Robots fascinate humans. Whether it is dystopian stories of cyborg warriors or growing concerns about mass unemployment, the robot is a science fiction archetype that haunts our cultural unconscious. But it is the military applications of robots that have the potential to reshape old rules of geopolitics. This article examines the robotic futures imagined and promoted by American military officials, think tanks, and defense documents. These futures reveal profound developments in robotic warfare, artificial intelligence (AI), and the accumulation of unmanned aerial vehicles. Bringing together these trajectories, this article analyzes how robots are transforming the spaces, logics, and geopolitics of the American empire. While robot futurism is now more systematically constructed by defense officials and academics, the term “empire” is rarely used as an analytical concept. Yet, given that “empire in some form has persisted throughout millennia and will likely continue into the foreseeable future,” the term significantly enriches our geopolitical and conceptual understandings of impending robotic wars.

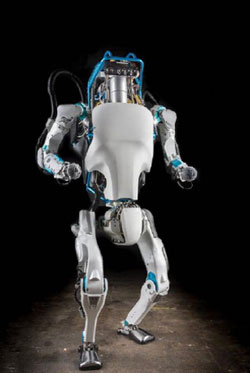

There is no unified definition of what constitutes a robot. In fact, the very name of a robot is an act of categorization that cancels out significant differences. Nevertheless, a robot is usually defined as a computer-programmable machine capable of automatic actions. This includes a range of artificial devices: flying robots, such as the iconic Predator drone; humanoid robots, such as Honda’s ASIMO or Boston Dynamics’ Atlas; smart cars; or industrial robots that work in factories around the planet. I, Robot, the classic science fiction work by Isaac Asimov in 1950, described the three laws of robotics. These were designed to protect humanity from its robotic creations. The most important was the first law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. More than 60 years later, a series of US military robots of various shapes and sizes – such as the unmanned Reaper aircraft – are now built to directly violate Asimov’s law. This may mean that “mankind’s 5000-year monopoly on conducting war has ended.”

In response to this growing robotic revolution, which is taking place both within and beyond military industrial complexes, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert O. Work warned that the American military “cannot afford to delay the time, thought, and investments required to prepare for warfare in the age of robotics.” Thus, the age of robots brings military personnel, politicians, researchers, scientists, and activists face to face with profound questions about the future of war—and even of our humanity. In all suburbs, favelas, and cities of the underbelly, we are witnessing the rise of an extensive robotic battlefield, “a shaggy and dirty Terminator Planet.”

At the heart of these forecasts lies great uncertainty, which only faintly emerges with today’s unmanned aerial warfare: how will the American military project its power in a multidimensional, multinational robotic age? To answer this question, the article turns to “empire”—a concept that has played a minimal role in the theorization of international relations. “Empire” is a significant research element for situating this forecast: it incorporates future robotic battlefields, infrastructures, and weapons into a much longer geo-history. Indeed, empire may still be “The Big Game” in global geopolitics.

Since the CIA increased the number of drone strikes with unmanned Predator aircraft under Obama’s administration, there has been a growing interest in remote warfare. […] Drone warfare continues to complicate the relationship between humans and non-humans, as well as the regimes of sovereignty and territorial control. However, today’s drone warfare is only the beginning of a robotic revolution sweeping the military: future unmanned aircraft will be smaller, autonomous, and capable of interacting in swarms. And these autonomous leaps “have the potential to radically change the way war is fought.” Robots, whether in the air, on land, or underwater, are not a distant prospect for the future of the American empire, but are already deeply embedded in its structure—and in the war landscapes it will bring about.

Consequently, this article advances a prognosis for understanding how robots will implement the possibility of a robotic American empire. “With a flexible power directed through a robotic information infrastructure,” McCoy argues, “the United States could, in principle, leverage their military power by pursuing a second American century… creating something akin to an endless American empire.” This endless empire depends on how the U.S. military turns toward a robotics-intensive form of counterterrorism. To understand this turn, we need an understanding of robots as actors transforming the materiality of increasingly non-human worlds of security and surveillance. With this argument, the article contributes to research in international relations, geopolitics, and political geography regarding the materiality of global politics and state power. Of course, the prognosis constructed in this article, like all prognoses, is necessarily contingent, fragile, and non-linear.

