Always look at the bright side of life…

It’s 7:59 in the morning on some weekday and you’re enjoying your sleep. In a minute, the smart watch you recently bought is about to wake you up with the sounds of some indie, honeyed melody (here we assume you’re so obsessive as to set your alarm for round hours). The mechanical hand of the watch, which of course above its electronic intelligence owes a vintage aesthetic, moves to the next minute, but no sound comes out. No, the watch hasn’t broken. It’s just so smart it has calculated how many hours you’ve slept and can tell from your heartbeat that you’re in some deep stage of sleep. So, for your own good, it “decides” to give you another hour of sleep. When it finally wakes you up somewhere around nine something and immediately as you get out of bed, it sends a signal to the smart lights in your house to turn on automatically. And these are so smart that through your posts on facebook, they can calculate your mood, which isn’t that difficult in cases of lovesickness. A soft, sensual light fills the room, while the coffee maker also receives a signal to start preparing your coffee. Of course, the smart water heater has brought the water to the proper temperature. A little later, as you drive to work, your smart car (which probably won’t even need a driver), based on your music preference history, automatically plays a new song it believes you’ll like. Naturally, you’re jamming along when suddenly you feel a “hug” from your smart jacket. One of your posts on facebook received a like and your jacket, which is of course connected to the internet, is set up to “hug” you with every like.

…

[A few hours later]

…You’ve just finished work and you’re getting into your (smart, let’s not repeat ourselves) car. You place your thumb on the recognition scanner to start it up and ask it to find you a seaside restaurant with a view, and to make a reservation for a romantic dinner right at sunset. The car’s “brain” begins the search, but here the smartwatch intervenes to inform you that, based on your activity today, you haven’t burned the necessary calories to stay in good physical shape. It suggests you go to the gym, but you insist on dinner. The search continues until the watch intervenes again, reminding you that if you skip the gym, you risk not reaching your distance goal on the treadmill. And if you don’t reach it, you’ll lose your annual discount and at exactly 12:00 midnight, double the amount will automatically be charged to your account. It suggests a compromise: go to the gym now for the remaining 23 kilometers and postpone dinner. You agree, slightly annoyed, it’s true.

You’ve already run the first 5 kilometers, and amid the wheezing and sweat, you wonder how you’ll manage the remaining 18 and whether you’ll have the energy for anything else beyond drying off and falling asleep. At least your attention is diverted by the attractive girl who got on the treadmill right across from you. Your smart glasses identify her, pull information about her from the internet, and the compatibility app you’ve downloaded informs you that you have a high compatibility score. So you straighten up and try not to look like a disheveled soldier on parade, hoping to impress her. But 6, 7, 8… the kilometer counter climbs torturously slowly and you’re about to lose your breath. A break and some water would save you. Except your legs are so numb from exhaustion that you stumble as you step off the treadmill and take a spectacular fall. The app notifies you that this embarrassing incident just drastically reduced your chances of getting a response from the girl.That was it. You leave the gym and hurry up for the certainty of a romantic dinner. Despite the car’s warnings that you have exceeded the speed limit, you keep pressing the gas pedal a little more to make it on time, while at the same time trying to figure out exactly where the GPS indicates you are. A tremor in the steering wheel brings you back. Strange, but you ignore it. Except that at the next turn, the car doesn’t seem to turn no matter how much force you apply. Before it hits the divider, it suddenly brakes hard in the middle of the road on its own. And then starts abruptly again. And brakes again… Until the following truck takes you along for a trip to the other world. As you lie crushed among the car’s wreckage, the screen displays a message: “You got owned! Sri Lanka hacker warriors for evah, dude!”. Thank God, the smartwatch realizes you’re in your final moments and sends a signal to the insurance company, which immediately informs your family of the amount they are entitled to. It’s a relief to know that a good life insurance eventually paid off. At least you won’t make it to the courtroom, where the insurance company will claim that, based on data from the car’s black box, exceeding the speed limit constitutes a breach of your policy terms…

In the previous issue of Cyborg we made an extensive reference to the smart cities of the future. In case you didn’t understand, the above fictional story we concocted1, is a fragmentary description of the smart future… in general, at least as envisioned by engineers, scientists, governments, companies, even international organizations. In their articles and reports they often employ this rhetorical device of narrating a day in the life of a future citizen, but it is understood that the narrative includes only the idyllic (for some, at least) situation of the first paragraph. Welcome to the Internet of Things, or IoT as it has been established.

