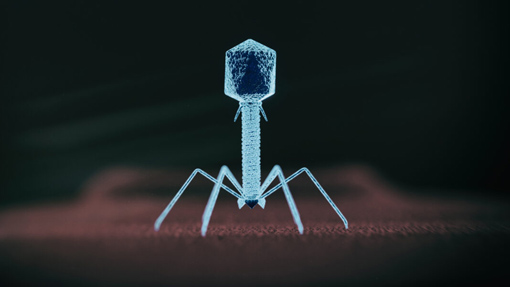

They are viruses. They are called (and are) bacteriophages: they feed exclusively on bacteria. Given that many infections (in the human body), some particularly serious, are caused by bacteria, bacteriophages would be an ideal treatment solution. This indeed proved to be the case: in post-revolutionary Russia, when the West declared a boycott on supplying antibiotics to the Bolsheviks, Lenin ordered research into bacteriophages. The research was successful and for many years saved lives there. But their “problem” was crucial: they were a cheap medical solution and, above all, a rival to the emerging antibiotics (and the first Western pharmaceutical companies). Consequently, bacteriophages were never studied or used in the West.

Not anymore! A new study published a few months ago in the journal Nature Communications concerns the construction of artificial virus vectors, using a kind of “assembly-line” technique that allows the delivery (into bodies) of large biomolecular agents, such as, for example, 171,000 DNA base pairs, thousands of protein molecules, and RNAs. Aiming at cut-and-paste on human DNA (recombination or replacement of genes, modification or silencing of their expression), the research team redesigned the structural features of the bacteriophage T4 so that it can fulfill such tasks—provided, of course, it is introduced into a set of cells, that is, into a body.

All for the good of humanity?