The rest of the article has the following structure. … The swarm war explores the impacts of creating microscopic unmanned aerial vehicles. (2) The robocosm world investigates how robots are changing the strategic military bases of the USA and producing new topological spaces of violence. And (3) the autonomous battlefield reveals how autonomous robots will produce emerging, technologically saturated spatial events of security and violence – thus bringing revolution to the space of battles. The conclusion reflects the rise of a robotic empire of the USA and its consequences for democracy.

[…]

The robotic revolution

Robots have been disrupting the social and economic spaces of human coexistence for decades. In 1961, General Motors installed the first industrial robotic arm—the Unimate—on assembly lines in New Jersey. Since then, robots have migrated from factories into the social spaces of everyday life. According to one report, there are now over 8.4 million robots worldwide, with a purchase value exceeding 15 billion dollars. And with the exponential leaps in processing power predicted by Moore’s Law, we are now on the verge of a “Cambrian” explosion of robotic life on planet Earth. This has major implications for the fields of security and violence. On land, in the air, and under water, military robots are eroding the human monopoly on violence. Today, the world is approaching a robotic revolution in military affairs that may be as significant as the introduction of gunpowder, the levée en masse [mass conscription, a term originating from the French Revolution], and the advent of nuclear weapons.

In the coming decades, American soldiers will be augmented, replaced, and struck by artificial warriors, a development that has the potential to change the fundamental concepts of defense strategy. However, the robotic revolution must be integrated into a longer trajectory of capital-intensive military operations. This liberal theory of violence aims to use technological superiority to “solve” the problem of “uncivilized” states and actors. Consequently, the U.S. military continues to promote peace through capital, security through technology. In 2014, the U.S. accounted for just over half of global arms sales, reaching an annual value of 70 billion dollars. Nevertheless, robots disrupt the architectures of capital-intensive military operations. The futurological book Future 20YY: Preparing for War in the Robotic Age sheds light on the production of robotic geopolitical futures by the American military. With Deputy Defense Secretary Robert O. Work as co-author, it insists that “American defense leaders should begin preparing… for war in the robotic age.” A similar report by the Pentagon-funded National Defense University explores how advances in synthetic life, robotics, and artificial intelligence will transform U.S. sovereignty.

At the start of the invasion of Iraq, the U.S. military had zero ground robots. By the end of 2008, there were 12,000, including the iRobot PackBot, which became an integral part of explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) missions. Aerial robots continue to disrupt spaces, issues, and the geopolitics of American conflicts. Indeed, what Kate Kindervater calls “lethal surveillance” has transformed U.S. geopolitics. The Pentagon today operates a fleet of well over 12,000 unmanned aerial vehicles [note: data is from 2013]. Medium-sized Predator and Reaper aircraft have been deployed along the periphery of “hot” battlefields in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. And on a smaller scale, the U.S. military is exploring how to equip its soldiers with pocket-sized micro-drones for aerial surveillance, which could revolutionize infantry tactics. Within the U.S., Predators and Reapers routinely fly missions for the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol along the borders with Mexico and Canada. And domestically, $55 million has been spent to transfer 1,000 military ground robots to police forces in 43 U.S. states. On July 7, 2016, the Dallas Police Department became the first to use an explosive robot to kill an armed suspect. A date of symbolic significance for robots.

How, then, can we combine these developments? Former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel presented the Defense Innovation Initiative, also known as the “third offset strategy,” on November 15, 2014. Supported by robotics, cyber warfare, autonomous systems, 3D printing, electric weapons, miniaturization, and the Internet of Things, this strategy is designed to support American technological dominance in the 21st century. The “third offset” follows previous Cold War offsets. To offset Soviet numerical advantages in the 1950s, the U.S. Army invested heavily in nuclear weapons. The second offset strategy of the 1970s was driven by stealth technology, geo-positioning (GPS), and network-centric systems. In both cases, technology was transformed into U.S. military dominance. However, unlike the Cold War, the robotics revolution today sweeps many nations (and non-state actors), not only the American and Russian military-industrial complexes. Thus, the American empire faces a robotic battlefield that is both global and unpredictable.

