Algorithmic Governance - The term is new. Apart from specialists, the word "algorithm" remains mysterious. The formal definition, however, helps clarify (from the Greek Wikipedia):

"An algorithm is defined as a finite sequence of actions, strictly defined and executable within a finite amount of time, aiming at solving a problem. Put more simply, an algorithm is a sequence of instructions that have a clear beginning and end, are unambiguous, and aim to solve a specific problem.

The word 'algorithm' originates from a treatise by the Persian mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, which contained systematic and standardized solutions to algebraic problems and is perhaps the first complete treatise on algebra. Thus, the word 'algorithm' gradually became established over the following thousand years with the meaning of 'a systematic process of numerical operations'...

No matter how complex or 'mysterious' an algorithm may seem, regardless of any anthropomorphic characteristics attributed to it (such as 'intelligence', 'sensitivity', etc.), it remains exactly that: an arrangement—a breakdown and reassembly—of a process into 'steps'. When the process is completed in this way, a specific result must emerge.

Although the early pioneers of this kind of analysis, decomposition, and step-by-step structuring (such as Turing) had clearly emphasized this, in the evolution of 'developments' in computing and cybernetics, it seems to have been forgotten: the algorithm (and algorithmization, as a process) concerns what is called 'intellectual labor'—anything involving thought. In other words, the algorithm (algorithmization) is the mathematical and mechanical simulation of thinking; just as the bicycle (or the car) is the mechanical simulation of terrestrial locomotion.

Therefore, if someone is able to: a) analyze not only the physical actions but also the commands/thoughts involved in a practical task—say, moving a glass across a table; b) convert those thought steps into a binary system of 'yes or no'; c) convert these 'yes or no' decisions into the presence or absence of electric current through appropriately configured circuits; and d) direct this flow of electric current either to a screen or to some form of mechanical motion, then they have brought about the 3rd and 4th industrial revolutions!

We're not oversimplifying! Although the technical dimension is impressive, the real questions (those concerning everyone's everyday life) are not related to individual technical knowledge, but rather to the awareness of how extensive this 'electromechanical mediation' (guided by algorithms) already is—and can become—within social relationships, and what its consequences are. Analogously, these would be questions of the same order as those concerning the electromechanical mediation of movement: from the consequences of the widespread adoption of sedentary mobility to the effects of the generalized use of the internal combustion engine, from economic, social, labor, environmental, and any other perspective. Just as one does not need to be an automotive technician to engage with answers to those questions, one does not need to be a computer or programming technician to grapple with the characteristics and consequences of the 'engineering of everything!'

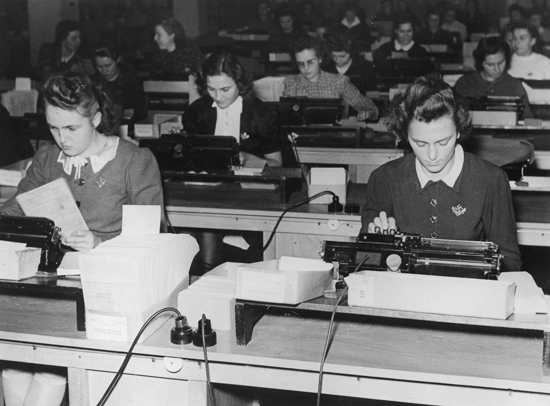

There is some scattered international literature on 'Digital Taylorism'. The strategic shortcoming of the texts we have encountered so far is that they limit themselves to the organization of labor—to digital management in various work sectors.

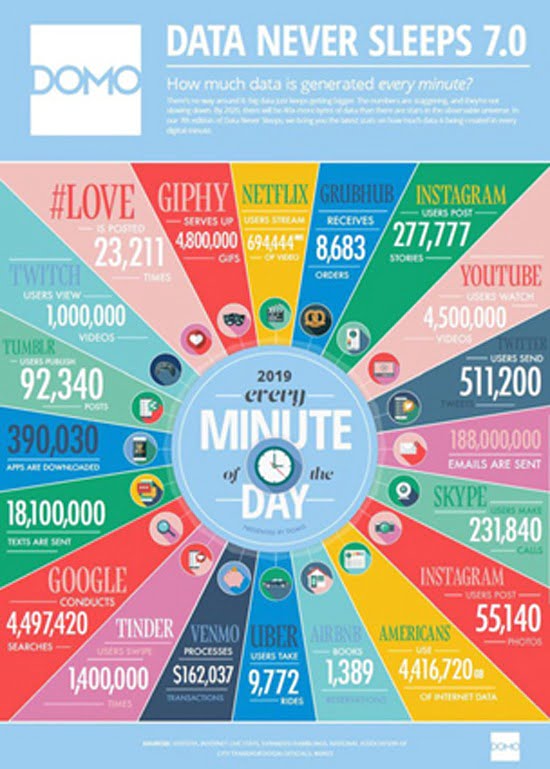

But what is literally revolutionary (from the perspective of capitalism) is not only the digital reorganization of labor. It lies in the fact that, through the very same method and process (algorithmization), the entire fabric of social relations is being reorganized... And that this reorganization has already advanced significantly, being enthusiastically embraced!

