more quickly and to begin reorganizing the Far East without the participation of the troublesome Soviets.

The atomic bomb offered American leadership yet another significant advantage. After the meeting at Potsdam, Truman was convinced that only a demonstration of this new weapon under real conditions would make Stalin more conciliatory. The leveling of a Japanese city with the atomic bomb seemed to be the perfect maneuver to intimidate the Soviets and force them into generous concessions regarding post-war arrangements for Germany, Poland, and other countries in Central and Eastern Europe. James F. Byrnes, Truman’s Secretary of State, is said to have later declared that the atomic bomb was used with the purpose of serving as a show of strength that would make the Soviets more accommodating on European issues.

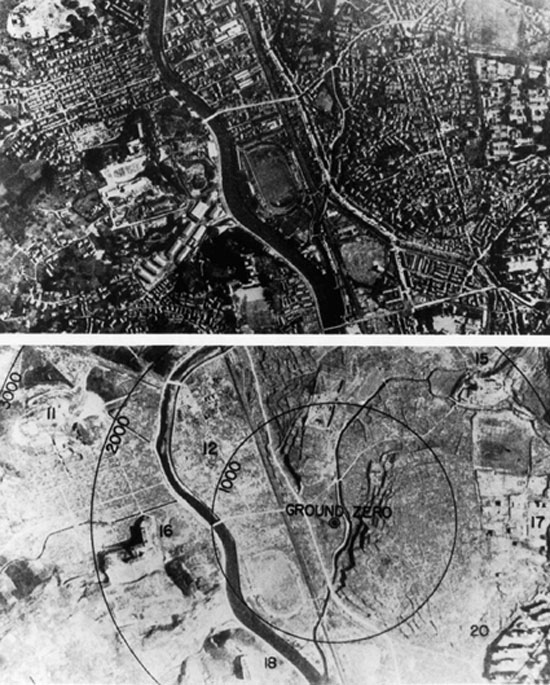

Since the desired goal was to terrorize the Soviets (and the rest of the world), then obviously the bomb should have fallen on a large city. Most likely for this reason Truman rejected the proposal of some scientists from the Manhattan Project to demonstrate its power by dropping it on an uninhabited Pacific island: the destruction and death would not have the necessary extent. The other problem was the possibility of humiliation of the Americans, in case the bomb did not work as expected and suffered some damage. Such a failure of the bomb would pass, on the other hand, unnoticed if it fell unexpectedly and without prior announcements on some Japanese city. A large Japanese city had to be found, but not Tokyo, which moreover was already flattened by previous conventional bombings, with the result that there was a possibility that any additional destruction from the atomic bomb would not seem impressive enough. Very few cities were sufficiently “virgin” for the atomic bomb. The reason; At the beginning of August 1945, only ten cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants remained relatively untouched by the bombings, with several of them being out of bombing range (due to the non-existent Japanese air defense, the bombers had begun to destroy cities with fewer than 30,000 inhabitants). Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not have this luck.

The construction of the atomic bomb was completed at exactly the right time, before the Soviet Union could get involved in the Far East. Hiroshima was flattened on August 6, 1945, but the Japanese leadership did not immediately offer an unconditional surrender. The reason was that the scale of the destruction was naturally large, but not larger than what previous air raids on Tokyo had caused, such as those on March 9 and 10, 1945, when thousands of bombers caused more destruction and deaths than the “virgin” atomic attack on Hiroshima. This development somewhat disrupted Truman’s plans. On August 8, 1945 (exactly three months after Germany’s surrender in Berlin), even before Tokyo capitulated, the U.S.S.R. declared war on Japan, and the next day the Red Army launched an attack against Japanese forces in northern China. From that point on, Truman’s and his advisors’ goal was to end the war as quickly as possible in order to limit, to some extent, the “damage” (as they perceived it) caused by Soviet intervention.

On August 10, 1945, just one day after the Soviet Union entered the war in the Far East, the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Regarding this bombing, in which many Japanese Catholics also perished, an American, a former military chaplain, had made the following statement: “I think that’s a reason they dropped the second bomb. To speed things up. To force them to surrender before the Russians arrive” (this chaplain perhaps did not know that among the 75,000 human beings who were “instantly incinerated, carbonized, and vaporized” in Nagasaki, there were also several Japanese Catholics, as well as an unknown number of Allied prisoners of war held in camps, whose presence was known to the air force command, without this fact moving them).