American Empire: towards a robot army

[…]The history of the United States is inscribed by imperialism. For Munro, “continuing to think about the United States in imperial terms allows us to see how the present is already fundamentally shaped by the economic inequality of the past, racial inequality, heteropatriarchal oppression, and a deep interplay between the spheres of the foreign and the domestic.” Correspondingly, Heumann argues that the United States has always been an imperial state rather than a national state, inheriting the legacy of European empires. Practices of racial sovereignty and expansion supported the formation of the American state and early capitalism, leaving a legacy of separation. […] The dark parade of U.S. wars and covert operations during the Cold War—especially in Latin America—solidified the idea that the United States was the guardian of Western civilization.

Despite the history of foreign interventions, the United States has consistently avoided the label of empire. This changed during the “war on terror,” as the Bush administration adopted “a new ideological commitment to empire.” Consider the infamous boast of White House advisor Karl Rove: “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.” Supporters of the American empire ranged from liberal interventionists to neoconservative hawks. According to both visions, “the U.S. state is thus regarded as an imperial state overseeing a global empire that yields benefits to both other Western states and the inhabitants of war-torn countries.” […] The question that arises is how the American empire will implement—and sustain—its dominance in an era of global robotics, technological diffusion, and powerful non-state actors. If the third offset strategy is any indication, the American empire will reconstitute itself by transitioning to a permanent, robotic proxy war.

After WWII, the practice of total war between states has diminished and proxy wars have increased. One of the most notorious examples in U.S. history was the CIA-funded Afghan mujahideen in the 1980s. More recently, the Pentagon spent billions on private military contractors in Iraq. But instead of entrusting military power to human contractors, U.S. military surrogates in the future could be replaced by robots: private military contractors without flesh, risk, or vulnerability (or healthcare costs). Advances in communication and computer technology have the potential to nullify the twentieth-century belief in “boots on the ground” as a necessity for proxy warfare. A robot army can project U.S. power without humans on the ground. And, equally important, these artificial warriors are profitable commodities. A robotic American empire thus promotes proxy war—and capitalism—to its most logical conclusion.

Autonomous futures

Autonomous systems—and artificial intelligence in general—are of central importance for the future of U.S. geopolitics. The Defense Science Board writes that “the continuing rapid shift toward autonomy in warfighting capabilities is vital if the U.S. is to maintain its military advantage.” Unlike automation, an autonomous system possesses adaptive intelligence. This allows it to be “goal-oriented in unpredictable environments and situations.” Autonomous weapons are not entirely new: since the 1980s, the U.S. Navy has installed autonomous Gatling Phalanx CIWS guns on many of its warships. Nevertheless, the modern battlefield is being transformed by “an emerging class of robotic weapons, including unmanned aerial vehicles, mobile sea mines, automated turrets, remote-controlled machine guns, as well as armed computer programs.” Several autonomous unmanned aircraft—the U.S. Navy’s MQ-8 Fire Scout, the United Kingdom’s Taranis unmanned aircraft, and the Anglo-French unmanned combat air system—promise to revolutionize air combat. […]

The American military regularly produces roadmap charts that anticipate an autonomous future: from robots that remove wounded to swarms of unmanned aircraft that crush enemies. “Autonomy in unmanned systems will be critical to future conflicts that will be fought and won with technology” (US Department of Defense, 2013). To justify the Pentagon’s pursuit of autonomy, multiple reasons are put forward: future threats will be too complex for human reactions, autonomous robots can operate if they lose wireless contact, and using pilots to oversee multiple robots is more efficient. Finally, autonomous systems can analyze massive data flows in real time “in ways that humans cannot, dealing with volume, complexity, speed and continuity.” Consequently, autonomy allows robots “to receive and execute complex decisions” (US Army, 2010). Future pilots will direct swarms of intelligent unmanned aircraft with a geographic information system (GIS) program: over the field, but not in the field. “The end result will be a revolution in the roles of humans in air warfare” (US Air Force, 2009).