The establishment of (let’s call it) 'Analog Taylorism' first in American factories at the end of the 19th century met with worker resistance, skepticism, and employer reservations... It took more than four decades for industrial Taylorism to become the norm. In contrast, regarding its digital universality, enormous strides in social acceptance have been made in a much shorter time—and even greater ones lie ahead.

It seems as if contemporary societies have been 'enchanted' by the 'convenience' and 'immediacy' of this explosively evolving technological (but also political, social, legal, aesthetic, and psycho-emotional) restructuring. These societies appear to have been blinded (and numbed) by it...

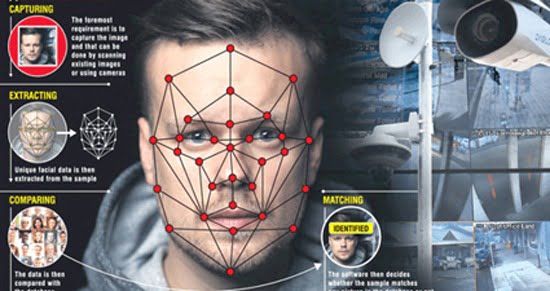

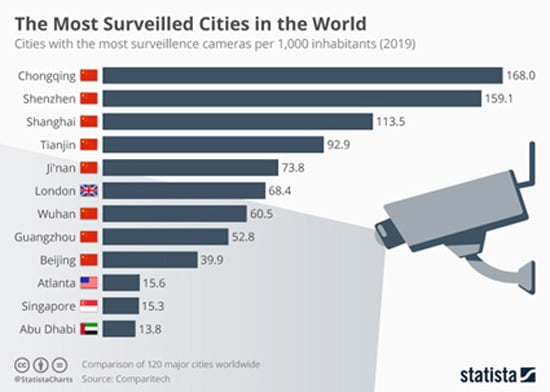

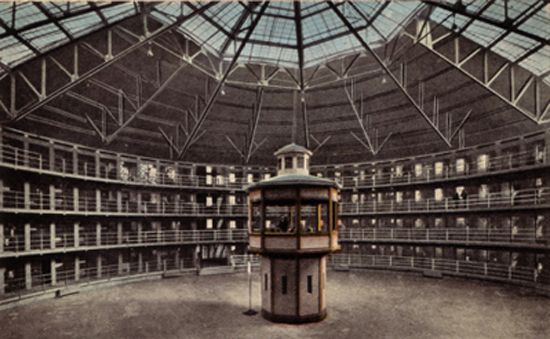

surveillance and discipline in the 4th industrial revolution

Foucault in cyberspace: surveillance, sovereignty and embedded censorship

big data: monitoring and shaping behaviors in the 4th industrial revolution

neurobehavioral signals: “health” instead of “defense”

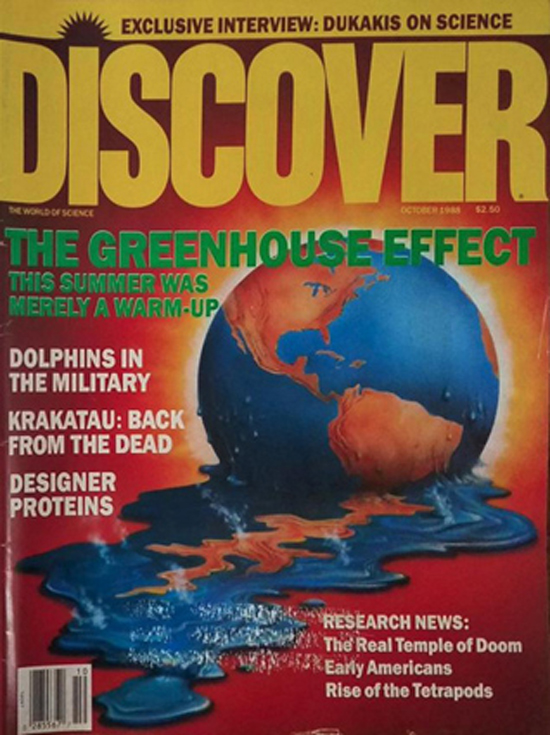

the ideological management of climate change

the racist origins of the American high-tech industry

the castration of flies