It’s an otherwise ordinary Friday when the daily operations of public and private services around the world are suddenly disrupted. The UK’s National Health Service advises patients not to visit local hospitals unless it’s an emergency. Ambulances are in disarray. Scheduled surgeries and chemotherapy sessions are canceled. In Russia, call centers and certain sales points of one of the country’s largest telecommunications companies cease operations for several hours. In various regions of Russia, police are unable to issue driver’s licenses. At stations of the public railway company in Frankfurt, information screens display travel information overlaid with a strange message.

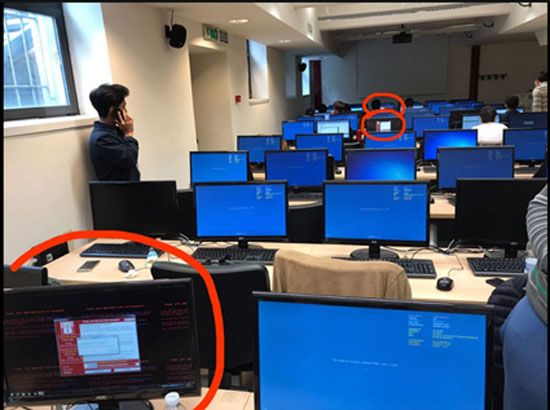

A cyber-virus is responsible for the general chaos, which manages to “infect” 200,000 machines in 150 countries within 48 hours. Public services, telecommunications and express delivery companies, factories, banks, ministries, schools, universities and home users quickly fall victim to the cyber-attack. The virus encrypts files it locates on the systems it infects and holds them “hostage,” demanding ransoms that must be paid within a specified time frame in digital currency, in order to provide the decryption key and deliver the files intact. The cybercriminals threaten that if the ransom payment deadline expires, the price will increase and subsequently the files will not be recoverable.

State public security services and cybersecurity firms have put their employees to work feverishly to deal with the virus, which has already become the top story in international and local news. At the same time, a lone researcher discovers that the virus is trying to communicate with an unregistered internet address. By registering this address, the young researcher accidentally becomes a hero, as he discovers that the address functions as an escape switch that temporarily halts the cyber threat’s attack. Soon, the story reveals the involvement of a collective of hackers who write their public texts, apparently for stylistic reasons, in deliberately broken English. The hackers have disclosed – after previously attempting to auction it online – a software vulnerability on which the spread of the cyber virus was based. According to claims by the hackers themselves, as well as official sources, they stole this vulnerability from American secret services that were using it for their own purposes.

You have surely heard this news, therefore you will know that this is not a scenario that mimics some cyberpunk novel by William Gibson, but the story of the WannaCrypt or otherwise WannaCry virus that became the top topic on social media worldwide from May 12, 2017 and for several days. The virus created a general panic in government agencies, private companies and citizens across almost the entire planet.

The reason this panic was caused is that, without warning, there was an uncontrolled disruption in some scheduled daily activities and that ultimately -due to the attack by the virus– many were forced to lose their files or even pay ransoms. It is therefore a clear attack of a cyber-weapon that created serious problems in some cases for innocent citizens. The story of WannaCrypt should however remind us in a strong way, of certain things we should already know as we move around in the digital and real world.

Let’s take things in order.

WannaCrypt

Ransomware is “malicious” software that aims to demand ransom from its victims. The WannaCrypt virus is a ransomware, which we could say consists of two basic parts. One of these is an exploit – that is, a program that exploits some security gap or software vulnerability it attacks, thus gaining access to system resources or information. The second part of the virus is an encryption program that is installed on a computer system after it has been infected.

The difference of this particular ransomware from most similar programs that implement encryption, lies in the use of an exploit that concerns a vulnerability in the SMB (Server Message Block) protocol. SMB is mainly used to provide shared access to files, printers and various communication methods between computing systems that are connected to a network. Exploiting this vulnerability, the WannaCrypt virus can infect machines with open SMB ports, gaining remote access and installing the encryption program, without requiring any action from the user of the computer that receives the attack. This characteristic of WannaCrypt led to its rapid spread to Windows operating systems that have this vulnerability.