This artificial intelligence model allows future unmanned aircraft to escape the limitations of existing unmanned systems. “Future [unmanned aircraft] will evolve from remotely operated robots to independent robots, capable of self-activating to perform a given task” (US Department of Defense, 2005). This self-realization allows evolution from autonomous targeting to the more controlled step of autonomous attack. However, while the US military is today a global leader in robotics, it will face in the future the unknown from other armies and non-state groups. For example, there is growing concern in the Pentagon that American soldiers are increasingly vulnerable to (swarms of) terrorist unmanned aircraft on the battlefield. Consequently, the future war with unmanned aircraft will create particularly contested airspace, fueling a robotic arms race of offensive and defensive systems.

Autonomy, however, is something more than mere artificial intelligence: it is an ontological condition. Robots, like all technologies, implement unique techno-geographies and techno-politics. Rather than being instruments of human minds, robots are geopolitical agents that disturb and reinvent the conditions of state power, installing ontological coordinates—both pre-specified and unforeseen—for future military violence. The epistemological problem of whether, or how, we go to war is inextricably linked to the material conditions of the infrastructure. Drones, for example, continue to transform the ethics of targeted killing. “Drones allow for the (de)politicization of targets by abstracting human life into a techno-political entity that can be clinically recorded as data.” Thus, although robots do not directly determine military operations, they nevertheless reconfigure the field of their possibilities. “Robots, therefore, may not only facilitate the initiation of war… they can actually change our military and political doctrines and activities.” In short, robots already possess a degree of ontological autonomy, because they reconfigure the conditions of a more-than-human warfare landscape.

New spaces of the empire I: Swarm wars

Autonomy enables the next shift in American warfare: the swarm, which has the potential to “render previous methods of warfare obsolete.” The U.S. military is at the beginning of a war ontology that shifts the projection of power from discrete platforms (such as expensive fighter jets and aircraft carriers) to amorphous and autonomous swarms. The military defines the swarm as “a group of autonomous networked drones operating collaboratively to achieve common objectives” (US Air Force, 2016). In this sense, a group of Predator unmanned aerial vehicles is the harbinger of a battle formation in miniature. The American empire will proceed further with miniaturization. The extremely popular (and hand-launched) unmanned aircraft Raven embodies the disruptive aspect of future robotic violence: smaller units and useful payloads. Indeed, researchers at Harvard have developed extremely cheap three-dimensional printed unmanned aerial vehicles that “could allow the United States to deploy billions—yes, billions—of microscopic, insect-like unmanned aerial vehicles.” Consequently, military power and vulnerability are dispersed, removing individual survival from the equation and replacing it with the resilience of the swarm. Such a quantitative change in the number and size of military robots will bring a qualitative change to the battlefield.

Swarming promotes the network-centric warfare that became popular in the 1990s. A 2000 report by the American think tank RAND places the swarm at the heart of the future military strategy of the United States. Swarming embodies a shift from the network space of the second offset strategy to the swarm space of the third offset strategy, which “will reshape the future of conflict as much as the rise of blitzkrieg changed the face of modern warfare.” Just as insect swarms are not particularly intelligent, cheap robot swarms can collectively perform complex tasks with simple algorithms. Swarms of amorphous unmanned robots are therefore ideal for achieving overwhelming dominance on a nonlinear battlefield, “creating a concentrated, relentless, and scalable attack,” using “a deliberately structured, coordinated, strategic approach to strike from all directions.” And perhaps the only way to defend against such a swarm would be with a more advanced swarm. “The result will be a paradigm shift in warfare, where mass will once again become a decisive factor on the battlefield.” Previous offset strategies substituted mass with precision weapons. The return to mass as a means of military power is, however, different from the past. Mass in the 21st century requires a molecular and flexible robotic mass: a mass that mirrors the swarms of bees, fish, ants, and birds in the natural world.

Swarming thus implements a nonlinear space-swarm: a massive atmospheric assault. Targets are secured and neutralized by intelligent unmanned aircraft that act and move faster than humans. This shifts the battle regime from the surfaces of land power and the skies of air power, to the swarm spaces of robotic power, crystallizing a volumetric and multidimensional geometry of violence. This overturns the spatial point system and the logic of human control in today’s unmanned aircraft warfare. First, swarms of unmanned aircraft will move in emergent and self-coordinating groups. Here, discrete targets and static geographies collapse: the weapon is the space-swarm itself. Second, the causal relationship between pilot and unmanned aircraft is transformed into an emergent set of rules, whereby swarms are directed by embedded artificial intelligence. Third, swarms will interact across the full spectrum of military domains (land, sea, cyber, and space), within what the military calls full-spectrum dominance.

