O Hacker, where art thou?

Speaking of hacking, we are referring to what has become established as black hat hacking. For those who may not know, within the “community” of hackers (which is neither one nor a community), there have been epic battles regarding who is entitled to call themselves a hacker and who is not, and the search for the definition of the “real” hacker brings something akin to the search for the Holy Grail. According to the established wisdom that is passed down to us:

hacking had a more general meaning and basically meant being inventive and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. Hacking wasn’t limited to just improving an operating system. You could hack any medium, it didn’t necessarily have to be computers. Hacking as a general concept is a stance towards life. What’s fun for you? If discovering playful smart ways that were considered impossible before is fun, then you’re a hacker. Around 1981, when journalists learned about hackers, they completely misunderstood them and thought hacking meant breaking into system security. That’s not true. First of all, there are many ways to hack that have nothing to do with security, and secondly, breaking into system security isn’t necessarily hacking. It’s only hacking if you do it in a playfully clever way.

This is what the prominent Richard Stallman has to say about how the “real” hacker is defined1. For hacking purists, therefore, those who breach security systems are not necessarily hackers. Especially for them, the rather derogatory term cracker is reserved, or, when the term hacker is still used, it takes on certain prefixes. White hat hackers for the smart kids who breach security systems in a consensual way, as part of their job and with the ultimate goal of enhancing the system’s protection. Grey hat hackers for the free-range scouts who discover security gaps on their own initiative, outside of any contract, but rush to report them to the system administrators and sometimes fix them for a fee. And finally, the devilish black hat hackers, who infiltrate systems exploiting security gaps known only to them, with the purpose of causing damage or gaining benefits, whether financial or simply exploitable information. Quite a convenient (for many…) classification scheme. We could bypass all this hacker filioque by going straight to the subject of the article. However, we will pause for a moment, for reasons whose usefulness we hope will become apparent in the following.

In his attempt to emphasize the playful nature of hacking (as opposed to the obviously malicious version), Stallman’s above definition suffers in several points, one of which is obvious even with a simple reading, without needing to resort to historical texts. And the problem is that it is such an expansive interpretation of hacking that it makes the concept encompass everything and ultimately nothing. If hacking means “I play around in a playfully clever way,” then Escher was a hacker-artist, Joyce a hacker-literateur, Antetokounmpo a hacker-athlete, “the one who sets it up at the seaside” a hacker-driver, and the list goes on endlessly. Not to mention the ultimate hacker-joker of all time, the sublime Gargantua.

In any case, if there is one point of some general consensus, it is that hacking involves, in one way or another, the technical medium of the computer. A second and more important such point concerns its time and place of birth. The time is the 1960s and the place is MIT. This particular university, through the famous Radiation Laboratory, had already played a significant role in developing advanced military systems since World War II, and by the end of the 1950s was granted, in the form of a donation, a computer that had previously “served” in the army. Around this computer, as well as subsequent ones provided by the company DEC, the first groups of programmers gathered, distinguished by a unique, “libertarian” culture, who would gradually self-identify as hackers.

A first observation here. During that early heroic era of hacking, the distinction made (along with the resulting hostility) was not between ethical and malicious programmers, but between programmer-hackers and planners. The latter somehow represented the traditional way of scientific thinking, the one that required the careful formulation of theories and equations as a preliminary step to solving any problem. Hackers, on the other hand, with the power provided by the computer, had a more direct approach. We write, test, and rewrite code, without heavy theories behind it, until we find the solution. As anarchic as this approach may seem, it often worked, and effectively at that, to the dismay and irritation of theorists. The distinctive culture of those “libertarian” programmers was later codified in the so-called Hacker Ethic2 as summarized in the following hexalog3:

– Full and unlimited access to computers, as well as to anything that can teach you something about how the world works. Hands-on experience4 always takes precedence.

– Information should be free.

– Suspicion towards Authority and promotion of Decentralization.

– The criterion by which hackers should be judged is their hacking abilities, not irrelevant factors such as degrees, age, race, or position in a hierarchy.