Otherwise, for a computer to become infected, its user must make some “mistake,” such as downloading an attachment from a “malicious” email or visiting a suspicious link that leads to the download of software intended to compromise the computer. Although the WannaCrypt virus has the ability to spread without requiring such a “mistake,” it is still possible for it to infect a machine this way as well, meaning it can be installed through some user action, even if the SMB protocol vulnerability does not exist.

The WannaCrypt virus also operates like a worm – we could translate it as a “computer worm” – which means that after successfully hacking a computer, it tries to spread to other vulnerable computers connected to the same local network, checking if the SMB port is open on them. This is the reason why significant damage was caused, mainly to large enterprises and organizations.

The vulnerability of the SMB protocol, which proved so useful for the rapid spread of the virus, had been known months before the appearance of WannaCrypt, as the EternalBlue exploit that was published by a group of hackers or perhaps a single hacker named the shadow brokers.

the shadow brokers

In August 2016, the previously unknown Shadow Brokers claimed they had hacked the Equation Group, a cyber-attack group allegedly linked to the NSA (the U.S. National Security Agency). The Shadow Brokers launched an auction for what they claimed were the NSA’s top cyber weapons, initially demanding one million in the digital currency Bitcoin (approximately $568 million). The auction was unsuccessful, and a few months after the failure, the Shadow Brokers attempted to sell the cyber-weaponry tools directly, one by one, on an underground website, lowering the prices: each tool ranged from 1 to 100 Bitcoins (that is, from $780 to $78,000).

Finally, in April 2017, the Shadow Brokers released a code that provides access to all the tools which, according to the most prevalent claims, were developed by the NSA, allowing anyone to view and use them without having to pay. The hackers announced that they are releasing the code to the public as a protest against President Trump, who—as they state in a text written in a completely unserious/trollish tone—has lost the support of his “movement” due to choices such as the US military strike against Syria, the downgrading of the ObamaCare health program, the removal of far-right figure Steve Bannon from the US National Security Council, and others…

In the package of leaks that were publicly released, there is also a folder containing information and evidence related to the surveillance conducted by the NSA on the SWIFT banking system. The SWIFT network (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) enables financial institutions worldwide to exchange information. Thousands of banks and organizations around the world use SWIFT daily to send payment orders involving large amounts. Based on these specific leaks, it can be concluded that the U.S. government was monitoring money transfers between banks in the Middle East and Latin America.1

Along with the above, a package of tools that exploit vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s operating systems was also released. Among these was the EternalBlue exploit that exploits the vulnerability in the SMB protocol. This is the exploit that was used as part of the WannaCrypt virus and which was responsible for its rapid spread in May 2017.

exploits for sale

A few days after the most famous WannaCrypt attack, the Shadow Brokers announced that they would implement a new model starting from June 2017, based on which they would sell corresponding tool leaks on the black market. Interested parties will be able to pay a monthly membership subscription and receive new information every month. The zero-day exploits market – that is, software vulnerabilities that are not yet known to the software manufacturers themselves at that time – is a commercial activity that can yield great profits and for which companies and even government agencies show interest. If the Shadow Brokers’ goal is really the right one – because we can’t know for sure and probably never will – after the advertisement that WannaCrypt made for their work, they can indeed hope that their new business plan will be successful this time and perhaps they will be able to establish a good position in the black market exploits.

In the blog post where they announce the new way of obtaining the information that will leak, they claim that the US intelligence services have placed spies and former their own employees in positions at major US technology companies. They also support that the intelligence services (and specifically the equation group associated with the NSA) generally pay companies not to “patch” their software vulnerabilities until they become publicly known, but this time the NSA did not act “fairly” towards Microsoft… In their own words, if you know broken English:

If theshadowbrokers is telling thepeoples theequationgroup is paying U.S technology companies NOT TO PATCH vulnerabilities until public discovery, is this being Fake News or Conspiracy Theory? Why Microsoft patching SMB vulnerabilities in secret? Microsoft is being embarrassed because theequationgroup is lying to Microsoft. TheEquationGroup is not telling Microsoft about SMB vulnerabilities, so Microsoft not preparing with quick fix patch. More important theequationgroup not paying Microsoft for holding vulnerability.

and what happens to the unsuspecting;

