It is to be expected that in periods of major social changes, most of those experiencing them do not understand either their full meaning or their consequences. A critical real-time examination of such changes — that is, while they are actually happening — requires persistence, a certain degree of detachment, and a solid set of theoretical tools and methods that allow analysis beyond the obvious. Obvious things and "self-evident truths" which are often misleading.

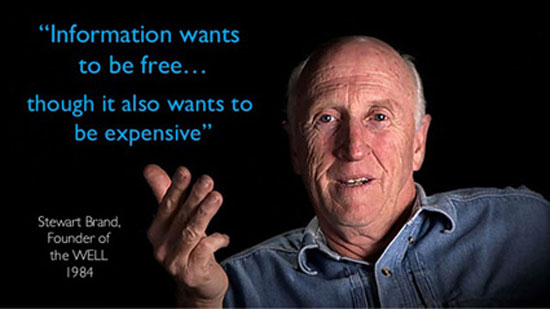

We are already living through such a period, broadly speaking, for the past 20 years. These two decades are not uniform in terms of the intensity and scope of the changes. Moreover, since these changes often originate or culminate in technological issues, understanding them is split in two. On one hand, specialists (and there are many, across numerous fields) perceive these developments as a linear, cumulative process of technical achievements that simply represent the apotheosis of human ingenuity. On the other hand, the vast majority — the "users" — perceive the "applications" they encounter through criteria of ease, effectiveness, and utility, accompanied by a corresponding sense of awe: a mixture of admiration and submission.

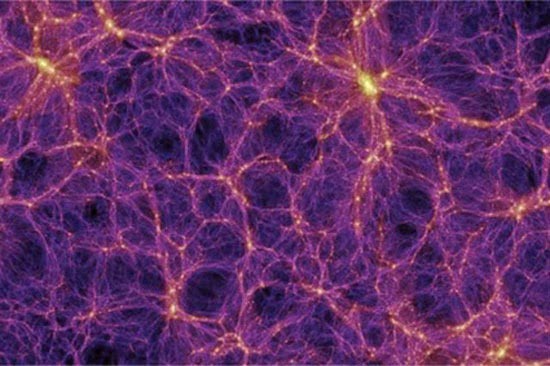

However, the real changes — those that have already shaped and will further define in the near future major shifts in social relations, attitudes, and views on almost everything — these changes are largely "invisible." Not because anyone is hiding them — not at all. But because detecting them requires, on one hand, detachment from specialists' ideologies, and on the other, detachment from the superficiality of "utility."

(For example, the private automobile was once considered, over a century ago, a "technological marvel" and an "attractive and useful thing." Just like electricity. Just like the telephone. Yet each of these — and all of them together — radically changed the world, relationships, perceptions, and everyday life.)

Mobile telephony is the most familiar and widespread transformer of social relations within less than a generation. It started as a portable, albeit bulky, device resembling military and police radios, and is now on the verge of becoming the universal remote control of life. While this machine/device has changed at least five or six times in less than 20 years, those who use it deny that any serious change has occurred in their lives. Or, if they acknowledge some changes, they cite only the "positive" ones. The fact that it has become absolutely indispensable (as a machine) in daily life is not considered a "serious change." Which says a lot. Among other things, it means that the criterion for what constitutes a "serious change" in life has been lost.

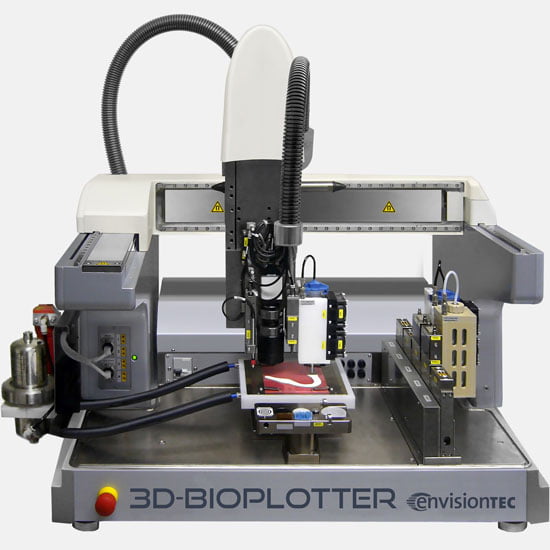

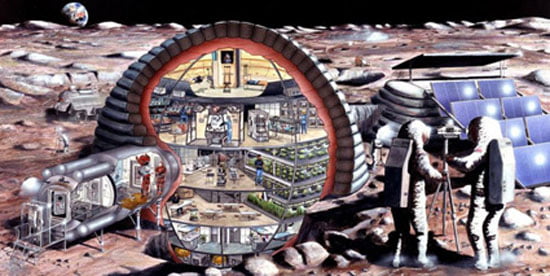

Something similar is happening with the Internet of Things. In provincial Greek society, it seems like something that will come in the future. But it is already here! Every modern vehicle, whether a car or a motorcycle, is already a small "Internet of Things." Various sensors are located at different points in the machines, "communicating" with each other and with the "central computer," algorithms process the data, and through a small screen, indications of the machine's and vehicle's proper or improper functioning are displayed. Moreover, as automation rapidly advances and fully autonomous vehicles are already being tested, once certain (social) fears are overcome, travel will become "boarding into small moving Internets of Things" — just as air travel is when the autopilot "works."

These appear as pleasant developments. From some perspectives, they are, to the extent that they facilitate... However, they are not miracles. They are developments within capitalism! And this is not a sociological or political obsession. It is an indication of the less "visible" fact that whatever reaches the "general public" as a convenient marvel or convenient mechanical service is nothing more than the tip, the extreme edge of a much broader, wider, and deeper process that is already restructuring our lives uncontrollably. It is the "free gift" of generalized mechanization. Where scattered benefits for consumers are insignificant compared to profitability, capitalist accumulation, control, and the power of a small number of corporations and state mechanisms.

Social relations (under capitalist control) create technological marvels; and these, in turn, change social relations. This iron dialectic is "invisible" and intentionally, deliberately remains so: exactly where consumers/users of whatever technological marvels "believe" they always have control over their lives, that is precisely where they have lost it! For the benefit, of course, of the owners of the world.

Critical analysis is obligated to expose this dialectic, even if it faces "deaf" and "blind" — that is, faithful — audiences; even if it seems "eccentric." In fact: modern critical analysis faces, as its adversary, the very "object" it studies, in its most socialized forms: the mechanization of thinking itself! Magical, irrational thinking has not only religious origins and support; it also has a "technological backdrop," in the sense of fetishism, a psycho-emotional stance toward techno-scientific developments, and ignorance mixed with awe...

This is a new, strange, and difficult opponent, one we must confront, with no historical precedent to guide us...

Z.S.