– You can create art and beauty with a computer.

– Computers can improve your life for the better.

As can be seen from the above moral code, no distinction was made between good and malicious hackers. And the reason was not that there were no individuals trying to exploit security gaps for personal gain. The so-called phreakers, who managed to make free long-distance calls by mimicking through various means (even with their voice) the frequencies used by telephone networks, were among the most well-known cases. Things began to change from the ’80s onwards, when the game and the interests involved in the spread of personal computers thickened, and the media found the opportunity to demonize hackers.

Second observation. Stallman is indeed right when he talks about journalists who misunderstood hackers, but he tells only half the story, the one that suits him. Because before journalists “misunderstood” hackers, some of his colleagues had already taken care to “explain” them and present them as mythical figures, roughly as heroes of the information revolution.

“Hackers are not just some technicians. They are a new, moving elite, with their own equipment, their own language, character and humor, their own myths. These wonderful people with their flying machines map the frontiers of technology, a strangely weightless and gentle technology. A country of outlaws where the rules are not like judicial decisions or bureaucratic routine, but a resonant call for exploring the limits of the possible.”

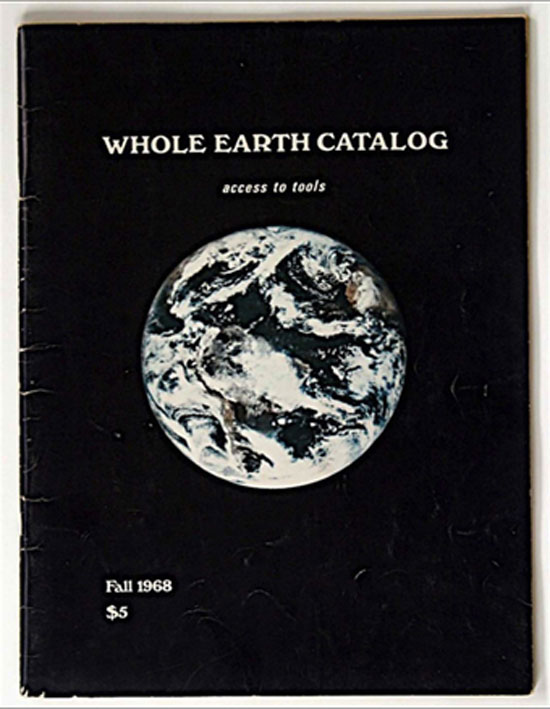

This was written in 1972 in Rolling Stone magazine by Stewart Brand. The name here carries weight. Brand became primarily known as the publisher of the famous Whole Earth Catalog, a sort of magazine that for a brief period at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 70s served as something of a bible for a large part of the American counterculture movement. And more specifically, for that segment which promoted the logic of “returning to nature,” communal living, and often – frequently – the adoption of semi-religious systems, mostly borrowed from exotic Eastern traditions.

There are several points worth noting from this brief stop at the origins of hacking, particularly the apparent contradictions that ran through the rhetoric and practice of the time. On one hand, the direct involvement of the military in the development of computer science, and on the other, the “libertarian” culture of programmers. From here, the return to nature and New Age spirituality, and from there, at the same time, the celebration of gentle, new technology. We will encounter these elements further on. For now, what we want to emphasize is the following, which is self-evident—though evidently not so for defenders of ethical hacking. How something is defined has little to do with an abstract, moralistic, and transhistorical—transsocial—definition, if by that one means something detached from context. It is precisely the social dynamics that determine where the cue ball of definition will land. And while it may be legitimate to claim the right to define and appropriate a concept of critical importance, an equally distorting effect can arise from an obsessive adherence to definitions based on ahistorical morality, or otherwise on moralizing discourse. This distorting effect is often referred to as ideology…

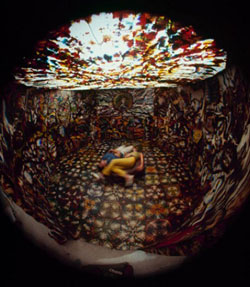

Many communities of the 1960s attempted to follow his construction ideas.