The swarm-space could breach small corridors, crossings and urban volumes that were previously inaccessible to unmanned medium-altitude aircraft. As the U.S. military foresees, “swarms will have a level of autonomy and self-awareness that will allow them to… fly, crawl, adapt to their positions and navigate in increasingly confined spaces.” The DARPA Fast Lightweight Autonomy program is an example of an emerging category of algorithms being developed to enable robot swarms to operate in chaotic urban environments. Thus, robotic swarms—both military and non-military—could cause mass damage in cities across the global north and south and install new regimes of narrow and pervasive surveillance. Indeed, in many ways, swarms already reflect the transversal fragmentation of society, which no longer operates in bounded and linear sets, but in ephemeral, shifting groups. The modernist barriers between people, things and places dissolve into swarms, waves and foams.

New spaces of the empire II: Robocosmos

The American empire in the robotic age will continue to project technological power rather than physical vulnerability. Already, the reliance on drone warfare has transformed the geography of overseas military bases. Chalmers Johnson (2004) wrote that the twentieth century saw the American military establish a “global archipelago of bases.” During the Cold War, approximately 1700 American bases were constructed across Europe and the Pacific to “contain” communism. As a result, the American empire is “uniquely an empire of bases, not of territories, and these bases now encircle the globe in a manner that, despite age-old dreams of global dominance, would have been previously unthinkable.” The Pentagon lists 523 military bases, part of a portfolio of 562,000 facilities in 4800 locations worldwide, covering 24.7 million acres. In 2015, David Vine estimated that there were nearly 800 American bases operating in 80 different countries, at an annual cost of $165 billion. As Vine writes, “the United States most likely has more bases in foreign lands than any other people, nation, or empire in history.”

The drone has disrupted the military necessity of stationing troops abroad. By 2016, the Predator family—Predator, Reaper, and Gray Eagle—had flown over 4 million hours across 291,331 missions. Following the reduction of U.S. forces in 2014, drone strikes in Afghanistan represented 56% of weapons deployed by the U.S. Air Force in 2015, up from 5% in 2011. Across Iraq and Syria, American drones participated in over 19,600 coalition airstrikes from August 2014 to April 2017. Predator and Reaper missions in Operation “Inherent Resolve” accounted for approximately one-third of U.S. Air Force missions, while roughly one in five drone sorties deploys a missile. If these trends continue, the American empire will maintain its dominance in the age of third offset strategy not through a human-centric base system but through a cyborg Roboworld. The decline of large main operating bases following the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan has been accompanied by an increase in smaller—lily pad—American bases. Like Chabelley airfield in Djibouti, these bases are often little more than landing strips for unmanned aircraft.

There is a growing number of bases around the world that form an integral part of the U.S. military and CIA’s unmanned aircraft operations. This Roboworld has implemented a surveillance and communication network with unmanned aircraft that connects the planet via an electromagnetic rhizome. Countries that have constituted an integral part of U.S. unmanned aircraft operations include: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Germany, Italy, Iraq, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Niger, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Turkey, Uganda, and the United Arab Emirates (the Menwith Hill base of the United Kingdom and Pine Gap of Australia provide satellite intelligence). Beyond these countries, Roboworld has also monitored targets in Iran, Libya, Nigeria, and Yemen. More recently, the African continent has become a significant arena of U.S. air power. Over the past decade, the U.S. military has advanced preparations for a continental aerial surveillance network. By the end of 2015, Pentagon officials began to publicize plans for a new, integrated system of unmanned aircraft bases across all of Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East. This Roboworld is built from larger “nodes,” such as the military bases in Afghanistan, with smaller “spokes” consisting of small bases, such as those in Niger.