The reason Japan surrendered was not the atomic bombs, but the entry of the Soviets into the war. After the complete destruction of so many major cities, the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however horrific it may seem, did not hold great significance from a strategic perspective. However, the Soviet declaration of war dealt a fatal blow, as it ruled out any hope that Tokyo might submit even some minor conditions in its inevitable surrender. Moreover, the Japanese leadership knew that it would take months before American forces could land in Japan, despite the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Red Army, on the other hand, was advancing so rapidly that it was estimated to cross into Japanese territory within ten days. In other words, due to Soviet involvement, Tokyo was left without time, and without alternatives beyond unconditional surrender. Japan surrendered because of the Soviet declaration of war, not because of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even without the atomic bombs, the Soviet entry into the war would have been sufficient to lead Tokyo to surrender. The Japanese leadership, however, needed a little time. The official surrender took place on August 14, 1945.

The remarkable progress of the Red Army during these final days of the war caused great displeasure in Truman’s circle. The Soviets had even begun to expel the Japanese from their Korean colony, collaborating with a Korean liberation movement under the leadership of Kim Il-sung, which proved extremely popular and was therefore destined to take control of the country after its liberation from the hated Japanese colonial yoke. However, the prospect of an independent socialist Korea was not within American plans for the post-war Far East. Washington hurried, therefore, to send troops to occupy the southern part of the peninsula, with the Soviets agreeing to a division of the country which was supposedly temporary, but ultimately lasts until today.

As things stood, the Americans would eventually be forced to burden themselves with their Soviet allies on matters concerning the Far East, but Truman took care to prevent this possibility. He refused to accept that the previous cooperation of the three great powers in Europe had created any precedent, and thus rejected Stalin’s request on August 15, 1945, for a Soviet occupation zone within the defeated land of the rising sun. Moreover, during the surrender ceremony of Japan on September 2, 1945, aboard the American battleship Missouri, which had anchored in Tokyo Bay, representatives of the Soviet Union and other allies, such as Great Britain and the Netherlands, were allowed to be present, but only as minor attendants. Japan was not divided into occupation zones, as was Germany. Only the Americans would have rights over it. General MacArthur, as the American viceroy in Tokyo, made sure that no other power would have a say in the issues of post-war Japan, regardless of how much it had contributed to the joint victory against her.

The American conquerors reorganized the land of the rising sun according to their own ideas and interests. In September 1951, the U.S., now fully satisfied, would finally sign a peace treaty with Japan. The U.S.S.R., on the other hand, whose interests had not been taken into account at all, did not sign it. The Soviets withdrew from the areas they had liberated in China and Korea, but refused to withdraw from Japanese territories, such as Sakhalin Island and the Kuril Islands, which had been occupied by the Red Army during the final days of the war. The Americans would later harshly criticize them for this stance, behaving as if their own stance had nothing to do with that of the Soviets.

The American leadership believed that, after the rape of China by the Japanese, after the humiliation of the great, traditional, colonial powers, such as Great Britain, France and the Netherlands, and after its own victory over Japan, all that remained for it to realize its dream of absolute sovereignty in this part of the world was the exclusion of the U.S.S.R. from the Far East, something that seemed almost certain. When China was “lost”, falling into the hands of Mao’s communists after the war, their disappointment and displeasure intensified even more. Things got even worse when the northern part of Korea, a former Japanese colony which the U.S.A. aspired to convert, along with Japan, into a subordinate state to them, decided to follow its own, idiosyncratic path towards socialism; while in Vietnam a popular independence movement under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh also envisaged a future for his country that was incompatible with the grandiose ambitions of the U.S.A. The wars in Korea and Vietnam were therefore no surprise. The U.S.A. almost became involved in armed conflict even with “red China”.

For Japan’s surrender, it was not necessary to use atomic bombs. As an in-depth American study would later admit, “it is certain that Japan would have surrendered before December 31, 1945, even if the atomic bombs had not been used, even if Russia had not entered the war, even if there were no plans for an invasion.” The same concession has been made by many in the American military leadership, including Henry “Hap” Arnold, Chester Nimitz, William “Bull” Halsey, Curtis LeMay, and even future President Dwight Eisenhower. Nevertheless, Truman insisted on using the bomb for various reasons, not merely to force the Japanese to surrender. His goal was to keep the Soviets away from the Far East and to intimidate their leadership so that Washington could impose its will on European issues. For these reasons, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were reduced to dust. Not a few American historians know well what happened. Sean Dennis Cashman writes: “As the years have passed, many historians have now concluded that the bomb was used for political reasons… Vannevar Bush (head of the American Office of Scientific Research and Development) declared that the bomb ‘was ready for delivery at exactly the right time so that concessions to Russia would not be necessary after the end of the war.’ Secretary of State (under Truman) James F. Byrnes never denied a statement attributed to him according to which the bomb was used as a demonstration of American power toward the Soviet Union so that it would become more accommodating in Europe.”