Hacking in the 21st century

Based on what we have said so far, it seems that hacking has gone through two phases. Initially, a phase of academic innocence and hobbyist experimentation during the 1960s and 1970s, and then, in the 1980s, when personal computers began to spread, a phase of demonization. From loosely organized groups of programmers sharing computing resources to the figure of the teenage lone cowboy hacker in front of his own computer in some basement. These stereotypes (or some mixture of them) more or less continue to dominate the media, with cases such as Aaron Swartz, Anonymous, and the LulzSec group still setting the tone. Or has there perhaps been a third phase of evolution?

The well-known hacker magazine Phrack published in 2008 an article titled The Underground Myth. Note: this is not just any magazine that circulates in bulk, but one of the oldest and most respectable in the field. In this article we read the following:

Few can deny that the flourishing of the cybersecurity industry coincided precisely with the decline of hackers. The hackers of the 80s and 90s became the security professionals of the new millennium, something that was a heavy blow to the community.

The fact is that hackers, individually, decided to use their passion as a source of income.

Almost all hackers who could find a job, found one.

The culprit for this is the security industry, which exploited, cultivated, and shaped this culture for its own needs. What’s truly sad is that security companies haven’t realized they’re sitting on a goldmine and that, as a result, the goldmine is likely to collapse, dragging them down with it.

But these hackers are not going to remain that productive indefinitely. They will lose their technical advantage, move to other fields, perhaps climb the management hierarchy, and then retire. The question is: and then what? Then the new wave of young professionals will come, whose motivations will be not only passion for technology and the hacking game but also financial.

Imagining that these new office employees, with their university degrees and their indifference, will be equally capable as a real hacker, is laughable.

So the hackers grew up and found “regular” jobs. But if the underground scene dried up from free shooters at the same time that the security industry exploded, then what exactly are all these security professionals doing? Are they spending their time on Facebook, lacking threats? Not exactly. The above article continues with the other side of the coin:

“From the Sundevil operation5 to cyber-terrorism. The criminalization of hacking and hackers themselves had a catastrophic effect. Hacking was criminalized in two equally important ways: through cybercrime legislation, but also by the emergence of real criminals who used hacking as a method of deception.

A clear distinction must be made between these two. Between the fact that the entire underground scene was legally criminalized for something they had been doing for decades, and the fact that, in common perception, even among professionals, who generally should know a few things better, no distinction was made between real hackers and criminals who used hacking merely as a method of profit extraction.”

It would obviously be naive to expect that hacking, by its very nature, would remain immune to the lure of crime. How exactly, however, the dialectic of the profitable cycle that connects state, corporations and crime is structured, this time also in the digital fields, is perhaps worth examining further.

What is the turnover from illegal drug trafficking? Some estimates put it at around 1 trillion dollars. 1 trillion… To get an idea of the scale involved, it suffices to note that only 15 countries on the planet have a GDP greater than this figure. How much does cybercrime turn over? The agencies monitoring its development still find it difficult to provide accurate estimates, but the general consensus is that it operates in the same order of magnitude, with many estimating that it has now surpassed the turnover of narco-crime.

Is it possible for such amounts to pass through the hands of some isolated black sheep looking to fill their pockets? In February 2013, within a little over 10 hours, around 40 million dollars were withdrawn from ATMs around the world using stolen credit card details. If we say that the job was not done by a single person alone, we won’t surprise anyone. In New York, prosecutions were filed against eight people. Almost all of them were under 25 years of age and most likely had no particular technical knowledge regarding computers and networks (two of them were bus drivers). This group, whose leader was eventually murdered in April 2013, appears to have been just one of the lower links in a hierarchy, having the specific role of a “casher crew,” that is, a redemption team that simply receives counterfeit cards to withdraw money. And if there are such dispersed redemption teams around the world, then there must also be other groups with different roles. Such as coordination groups (such operations don’t happen within 10 hours across different countries without coordination). Or hacker groups that infiltrated bank systems to steal card data. According to experts, the groups involved in such activities have a fairly developed division of labor. Here are some of the subgroups: programmers who build the breach software, distributors who sell either the software or stolen data, technicians who maintain the hardware infrastructure, hackers who carry out the attacks, “mules” who redeem and transfer money, “cashiers” who handle money laundering, and of course the leaders who recruit, select targets, and manage profits. And if you’re not impressed yet, let us also mention that we’re not dealing here with programmers occasionally employed for quick profit. The most advanced groups employ programmers on a permanent basis for research and development of appropriate tools, and some don’t just sell tools but offer services for hire (they are paid to attack wherever the client wants).