Roboworld aims to eliminate the tyranny of distance, shrinking the planet’s surfaces under the watchful eyes of American robots. As Paul Virilio argues, “this technological development has transported us into a sphere of plasma topology where all planetary surfaces are directly present to one another.” Within the framework of classical topographic spatiality, state boundaries coincide with physical locations, according to Max Weber’s classical definition of the state as a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a territory. Here, there is a Euclidean concept of internal and external spaces, with state power housed in measurable, mapped, and discrete areas. […] The planet’s enclosure within a technological culture has enabled all kinds of topological inversions in communication, media, geopolitics, and, of course, warfare. Thanks to radio-electronic systems, the significance of distances has been essentially nullified for centers of power and consumption. Global players live in a world without gaps.”

The topological spaces of Roboworld thus deform the supposed relationship between sovereignty and territory. Roboworld shapes and polices the surfaces of the planet. This ability is based on a militarized code-space, which absorbs distant spaces into a computational ecosystem. Consequently, within a topological spatiality, relations determine distance rather than distance determining pre-existing relations. As John Allen (2011) argues, “power relations are not so much located in space or extended across it, as composing the spaces of which they are part.” The unmanned aircraft, collapsing vast distances through robotic technique, has been the producer of a series of deadly spatiotemporal compressions. […] We can thus reinterpret Weber’s classic definition of the state not simply as the exercise of violence within a territory (topographical power), but as the control of distance between spaces (topological power). The American empire will continue to police this topological mesh. Such a robotic imperium is, however, largely one-way. American unmanned aircraft pilots can strike remote targets, but the reverse does not hold: a technological asymmetry still exists within the empire.

“By 2020,” argues Alfred McCoy (2012), “the United States will deploy a triple canopy of aerospace shield, advanced cyberwarfare, and digital surveillance to wrap the globe in a robotic web capable of blinding entire armies on the battlefield or eliminating a lone guerrilla in the field or favela.” However, the realization of such a planetary web requires an infrastructure capable of transcending the spatial topologies of human control. It requires the artificial intelligence of the robots themselves.

New spaces of the empire III: the autochthonous battlefield

War with unmanned aircraft has constructed remote power topologies that bridge human operators with distant targets. Future autonomous drones, however, will target within robotic topologies, implementing a battlefield in which humans are in the loop, but not necessarily on the loop. The management of the circuits of the war-scape will be conducted by an autonomous and adaptive system of robotic power. Future robotics, in short, challenges human intention as the agent of state violence. Consequently, we must anticipate not only the ongoing shift from geographic to topological situating, but also the transformation from remote to autogenic sites of power. The term “autogenic” comes from the Greek word meaning “self-generated” or “originating from the body.” Here, I use it to denote how robots will autonomously generate targets through the technical body rather than directly responding to human directives. This artificial intelligence erodes human intention as the sole arbiter of state power, replacing it with the machine learning of robotics. In doing so, it challenges our understandings of biopolitics.

Biopolitics, what Foucault called “state control of the biological,” is driven by the fear that anything, anyone, or anywhere can become dangerous. The U.S.-led “war on terror” mobilized this “kind of low-intensity but ever-present terror of the possible.” In Afghanistan and Iraq, the U.S. military relied heavily on calculations, biometric systems, and GIS systems. It is extremely critical that the subjects of U.S. security were identified as such through algorithmic techniques, which radically颠覆传统安全问题。数字信息成为国家权力的手段和目的。这种受技术驱动的生物政治并不针对个人本身,而是针对德勒兹曾经称之为分裂个体的新兴存在:数字信息的流动、模式和轮廓。生命不再通过虚构的身体或敌友区分来交织和保障,而是通过一种治理战争机器。例如,特征打击并不是针对已知人物,而是针对个人的敌对时空轨迹的空袭[特征打击:无人机刺杀行动,目标是符合特定行为特征的人,尽管其个人身份未知]。

As discussed in the previous section, the militarized and coded spaces of Roboworld implement a shift from Euclidean geometry, “where space is a homogeneous plane,” to the topological spaces of “pluralistic and complex spatial arrangements.” Space is not a neutral plane of existence, a container for people and things, but a disturbed field of forces: an emerging condition in which the non-human is active and energetic, rather than passive and dead. How could this affect the field of battle?