Truman himself, however, hypocritically declared at the time that the purpose of the two nuclear bombings was “to bring our boys back from the front,” that is, to quickly end the war without further sacrifices from the American side. The American media promoted this explanation without any critical disposition, and thus the relevant myth was created, with the help of historians of his camp, both in the U.S. and more broadly around the world, but also with the help of Hollywood.

The myth that two Japanese cities were bombed with nuclear weapons in order to force Tokyo to surrender and thus shorten the war and save lives is a myth that bears the made in U.S.A. seal. However, it was readily accepted even in Japan, whose leaders after the war, acting as vassals of the U.S., found something very useful in it. Firstly, the emperor and his ministers, who bore considerable responsibility for a war that had brought so much misery to the Japanese people, could shift the blame for their defeat onto this “astonishing scientific achievement that no one could have foreseen.” Behind the blinding light of the atomic explosions, they could hide their own mistakes and omissions. The Japanese people had heard many lies about the critical nature of the situation at the front and about how much they had to suffer simply and solely to save the emperor. The bomb, however, provided the perfect excuse for the defeat. No one needed to be accused or take responsibility, and no investigatory tribunal needed to be set up. Japan’s leaders were able to claim that they had done their best. And so the bomb was used to deflect any blame away from the Japanese leadership.

Secondly, the bomb whitewashed Japan’s international solidarity. Like Germany, Japan had conducted an aggressive war, committing a multitude of war crimes. It was important for both these countries to find a way to improve their international image, shedding the mantle of the perpetrator and wearing that of the victim. This logic was followed after the war by West Germany, inventing the myth of the red army, which poured into Berlin with the momentum of a horde of racially inferior Mongols, raping blonde Fräuleins along the way and looting any graphic art it encountered. In the same way, Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave Japan the opportunity to present itself as a victimized nation, a nation that had suffered an unjust attack with an inhuman and terrifying weapon of war.

Thirdly, by repeating themselves as mouthpieces that the bomb had hastened the end of the war, the Japanese ensured that their American overlords remained satisfied. In turn, these latter would ensure to provide protection for the upper Japanese classes against demands for drastic social changes, such as those expressed by radical elements, including communists who had great resonance among the poorer Japanese strata with their threats against the plutocracy. But for a long time, the Japanese elites worried that the Americans might abolish the institution of the emperor and try many government officials, bankers, and industrialists for war crimes. They therefore had every reason to please the Americans. As a Japanese historian has written, “If they wanted to believe it was the bomb that won the war, why should we spoil it for them?” The Japanese acceptance of the Hiroshima myth gave the Americans the opportunity to cultivate, both in Japan and the rest of Asia, the image of a militarily all-powerful but ultimately peace-loving state, which would exploit its monopoly on the atomic bomb only if absolutely necessary. As Ward Wilson points out:

“If, on the other hand, the Soviet entry into the war was what would force Japan to surrender, then the Soviets could claim that they achieved in four days what the U.S. did not achieve in four years, which would lend prestige to the Soviet army and Soviet diplomacy. Since the Cold War had already begun, accepting that the Soviet entry was the decisive factor that ended the war would be tantamount to offering aid to the enemy.”

Over time, the myth that the nuclear bombing of two Japanese cities was justified has lost much of its favor on both sides of the Pacific. In 1945, 85% of Americans shared this view, but the percentage dropped to 63% in 1991 and to 29% in 2015. Among the Japanese, 29% agreed in 1991 and only 14% in 2015. It was evident that the myth needed a boost, something that was done by one of Truman’s successors, President Barack Obama.

Obama visited Hiroshima in May 2016. In a public speech, he described the leveling of the city by the atomic bomb in 1945 in a calm tone as “death falling from the sky,” as if it were hail or some other natural phenomenon with which his own country had nothing to do, and avoided uttering even a single word of remorse or apology on behalf of divine Sam. The New York Times, in an enthusiastic report on this presidential performance, wrote that “many historians believe that the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which cost the lives of more than 200,000 people, ultimately saved more lives, since an invasion would have caused much greater bloodshed.” The fact that there are many events that contradict this “belief” and that many historians believe the exact opposite was not even mentioned. This is how myths are kept alive, even those that are on their last legs.

Translation, adaptation:

Separatrix