In other words, and to avoid tiring the subject, we are talking here about geographically distributed, organized enterprises with a high division of labor. Or otherwise, simply and plainly, about organized crime. And no, it most likely does not concern “isolated incidents.” Some estimates raise the proportion of organized crime’s share of total attacks to 80%. Some more conservative estimates speak of 20% coming from criminal organizations, with 70% attributed to smaller and more loosely organized groups (because even here, as in traditional organized crime, there is a gradation regarding the complexity of the organizational level)6. And what about hacker groups, like Anonymous, that cause such a stir? Those represent a small, humble, yet “heroic” 1%…

But where is this useless state at last?

Here it is, don’t worry (is Mars missing from Lent?). And it’s not useless at all. In 1985, at a state-insurance-broker-batshit crazy conference in America, when a university academic who deals with terrorism dared to hint that states can also practice terrorism, the audience, as expected, treated him somewhat hostilely. However, someone in the audience, a member of some intelligence service, stood up to defend him. The academic recognized in his defender an old professor of his from the university. When he later asked him why he left the university to become an agent, the answer he received was the following7:

“You know how much I love computers, algorithms, data. Who do you think has the largest computers, the greatest computing power, and the best access to data—and lets me play with such toys every day?”

If estimates regarding the scale of organized cybercrime are difficult, those concerning the capabilities of state-sponsored cyber hacking are even more precarious. However, from the little that has leaked out, at least some safe conclusions can be drawn. First, regarding the emphasis placed on this field, states (i.e., armies and their intelligence services) have systematically invested, for at least a decade, in developing cybersecurity tools. The American state, since 2003 when it officially began addressing the formulation of a cybersecurity strategy, has been increasing its annual investments in such directions, now reaching over $3 billion invested in such technologies (there must also be secret budgets, we assume). The friendly British state is estimated to spend a modest half billion (in pounds, of course). Second conclusion: state-sponsored cyber security tools are not intended for defensive and protective purposes. They are built with inherently offensive purposes, whether for espionage or for the physical destruction and disruption of electronic infrastructures and industrial control systems (so-called SCADA: supervisory control and data acquisition).

…My sense is that cybersecurity tools are increasingly leaning towards offense. Chris Inglis, until recently deputy director of the NSA, made the following observation: if we imagine cyberspace as a football match, then after just 20 minutes of play, the score would be 462-456, in other words, full attack. I interpret this comment of his as confirmation, from the highest levels, not only of the dual nature of cybersecurity, but also of the fact that cyber-attack is a field where only states can truly play ball and produce innovations.

Via the mouth of Dan Geer, all this in 2014, at the Black Hat conference (one of the largest cybersecurity conferences), in a speech with the emphatic title Cybersecurity as Realpolitik. Who is this guy? One of the big shots of the venture capital company In-Q-Tel, whose purpose is to fund exclusively technologies for use by the CIA. Anyway, unrelated, you don’t call him that…

Let’s say it without beating around the bush. At this moment, the most aggressive hacker, with the best funding and the most technical resources, is none other than states themselves. The example of the Stuxnet virus (and its variants, such as Flame and Duqu) is indicative in this regard. Targeting Iranian nuclear facilities in the city of Natanz, the virus could suddenly alter the rotation frequency of uranium centrifugation systems, ultimately resulting in the destruction of many of them. When it was discovered in 2010, due to a coding error that allowed it to escape its initial targets, researchers who studied it were left… speechless. The complexity of its construction (which still hasn’t been fully understood), its stealth capabilities, as well as the (non-publicly accessible) information required for it to locate and control SIEMENS industrial centrifugation systems, revealed at a technical level what was anyway obvious both politically and technically: it was a state-sponsored project. And most likely of American-Israeli origin.