Since the 1990s, the military has used the term “battlespace” to describe a “full spectrum” environment consisting of land, air, sea, space, friendly and enemy forces, weather, the electromagnetic spectrum, and information. This concept of the battlefield supports what Derek Gregory calls everywhere war, where it is no longer “clear where the battlefield begins and ends.” However, despite these extended geographies, the space of battles maintains Cartesian distinctions between subjects and objects, leaving aside the complex and competitive interactions between human and non-human. War continues to be understood, ultimately, as a human condition. The possibility that the non-human can create and transform the battlefield is excluded.

However, the revitalization of the battlefield through autonomous robots, ubiquitous sensors, and artificial intelligence, combined with the algorithmic transformation of worlds, transforms the who, what, and how of the battlefield. Consequently, we need an ontology that frames the space of battles as a more-than-human and emerging environment, rather than as a container for military action. Caroline Croser (2007) outlines the idea of an “event-saturated” battlefield in her study of U.S. military strategy in Baghdad. To support battlefield awareness in a complex urban insurgency, U.S. commanders installed a GIS and GPS mapping program called Command Post of the Future. Crucially, the software mapped the city not as a static space of objects, but as a space saturated with events. This technological interface produced a new form of military logic: a shift from a discrete ontology of targets with coordinates and objects (e.g., buildings or battle tanks) to an event-saturated battlefield with moving bodies and bodies becoming dangerous. For Derek Gregory, “the standard object-oriented ontology of the target was increasingly replaced and bypassed by an event ontology: Baghdad was transformed into a city saturated with events.”

How, then, can we understand the process by which the hybrid ecosystems of Roboworld will autonomously execute and manage conflicts? The future battlefield, full of events, will be controlled, transformed, and destroyed by robotics. “Collaborative, autonomous systems can function as self-healing networks and self-coordinate to adapt to events as they unfold.” For centuries, technology has filtered, encoded, and monitored biological existence. In the age of robotics, this artificial horizon dissolves into millions of robots that can act autonomously: ensuring their own safety, producing their own techno-geographies, and performing their own robotic being in the world. Rather than being directed at targets deemed a priori dangerous by humans, robots will be (co)producers of state security and non-state terrorism. The age of robots is the age of deterritorialized, flexible, and intelligent machines.

We need, therefore, a mapping to understand the battlefield as robotic, self-generating, and organized based on the event. Understanding this perspective requires us to move away from the ontological baggage associated with realistic definitions of space, which usually perceive it as a Newtonian container or a Cartesian extension. Place, alternatively, is a spatial concept that highlights the ontological uniqueness and autonomy of the event, which is something more than human. Sallie Marston defines place as “an emergent property of interacting human and non-human inhabitants of it.” […] The crucial point is that a place is ontologically autonomous, “the emergent product of its own inherent self-organization.”

Consequently, the ontology of location shifts our understanding of military violence from the notion of an inert battlefield space that is overdetermined by human consciousness to the notion of an emerging battlespace, in which the robot is a co-producer of the event. The battlespace, like the battlefield, is a zone of conflict. However, the battlespace is not an a priori homogeneous space inhabited by humans and robots, but is generated internally from the composition of objects and subjects, real and artificial intelligences. Battlespaces are immanent, dynamic, self-organized spaces of events composed of bodies and representations that are not only human. They are, in other words, emergent singularities implemented through the composition of organic and inorganic forces. Autonomous robotics transforms the transcendent conditions of state violence: a roboticized American empire emerges through these battlespaces.

If human consciousness, sentiment, influence, and flesh ever directed the worldliness of the battlefield, then the battlefield is arranged by the processing of robot matter. The processing of matter is the process by which robots and humans “co-think” to realize a set of virtual possibilities and to control the local composition of worlds. […] The battlefield is not a transcendent order imposed by human will, but the possible result of a more-than-human processing of matter and machine learning.

In his analysis of warfare with unmanned aircraft, Chamayou argues that “armed violence is no longer defined within the boundaries of a delimited zone, but simply by the presence of an enemy-prey that, in a way, carries with it its own mobile zone of hostility.” Military unmanned aircraft continue to implement a “temporary autonomous killing zone.” As he adds, “depending on the contingencies of the moment, temporary deadly micro-cells could open anywhere in the world, if an individual meeting the criteria for a legitimate target has been identified there.” The battlefield is likewise an emerging micro-cube of state violence: except that, instead of being directed by the remote force of human operators, it is created by the artificial intelligence of robots.