A brief history

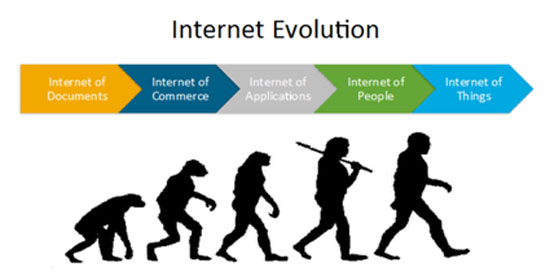

Until quite recently, the dominant image that came to mind when hearing the word Internet included a specialized and relatively expensive device, the computer, whose user had to sit in front of it and dedicate a portion of their time in order to connect with other, even more expensive computers, to find the information they were seeking or to communicate with other users. From a spatial perspective, computers constituted something like furniture in an urban household, occupying their own space and requiring not only the user’s presence, but also their active participation. Moreover, from a temporal standpoint, what was considered “time in front of the computer” formed a distinct field of temporal order. The device (like so many others in the past) could not function unless the user specifically dedicated time to it. In recent years, as computing devices become increasingly smaller, from laptops to mobile phones (which are only abusively and out of habitual inertia still called phones), with their cost decreasing over time, the perception of them as spatiotemporally compact points with their own rules appears increasingly outdated.

For supporters of the Internet of Things, this development represents a natural trend in information technology. In fact, it’s not just a natural trend—it has already been delayed in delivering its true benefits. There is still another characteristic of these devices that poses obstacles to unleashing their inherent potential—and to moving toward a technological utopia. And that is nothing else but the fact that they still remain… devices. The real revolution will come at the moment when every object in our technical and natural environment, from a coffee cup and underwear to biological organs themselves, will have the ability to incorporate the computing and networking technology that today’s specialized devices possess for this purpose. Every object should become a device, without giving the impression of a device that requires handling. Being interconnected, they will be able to “communicate” both with each other and with users, without the communication barriers imposed by the need for special handling.

“The technologies with the deepest impact are those that end up disappearing. They become so interwoven into the fabric of daily life that they ultimately become inseparable from it.”

Mark Weiser, The Computer for the 21st Century, Scientific American, September 1991.

(One could claim exactly the same for ideology of course…)

With these words, Mark Weiser begins his most famous article, “The Computer of the 21st Century.” Written in 1991 (yes, a quarter of a century has passed since then), before the full commercial liberalization of the internet, when it was still under the supervision of the American government, and just a short time after Tim-Berners Lee had designed the World Wide Web, the aforementioned article has since become something of a manifesto of the so-called ubiquitous computing2. A term that is nothing more than the then rendering of the Internet of Things.

The reason we are referring to this particular article, beyond any historical value it may have, is twofold. First, due to the date of its publication. What today seems advanced and bordering on science fiction draws its origins from discussions and ideas that circulated among scientists (and not only) in earlier times, when it would have been even more difficult for someone to conceive such scenarios. This, of course, does not make Weiser a prophet. However, technological developments and their outcomes constitute, to some extent, self-fulfilling prophecies. To put it differently, such developments, beyond any inherent momentum they may have, do not appear suddenly, as if falling from the sky. At critical junctures, they require deliberate (or more often semi-conscious) decisions that ultimately boil down to political choices. Second, and in contrast to other graphic examples that indulge in essentially metaphysical quests and unattainable scenarios driven purely by ideological purposes (such as the possibility of post-mortem life through brain digitization), Weiser seems to have had much firmer grounding in reality. As the head researcher at Xerox PARC, a research center with a history of concrete and highly practical results (the simplest being the graphical user interface of computers, without which their mass adoption would have been impossible), he possessed both the knowledge and the necessary connection to reality to make realistic projections about the future. Even if the rhetoric, both of himself and his successors, resorts to an idyllic imagery (and it could hardly do otherwise) that resembles that of traveling salesmen and directly competes with television advertisements in terms of exaggeration, in the aspect of practical applications—and regardless of their consequences and implicit assumptions—it probably hit the mark.