The story of Stuxnet, however, has another aspect that usually goes unnoticed. Although it has finally (almost) been confirmed that its source was American, the initial official statements not only denied any involvement of the U.S.A., but promoted cyber-hysteria, with the American Department of Homeland Security declaring that:

…we need to increase our response speed because we are now seeing attack methods that are very sophisticated and cutting-edge. Once control systems become the target, then we are talking about a real loss of control, which is a major source of concern for us.

http://www.computerworld.com/article/2508103/government-it/dhs-chief–what-we-learned-from-stuxnet.html

It might have been a simple maneuver in this particular case. Nevertheless, the fact remains that increasingly more talk is being heard, even from official sources, about the coming era of cyber warfare and the need to take measures. Even though at the same time, more balanced analyses insist that cyber warfare tools neither have the ability to cause large-scale destruction nor to replace real war8. Now we might be extremely suspicious, but there is also something else we have identified regarding the relationship between state and organized cybercrime9. There are quite a few experts (including Geer) who insist that a solution to the problem of protection against cyber attacks is for governments to directly engage in purchasing any discovered digital vulnerabilities. Such a black market already exists, and a vulnerability can be priced at several tens of thousands of dollars, with the price increasing the more unknown it is (and therefore no corrective update has been released yet). It is certain that cybersecurity companies are already involved in such purchases, while there are also “reports” of government agencies doing the same. The justification behind such a proposal is, of course, that this approach is more effective in the long term for the timely discovery of vulnerabilities in electronic systems. However, since our trust in the good intentions of government agencies is not very high (when you have so many secret vulnerabilities in your hands, it’s a bit foolish to patch them, and the temptation to keep them for leverage is great), we say, perhaps, (perhaps?) something like the nationalization of cybercrime lies behind it. Maybe… Maybe something like a strategy of cyber escalation.

Instead of a funeral

How was such a development possible? How did hacking, from a discourse of absolute freedom, pass into the hands of crime and the state? The Phrack article we mentioned above closes its epitaph with words like these:

The underground hacker scene has gone through a systematic decomposition, falling victim to circumstances. There was no inherent reason for this, nor any conspiracy. And there was no winner. A conquered people, but without a conqueror, without an enemy to fight. No chance of uprising. Conquered due to circumstances, perhaps fatefully.

We have reasons to doubt that things are indeed the way they claim. Technological determinism, such as the one embraced by puritanical “true” hackers, when called upon to take an evaluative – political stance (as inevitably happens), then theoretically speaking, has two paths. In its extreme version, if it wants to remain consistent as determinism, it simply shrugs its shoulders and says “that’s how it was meant to be.” Fatalism. However, since few have the disposition to bear such a burden, the alternative that opens up, as we have already said, is abstract moralizing, once references to broader social and political processes have been downgraded to mere banality. Morality in politics, however, has as much value as SYRIZA’s cries that it would tear up the memoranda. They may inspire momentarily, but quickly give way again to a fatalism. Bitter fatalism, this time.

We therefore support the following. Hacking, despite all the rhetoric about freedom, perhaps ultimately had closer ties with that against which it was supposedly directed. Something like this, as a general phenomenon of the intermingling of emancipatory rhetoric and contrary practice, should not be surprising in the first place, at least not to those who have assimilated the classic Marxist lesson on ideology: every rising class, to the extent that it seeks to become dominant, must present its own interest as universal and deploy an emancipatory rhetoric. We补充 with the following: the more general, abstract, and ungrounded this rhetoric, the more effective it is as ideology.

