The real danger with artificial intelligence is not its evil, but its competencies.

In our parts, public discourse is either fixated on the past (the more distant, the better...) or on a present so intensely mythologized and distorted that it imposes inertia. Yet the future is here - even in this provincial corner of the planet. Artificial intelligence, in some of its more “light” forms, is already present - from search engines to cyberspace, and all the way to the very near Internet of Things. And AI will become even more everyday when household robots of various kinds and uses start becoming commonplace.

Elsewhere, of course, people are already grappling with this technological (and not only) future that is already present, and its implications - technical, cultural, ideological, political. The quote at the beginning is from Stephen Hawking. However, such weighty concerns wouldn’t require the authority of such a high-level expert to be highlighted: machines are, in themselves, “beyond good and evil”... But what happens - and what will happen - with their programming?

Ethical concerns and corresponding fears about artificial/machine intelligence usually revolve around the question of whether “smart robots” might, somehow, somewhere, someday, destroy the human species. This kind of ethics treats artificial/machine intelligence and robots fetishistically - as autonomous Beings (with a capital B) with their own will. If modern machines appear to have “will” (or even “feelings”), it is only due to ignorance of how they have been designed and how they function. And this ignorance, in turn, stems from the modern (capitalist) division of labor and knowledge.

After 40, 50, 60, or 70 years of research, trials, failures, and successes, algorithmic complexity (and what has become algorithmically possible) is indeed impressive. “Machines that learn on their own” - who would have imagined such a formulation, which is formally accurate? But what “learning” means in the context of generalized informatization is another matter. Just think of it as “the same” as animal learning, and cold sweat will start to break out.

There is an issue that, in a way, constitutes a key element of Hawking’s (and not only) concern regarding the “competencies of artificial intelligence.” It is not the machine’s “intelligence,” but its error.

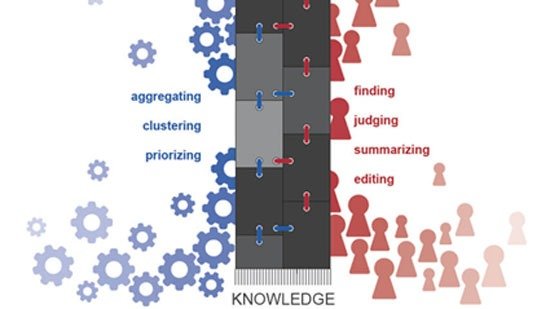

We know the example of Watson, the “platform” developed by IBM engineers. It is an impressive feat of “artificial intelligence” that has defeated the best human contestants on the American TV quiz show Jeopardy! The Watson machine seems to understand questions that aren’t even phrased as questions; and by exploiting its massive data base with stunning speed, it provides answers in no time. At least when the questions are of an encyclopedic nature - that is, about “knowledge.”

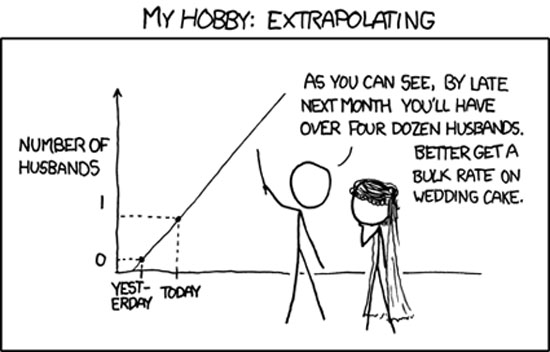

The issue is: what does Watson answer when it makes a mistake? It may be rare, but it does happen. And when Watson is wrong, its answers are grotesquely wrong! For example: to the question “the ocean separating the Old and New Worlds” (answer: Atlantic), if Watson errs, it won’t answer “Indian,” as a poor geography student might. It would answer something like “Vassilis Papakonstantinou”! Because while scanning its enormous data base, it “found” a line from a love song that goes: “An ocean divides our worlds, I am yesterday and you are tomorrow.” (There’s no such line - it’s just an example!)

Such is the electronic and programming complexity of “artificial intelligence” that when it makes an error, it’s highly likely that the mistake will be so grotesque that no programmer could have foreseen it in advance to prevent it. And that’s where the issue of “competency,” as pointed out by Hawking, arises. He has spoken about it - even giving examples: “Imagine a hydroelectric dam managed by a system of ‘smart machines’ with a high degree of artificial intelligence... These aren’t simple switches. Their job is to constantly collect and process data [‘the machine learns on its own’]. That’s the point. If, for whatever reason, the AI makes an erroneous assessment of some new data and its combination with previous data, and opens the dam? Obviously, the consequences would be catastrophic for thousands of people.”

What Hawking essentially means (and it’s the truth) is that no matter how “smart” machines become, they should never be entrusted - without direct human oversight and the ability to override - with competencies and functions where a “mistake” would be costly.

But which ones are those? This is a unprecedented question - one that, if we’re not mistaken, has never before been faced in the history of our species. It’s conceivable that the authority to press the “red button” (to initiate nuclear war) would never be given to a machine, no matter how intelligent it might be considered. But that’s an easy and reasonable answer for many reasons. The harder question is: how will current or future capitalist activities - central or otherwise - be evaluated and ranked in order to set limits?

These are not ethical questions that allow for idle chatter...

Ziggy Stardust

“free” as in “free software”: a small tribute to free software

the fourth example(;): the mechanical mediation of scientific thought

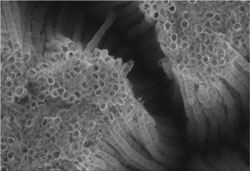

nanotechnologies: some known unknowns…

The Matrix: digital messiahs and the metaphysics of the bioinformatics paradigm

the bleeding materiality of “immaterial” capitalism