For the sake of truth, in 2005 the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) decided to dedicate its annual exhibition specifically to the Internet of Things. This particular Union is nothing less than the United Nations agency that specializes in telecommunications matters.3 And if anyone needs numerical confirmation, they can look up the funding that the EU intends to allocate for the Internet of Things through its new research funding program, Horizon 2020.4 Just one of the research directions that emerge after searching with the term Internet of Things gives us an amount of 586 million euros. And if this amount still seems small compared to the total 80 billion of Horizon 2020, feel free to become populists and search, for the sake of comparison, for research programs with other keywords (for cancer, we say now…).

The Internet of Things: the end of capitalist production or its universal diffusion?

Beyond the absolute economic magnitudes however, the wonderful new world that the Internet of Things promises to bring seems to also have some other economic implications, as far as the structure of production itself is concerned. According to some of its supporters, the new Internet will bring about, neither more nor less, the end of capitalism, as we have known it for a few centuries now. One of the most fervent adherents of this view – prediction is the well-known Jeremy Rifkin.5 His latest book, which was published just last year (2014), bears the very modest title The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism (Η Κοινωνία του Μηδενικού Οριακού Κόστους: Το Διαδίκτυο των Πραγμάτων, τα Συνεργατικά Κοινά και η Έκλειψη του Καπιταλισμού. Any similarities with Negri and Hardt are not at all coincidental).

Risking being somewhat tiresome, we will try to reconstruct its central argument, to the extent that we have understood it.6 What in classical economics is called marginal cost refers to the cost of producing one more unit of a specific product. This particular measure is considered especially significant for the simple reason that it does not remain constant. Producing the first keyboard from a company has a high cost simply because capital must be invested to build the factory. Naturally, the second keyboard will have a lower marginal cost. Theory predicts that, under conditions of open markets and free competition, marginal cost tends to decrease until it reaches a low point, after which it begins to rise again. If consumer demand is also taken into account, then (according to theory) there is an ideal equilibrium point where companies have an interest in pricing their products exactly at the marginal cost of production. This is where Rifkin enters to argue the following. The production model adopted by new companies producing information technology products is such that marginal cost tends toward zero, hence the title of the book. While the marginal cost of producing a keyboard always requires raw materials and labor, producing one more copy of a word processing program requires neither, and therefore that particular program has zero marginal cost. And since companies have an interest in selling at precisely this price, an inherent contradiction arises in this model of capitalist production. In other words, they attempt to extract profits at the same time that their economic logic compels them to sell their products at zero price. For Rifkin, the way out of this contradiction will come in about half a century from now (so he calculates), when this production model will have fully dominated, its internal logic will have displaced profit-seeking companies, and goods will be exchanged freely within a fully networked world, where the primary actors will be collaborative communities, early versions of which we already see in open-source software communities.