The NSA has not made any statement regarding claims that the tools leaked by the Shadow Brokers were developed and used on behalf of the US. However, Microsoft’s former president Brad Smith, two days after the major WannaCrypt cyber-attack, confirmed the claims in a post on Microsoft’s blog and accused the secret services of their practice of collecting software vulnerabilities without promptly informing the manufacturers. We translate some excerpts from Mr. Smith’s text:

Early Friday morning, the world experienced the latest cyber-attack carried out this year. [..] The vulnerabilities that WannaCrypt used in the attack are based on exploits stolen from the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA). The theft had been publicly reported earlier this year. A month prior, on March 15, Microsoft had issued a security update to fix the specific vulnerability and protect its customers. [..]

Ultimately, this attack provides yet another example that explains why the collection of vulnerabilities by governments is such a major problem. This is a pattern that emerged in 2017. We have seen vulnerabilities collected by the CIA appear on WikiLeaks, and now this vulnerability stolen from the NSA has affected customers around the world. Repeatedly, software vulnerabilities in the hands of governments have leaked into the public domain and caused extensive damage. An equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be if Tomahawk missiles were stolen from the U.S. military. And this latest attack represents a completely unintended and uncontrolled link between the two most serious forms of threat today in cybersecurity – nation-state actions and organized criminal activities.

Governments worldwide should treat this attack as a wake-up call. They must adopt a different approach and, when it comes to cyberspace, insist on the same rules that apply to weapons in the real world. We want governments to consider the damage caused to citizens by the accumulation and use of software vulnerabilities.

https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2017/05/14/need-urgent-collective-action-keep-people-safe-online-lessons-last-weeks-cyberattack/#sm.001otkmya38eflr10mz1bm8c82ejz

And so, on a nice Friday, the chaos that prevails on the dark side of the cyber-dimension – which includes state services and exploits sold on the black market – surfaces and shows its teeth to private companies and citizens. All of them would not want to be affected and bothered by such problems. They simply want to do their job, read the news, open Facebook, share their photos. They don’t want to be asked for ransom for their files through their computer, nor to be interrupted from their activities.

However, the WannaCrypt story shows that the problem did not arise at the moment of the virus attack. All computers running Windows – before Microsoft released security updates after the disclosure of the EternalBlue exploit – were vulnerable to a “hole” in the software that was known to U.S. government agencies several years earlier. This vulnerability in Windows gave the American agency the ability to run its own code on remote computer systems. Since the WannaCrypt virus had the ability to encrypt files located on remote computers, we can easily conclude that the NSA, using this particular security gap, could at least read or even modify files located on the majority of computers running Windows. Public opinion appears to be less shocked by such a thing than by hackers demanding ransoms.

The prevailing view in European and American mainstream journalism is that government agencies should appropriately inform companies once they realize that information has leaked or been stolen regarding software “vulnerabilities” that they used for their own purposes. This perspective takes for granted the practice of government agencies using known security flaws in computer systems. It is a given that has increasingly been accepted over the past decade, as something that simply happens. Moreover, after the revelations of famous whistleblowers, such as Snowden, nothing changed in the behavior of technology users regarding the trust they place in their electronic devices and the internet. Ultimately, any official organization can monitor and control, as long as it doesn’t openly bother us. But if it involves “malicious” software, then we might become outraged.

Regarding the WannaCrypt story, we can say that ultimately the ransom operation was not particularly profitable. The profits that the virus managed to generate during its rapid spread, until May 15th, were approximately 50 thousand dollars in bitcoin. For the publicity the attack received, these profits were relatively insignificant. So much so, that it is reasonable to question whether the ultimate purpose of the cyber-attack was profit or publicity.

We do not know, nor will we ever learn, whether at some point in this story the American intelligence services lost control of the situation, or if this was a – from all sides – expected “accident” aimed at producing a major spectacle. Was it a mass test of reactions to a dramatic cyberattack, poor cooperation between American intelligence services and Microsoft, advertising the shadow brokers’ business for an opening in the exploits market, an event created to be used within the framework of foreign policy? We will probably never be certain…

Shelley Dee

- We will not elaborate further here, but you can find some additional information in the bbc article: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-39606575. ↩︎