Does language have socio-political dimensions? Even when we are dealing with technical terms of a science? From the perspective of contemporary linguistics of structuralist inspiration, such questions seem non-sensical. What matters is the position of a sign and its relations with other signs within a network. Everything else appears to be the result of conventions, more or less arbitrary. An example from the history and language of computers may perhaps reveal certain cracks in the received wisdom of linguistics. We are used today to speaking of a computer’s memory, without wondering what meanings such a technical term—“memory of a computer”—might conceal. Do computers really have memory? Since when? And what relation does this memory have to human memory?

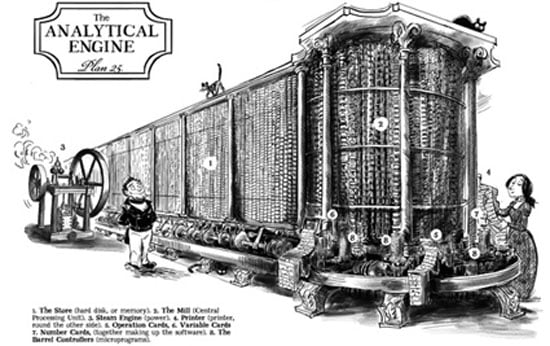

When Babbage, in the first half of the 19th century (a contemporary of Marx), was designing his analytical engine, he introduced an architectural innovation. He separated the part of the machine that would be responsible for the calculations (additions, multiplications, etc.) from the part that would be responsible for storing the initial numbers and the results. However, he never used the term “memory”. He named the computing part the “mill” and the storage part simply “store”. Why did he choose these terms? He borrowed them directly from a prevalent work model of his time, and indeed from the most advanced in terms of industrial development. From the textile industry, where piles of yarn were initially placed in a store to later go through a processing stage and return to the store as finished products. The economies of scale (for the standards of the time) were his model for designing and naming the parts of his own machine. And it is a matter of historical record that Babbage had a strong interest in economics, so much so that he even wrote a popular book on economic theory (Economy of Manufactures).

The term storage remained in use for almost a century, even in the early designs of modern electronic computers during World War II. When von Neumann, toward the end of the war, proposed his own architecture for modern computers (which closely resembled Babbage’s), he also introduced a small terminological change that eventually prevailed: he renamed the storage as memory. Von Neumann’s motivation was not economic. The source of his inspiration lay in his engagement with mathematical logic and with the organizational principles of the brain. It was the time when scientists began to explore the idea that the brain is a symbol-processing machine, and when the press welcomed the new machines by calling them “giant super-brains.” A little later, out of this convergence of neuroscience and informatics, artificial intelligence would be born.

Through this journey, the very concept of a computer’s storage was re-signified, and conversely, so was the concept of cerebral (human) memory: as a repository of data ready for processing. With measurable size, scarcity and value—exchange value.