In short, autonomous robots will implement new, non-Cartesian mappings of self-generated state violence. This moves us from the discrete battlefields of old wars, the event-filled battlefields of new wars, to the robotic battlefields of swarm wars, and these future conflicts will be composed of sites of robotic violence. This will implement an American empire that extends beyond territories and bases into the robotic mesh of everyday life. Robotic sensors, robotic algorithms, and robotic swarms, resonating through the folds and surfaces of the city, will act together in a robotic manhunt, targeting the abstract trajectories of individual persons. Released from the decisively human calculations of targets, this ubiquitous robotic policing would implement a post-political war forever, “an uninterrupted, fluid, shaping and oscillating magma of conflict that is constantly forming and deforming according to changing impulses and threat cases.”

A robotic empire

The American military and the broader scientific community regularly imagine, construct, and script robotic futures. These are not innocent or speculative projections: they must be considered performative. Robotic futurism prepares and legitimizes conditions for investment, research and development, and state (in)security now. This article has constructed its own futurism: a futurism in which the American empire, geopolitics, and warfare are radically transformed by robotics. Its initial contribution was to map a distinct set of imagined future states onto the trajectory of the empire. In doing so, I do not claim that this exact future will come to pass—but rather, a set of conditions that contain this future (and others like it) are now imagined, researched, and implemented. Futurisms are nonlinear and open to unpredictable states. For this reason, it is vital that scholars, writers, activists, scientists, and artists intervene in the uneven geographies they mobilize.

Empires have risen and fallen with the evolution of land, naval, and air power. Analyzing the roadmaps, forecasts, and concerns of the American defense community, this article investigates the rise of robotic power and the possible future of warfare, geopolitics, and the U.S. empire. Empire is not a spectacular monolith: it is a heterogeneous array of bodies and machines, neurons and algorithms, and the fragmented warscapes of more-than-human (in)security. Indeed, robots possess a disruptive ontological quality that unsettles easy predictions about the future. This uncertainty is compounded by the globalization of robots among armies, police forces, and terrorist groups around the world, which will transform the U.S.-led robotic order of things. This issue is particularly serious, warn experts, “when one considers that in the future many countries may have the ability to build, relatively cheaply, entire armies of Kill Bots capable of conducting autonomous warfare.”

The American empire is shifting, slowly and never completely, from a regime of warfare based on human enhancement—soldiers extended as tool-beings—toward an empire of robotic autonomy. Swarms of autonomous robots are thus set to transform the spaces, logics, and agents of state violence. From satellites to improvised explosive devices and unmanned Reaper aircraft, objects continuously reshape a new war terrain. […] The possibility of realizing this kind of geopolitical future depends on the capacity (and resources) of the American military to install a robot world of artificial topologies across the entire planet. In contrast to the civilizing missions of 19th-century empires, the American empire projects a vision of the future that demands capital—an empire of robots fed by the diffuse techno-colonization of the world of life.

This future includes the empire’s penetration into planetary technology: a robotic grid… Future robotics, integrated throughout society, alongside ubiquitous sensing, computers, and the Internet of Things, will blur the boundaries between military, police, and commercial robotics, as well as everyday devices… We are only at the dawn of implementing such an extensive robotic network… By delegating the act of killing to artificial agents, violence—at least from the perspective of the American military—will become a mechanical exercise, like building a bridge, designed and executed by robots. In this sense, robotic warfare is alienated because the act of violence operates without broad human involvement. As a study funded by the American Department of Defense predicts, “in the long term, robotic soldiers may evolve and be fully developed, particularly by richer countries.” Such a rise of robotic soldiers embodies the triumph of technology over the populace. As Tom Engelhardt argues, “think about how we’re moving from a citizen army to a robotic and ultimately robot army… We’re heading toward an ever-greater delegation of war to things that cannot protest, cannot vote with their feet (or wings), and for which there is no ‘home front’ or even home.” An empire of indifference fighting with legions of imperial robots.

Original title: Robot Wars: US Empire and geopolitics in the robotic age

Author: Ian G.R. Shaw

Translation: Harry Tuttle