Taking the ideal models of economic theories at face value is itself a sign of naivety, self-interest, or, more likely, a combination of both. Using pieces of critical theory (since Rifkin also refers to Marxist analyses regarding the automation of production) to support such positions, and not only failing to raise objections, but even being perceived more or less as a guru, is certainly a sign of intellectual decadence. And not just of Rifkin’s. One doesn’t need to be a profound expert in economic theories to realize that the above reasoning has gaps. Unfortunately for Rifkin, there is also the capitalist reality of the last forty years. According to official statistical research (from those commissioned by Rifkin’s employers), corporate profits, as a percentage of GDP, not only are not declining, but are actually on the rise, in contrast, of course, with real wages. At the same time, the companies with the largest revenues and profits are precisely those providing services in the information technology sector (let’s remember that Google has revenues larger than the GDP of various countries), and they don’t seem particularly concerned about disappearing. And while we wait for salvation from collaborative communities, perhaps it would be good to also take a look at the increasing trends of monopolistic concentration of capital among multinational corporations. The fact that, within the current year, the richest 1% of the global population is expected to hold more than 50% of global wealth should probably be interpreted as a bug in Rifkin’s theory, not as a feature, to use the language of programmers he so admires.

To get to the heart of Rifkin’s analysis, the first sleight of hand, apart from the obvious fact that it views the economy as if it actually functioned according to free market principles and that therefore companies price at marginal cost (which applies only to a small minority of them), consists essentially in referring only to one part of the productive process. Conveniently for him, to that part which concerns reproduction – copying of a product. Except that, before an information application begins to be copied, somehow the original must first be produced. And this “somehow” involves human labor. A lot of human labor… Anyone with the slightest familiarity with this field knows that very often, from the total cost of an information system that includes both software and hardware, the lion’s share goes to the software. Secondly, and once such a system is installed and begins to operate, the cost of the software by no means disappears. On the contrary, it has been calculated again and again that the largest portion of the cost over the lifetime of a software package goes toward its maintenance and not toward its initial production. In fact, the more complex and heavy the software (and many of these packages are monstrous, with millions of lines of code), the more urgent the need for maintenance becomes. Which, oddly enough, also requires human labor. Apparently, “expert” Rifkin has no idea why that sector called Software Engineering, with its architectures, standards, and ISOs, which strive to minimize errors in code writing as much as possible, has occupied such a central position here for quite some time.

His argument could perhaps be saved if we assumed that automation in production, both of material and “intangible” goods, would advance to such a degree that there would be no need for labor at all. In his earlier book, he starts precisely from the (initially correct) assessment of an increasing trend toward automation, presenting it as a universal model for the future. Automation displaces labor from more and more sectors today. The same process had occurred earlier as well, with the industrial revolutions, but each time new job sectors opened up to absorb the displaced workforce. However, according to his predictions, today’s process is so rapid that those displaced will remain permanently sidelined. And why is this phenomenon not temporary, and why won’t new sectors be created? Rifkin has the answer. Of course, due to automation. This is what is called a circular argument and begging the question! Is a universal automation of human labor possible? Certainly. Why? Because Rifkin says so…

The truth is that it has attempted to support such predictions by referring to the well-worn and now trivial empirical fact of the expansion of the services sector. Except that some more detailed analyses (and by no means radical ones, such as Castells’) have pointed out the somewhat awkward fact that service sectors are healthier and more profitable precisely when they are closely and organically integrated with the sectors of traditional, material industry. For Rifkin, these are mere details. In a few years, self-replicating machines and three-dimensional printers will have taken over the entire production. Why? Because all production can be assigned to such machines, because human labor will no longer be able to produce better or even different products, because it won’t be cheaper in the end, because operators will no longer be needed, because even mines will be operated by robots, and so many other “whys”… Because Rifkin says so…

We will not insist any further on an economic type of deconstruction of the Rifkinian post-capitalist techno-utopia. They have their limits too, and besides, others (few, to tell the truth), with better economic knowledge than us, have already attempted it—and rather convincingly. If we persist in analyzing what is called the Internet of Things, it is because we believe that its development indeed points toward specific directions toward which capitalist production might turn, some of which may even include its contradictions. And as usual, contradictions generate appropriate restructurings as a response. And those who have vested interests in a specific mode of production have the unfortunate habit and corresponding class intelligence not to engage in some ritual hara-kiri and lose those interests defenselessly, simply because the orthodoxy of economic magicians says so.