Back to hacking. The reason many find the ethos of hacking we presented in the first part attractive undoubtedly lies in the continuous invocation of the concept of freedom. “Information wants to be free,” “computers can liberate you” are among the most common slogans chanted by hackers. A closer examination, however, shows that here we are dealing with a specific notion of freedom. First, it is what is called the negative concept of freedom, freedom from—freedom from constraints that may be imposed on the individual. And this is the second pole of the conceptualization of freedom. The focus on the individual, above and beyond social commitments, on the individual who carries from their natural state a set of inalienable and indefinitely personal rights and freedoms. Third and last. When Stewart Brand (we remind you, the publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog) issued his 1984 proclamation about the freedom of information at the first hacker conference, he said the following:

Information wants to be accurate on one hand, precisely because it is so valuable. The right information at the right time can change your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free because the cost of producing it keeps getting smaller over time. And so you end up with two opposing tendencies.

Information as a value, therefore, that is subject to the laws of scarcity, demand, and supply. Information and freedom ultimately as economic magnitudes. And thus, behind the abstract declarations about freedom, a more specific conception of it emerges as “economic,” individual, and negative freedom. If this triptych doesn’t remind you of something, we’ll help you. It refers to the neoliberal definition of freedom, and indeed in a version that in many respects contradicted the classical liberalism of the 19th century and was ideotypically reflected in the Mont Pèlerin conference after World War II.

It is therefore not so strange that here, hackers find common theoretical ground with Sergey Brin of Google, the entrepreneur and hedge fund manager Peter Thiel, and the publisher of the techno-enthusiastic Wired, Kevin Kelly.

If one source of inspiration for hackers, even if unspoken and underground, without their own awareness, was economic liberalism, then a second came from the bowels of the military-scientific complex and went by the name “systems theory.” And here we do not mean generally the material production of computers as a result of applying these theories, but specifically an entire way of thinking. Systems theory was developed and applied for military purposes aiming to achieve the best possible control of weapons systems, incorporating the human factor into the whole technical-military circuit. Through concepts such as feedback and homeostasis, an unification of the technical and the human was attempted, and their subsumption under uniform rules10. For such a subsumption to be possible, however, the human too had to be conceived in mechanical terms, which is exactly what happened. Within the unified machine-human system, the analogy used for the latter was that of a servo-mechanism. The interesting thing here is that at the same time the concept of the mechanical was shifted towards a more anti-hierarchical and networked perception. If with the term system one can mean everything, whether mechanical or biological systems, and if feedback can function as a self-regulation mechanism, without the need for direct external intervention, then the step towards a more holistic perception becomes easy. It was precisely such holistic perceptions that found receptive ears in the anti-culture movements, reinterpreted through theories about a universal, global harmony. We insist on this point because what we describe is not theoretical acrobatics aimed at forcing conclusions that show selective affinities between hackers and the military-scientific complex. The affinities were more than formal. They were historical. In contrast to the currents of the so-called New Left, those parts of the anti-culture that insisted on embracing mystical-type dogmas were more fertile in responding to the calls of cybernetic theory, finding in them a kind of scientific legitimation. And the unconventional hacker figures that one encountered in the 1960s in university laboratories came precisely from such circles11.

With all the above, we do not want to imply, of course, that there was some sort of hacker-crime-state strategic alliance, nor the opposite, that hackers became victims of a conspiracy. We want to emphasize the role of ideology and how it can easily reproduce itself, in the absence of critical tools, even by those with the best of intentions. Also, to show that ideology can function in subtly sophisticated ways and at multiple levels, each with different functions. Yes, ideology can be false consciousness, but it doesn’t have to be only that. It must contain elements of truth. The creativity of a hacker in front of a computer, as well as the sense of power they might feel, is not merely illusion. At a first level, and indeed an intensely experiential one, the computer can genuinely “liberate.” But precisely for this reason, these initial levels also constitute the ideology’s frontline, which does not necessarily know, need not know, and often does not want to know exactly how the rearguard operates or toward which real directions it pushes. However, knowing what the rearguard does requires more than good intentions. In politics, good intentions often—frequently—end up creating useful fools. Who get consumed in theological-type debates about how many angels can fit in the head of a pin or who is entitled to bear the title of hacker.

Separatrix