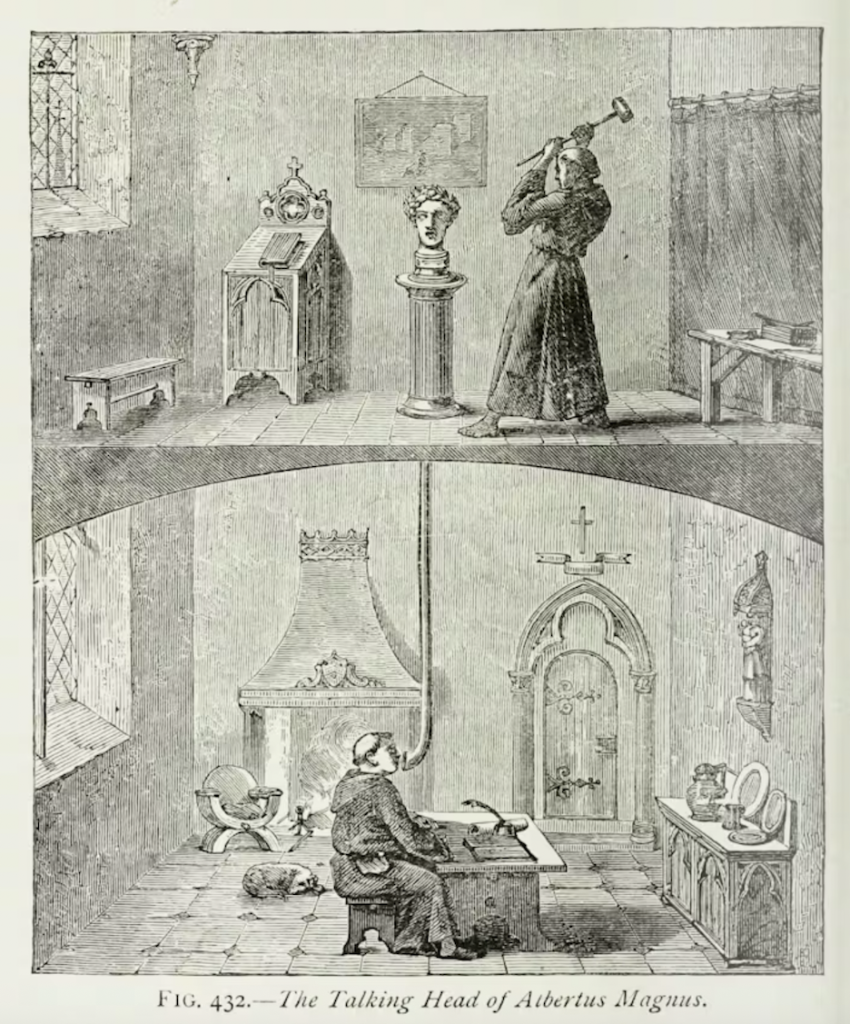

A 15th century tale, originating from Alfonso de Madrigal, a prolific 15th century commentator who enjoyed creating stories with moving statues in the Middle Ages, wants Albertus Magnus, a real person, a Dominican monk, theologian and philosopher who lived two centuries before Alfonso, in the 13th century, to have managed to compose a whole man out of metal. According to de Madrigal, Albertus needed 30 years for this work, but he succeeded. His automaton answered even the most difficult questions, solved even the most serious problems; while, according to one variant, it had dictated a large part of Albertus’s bulky writings to him. According to Madrigal, Albertus’s metallic man met his fate at the hands of Thomas Aquinas, Albertus’s student, who dismantled him, tired of his “endless babbling.”

An old story or, more accurately, one of the many old stories concerning the fascination and attraction that the idea of the machine that knows, the machine that speaks had on the educated circles of illiterate societies. But something remained (beyond the obvious similarity of this fascination / attraction then and now…) and a word. Gabriel Naude, a French doctor and encyclopedist, personal physician to the French king Louis the 8th, reviewing the legend of Albertus Magnus described his mythical creation in 1625 as “androides”. It was a new word…

Not all of these would be worth permanent prices, Albertus Magnus, Alfonso de Madrigal, and Gabriel Naude in our days. Shouldn’t Google’s bosses pay for the name of their Android?

The destruction of Magnus’s “speaking head” as a lie by Akinites: this was the view of the “encyclopedic simplification of science” of J. H. Pepper in 1885