Platform Economics

Let us assume that the Internet of Things indeed constitutes an attempt at hyper-intensive automation of production. Such a thing is a plausible assumption, especially if one takes into account the fact that beyond the gadgets and mirrors for natives, a large part of the technology of interconnected micro-sensors and the analysis of the Big Data they will produce and transmit is already intended for use in industrial sectors (e.g., in the analysis of data from factories, machines and means of transport for the prevention of unwanted conditions and anomalies). In such an environment, if companies that specialize in the provision of services face a problem of declining marginal cost or generally a problem of surplus value appropriation, then what alternatives do they have? If they simply seek greater profits at the same time as they automate their production, how could they react (in case they are not run by aspiring communists who “what to do, they found themselves in this old capitalism and now they will donate their profits”)? Above we referred to the close relationship between services and industry. What they can do is to connect even more closely with industry, through the broader circuit of commodity circulation. In other words (and as Caffentzis has argued), they have the ability to maintain their profits by “forcing” – through an unspoken agreement of employers – industry and those sectors that rely on increased human labor into more intense surplus value appropriation and into a transfer of profits from one level to another.

Beyond this vertical integration, however, there is also the possibility of a horizontal type of connection. As a specialist informs us, the future for the business model of such companies in the age of the Internet of Things is so-called platform economics:

“If you produce value, then you are a typical product production company. However, there are also new systems in which value is produced outside the company, and this is a platform business. From its app store, Apple takes a 30% share from the innovations of other people.7 I define the platform as a published standard that allows others to connect with it, along with a governance model that sets the rules regarding who gets what.”

Van Alstyne, The Economics of the Internet of Things, MIT Technology Review.

In this case, the challenge is for one to manage to bring as many activities as possible (productive, consumer, social…) under their platform and unify them into a single system. Once this is achieved, imposing fees for movement within it becomes a simple matter. At the same time, the risk of developing new products decreases as it is transferred and distributed among aspiring producers who seek to connect to the platform. Someone malicious could call such practices hustling and black labor.8 In economic and technical terms, it might also be called labor cost compression. In the world of the Internet of Things, it is called platform economics. However, a subtle and wholly political issue arises here. As the specialist himself informs us:

“In many cases, such governance models have not yet been established. For example, population density can be determined through the distribution of mobile phones. This data belongs to a telecommunications company. In what way can you provide it with incentives to share it? All these sensors collect data, but how do you share the value?”

As even the most naive person can understand, whoever controls such data (and also their sharing protocols, we would add) within such a dense network, will automatically possess an unprecedented level of control over vast segments not only of production, but of social life itself. And if we leave aside fantasies about their democratic distribution, then economic competition between companies and even entire geopolitical blocs may not be conducted with the expected finesse and grace.

There is another side to this whole story that we have left aside until now. The universal quantification promised by the Internet of Things, from biological functions to social relationships, to the extent that it will not occur within a disorderly society, as various people imagine, but rather within the underground of capitalist reality, can only mean money. All these data will be produced by some and sold to others—and this is already happening, moreover. All these data will be translated into commodities. In other, more heroic eras of capitalism, this process was called opening new markets and extending the market into new territories. The territories may no longer be geographically defined and certainly do not involve material goods. The new territories consist of bodies and social relationships (once, some spoke of the social factory. Who could have known?). And something else too. The future itself. The fervent desire in many related research efforts is to use such dense networks and the massive data they will produce for predicting future states and exploiting them in order to detect profitable opportunities early and avoid or reduce losses. Every enterprise, of course, makes estimates about the future. However, here there is a subtle difference. The data themselves (along with the estimates, perhaps) will be the commodity. Data whose content will refer also to (future) human behaviors and social relationships.9

Communism? Wait for it in your (smart) ear

The historical evolution of capitalist technology has witnessed numerous episodes where new technological “miracles” gave rise to rhetoric about transitioning to utopian societies that transcend toil and labor. There is no need to elaborate at length on whether such hopes, recurring over time, ever materialized. The discourse surrounding the Internet of Things, however, repeats similar patterns of thought, and it seems that short historical memory serves its purpose well. The purpose of this article was not merely to deconstruct the relevant arguments, something which proves rather easy. It is also the task of critique to discern behind the noise actual tendencies, predispositions, and possible directions. If there is something we can faintly discern at this historical moment, it is nothing other than the (old, very old) insatiable logic of extending commodity practice into aspects of society that had remained relatively shielded or, at any rate, only indirectly integrated as parts of the commodity circuit. Ubiquitous computability… could also mean ubiquitous commodification.

We will close with a comment on political anthropology, if we may use the term. The dream of rationalists everywhere, from Leibniz to the logical positivists, was to construct a language with a mathematical structure that would allow the reduction of all thorny social and political issues to unambiguously solvable technical puzzles. What they refused to understand was that ethics (or, for those who might feel uncomfortable with this term, value judgments in general), together with the responsibility that it automatically entails, always constitutes the context of every logic, the framework that shapes the directions it will take. With the Internet of Things, their dream seems to be taking flesh and bone. The universal quantification and algorithmic management of all these quantities for regulating even everyday activities allows that seemingly relieving stance of being absolved from the burden of responsibility (since the numbers say so…). Instead of further commentary, we will cite an example from the not-so-distant past. When Nazi concentration camps began to devour Jews, Roma, communists, and other undesirables by the thousands, the first method of extermination they employed was the classical and time-tested one of execution by firing squad. As the rate of extermination gradually rose to industrial scales, officers faced a problem. The soldier-executioners began to feel somewhat uncomfortable, due to a slight prick of their moral conscience. The solution they found was simple. The camp was transformed into a factory, and the method was automated in such a way as to allow the mass and uniform movement of prisoners, without direct contact with soldiers, who were reduced in number and merely called upon to open doors, close doors, and push buttons. Those buttons that released gas and moved the ovens forward.

Separatrix

- The story is of course fictional, however many of the individual details and applications are already a reality. ↩︎

- The translation of the term into Greek is not so easy. Paraphrastically, and somewhat awkwardly, the truth is, we could translate it as “ubiquitous computability”. ↩︎

- If nothing else, it is worth reading this report for the chapter titled 2020: A Day in the Life, if one wants to have fun with stories like the one with which we started the article. ↩︎

- Horizon 2020 ↩︎

- Rifkin, a well-known economist, has served, among others, as an advisor to several companies and governments. In 1995 he published a book with the emphatic title The End of Work, in which he argued that new automation and information technologies would result in the disappearance of work. It is expected, of course, that the aforementioned intellectual belongs to the most ardent supporters of the Internet of Things. See also high tech intensity, Sarajevo, Issue 91, January 2015. ↩︎

- In some of his arguments, but also in Negri, a convincing answer can be found in the article by George Caffentzis, The End of Work or the Renaissance of Slavery? A Critique of Rifkin and Negri. ↩︎

- Various programmers can upload applications they have created themselves in their “free” time and price them as they see fit. For each download of the application, Apple receives a percentage, simply because it hosts the application in its app store. ↩︎

- And here, in our opinion, a large part of the activity of free software communities falls into place. But this is another discussion that we might open at some point in the future. ↩︎

- There is a very familiar example of economic practice that deals extensively with betting on future production and is called the stock exchange. Therefore, when the actual production, upon which bets have been placed, happens to deviate significantly from the expected, this is called a collapse, and some people, on the other side of the planet, may find themselves starving. In the Internet of Things, when behaviors do not align with predictions, what form will collapses take? And conversely, what means of coercion should perhaps be mobilized to avoid deviations? To avoid misunderstandings, we do not in any case embrace the once-popular theories of casino-capitalism. On the contrary, we support, if it has not already become clear, that we are talking about organic outcomes of capitalism. ↩︎