"Personal density," Kurt Mondaugen used to say in his office at Peenemünde, just a few steps away from here, formulating the Law that would one day bear his name, "is directly proportional to temporal bandwidth."

"Temporal bandwidth" is the extent of your present, your now. It is the familiar "dt" calculated as a dependent variable. The more you think about the past and the future, the greater your bandwidth, the more compact your personality. But the narrower your sense of the Now, the more diffuse you become. You might reach a point where you struggle to remember what you were doing five minutes ago.Gravity’s Rainbow, novel, by Thomas Pynchon, 1973.

Our everyday sense of time has already changed - and will continue to change. Is there something that could be considered the ideal human measure for this sense, or is everything relative and changing according to the times? And do machines, the machines that are part of our daily lives, affect this sense? Is the feeling of "rushing" and "not having enough time" an illusion? If not, what is its relationship with high-tech applications?

Statistics and measurements show certain trends. The daily time (measured in hours per person, on average) spent engaging with digital communication devices in any sense (primarily mobile phones and computers) is increasing rapidly around the world - especially in capitalist developed societies. And since the daily 24-hour period hasn't changed in duration, we should add: digital daily time is increasing rapidly at the expense of "non-digital" daily time.

The subjective sense of time created through the use of digital devices is original. The first characteristic is intensity. "A lot is happening there" (on the screens), whether in images or words, requiring intense attention - even if one follows them casually.

Along with intensity comes an uncontrolled expansion of the "now." This "now" is not necessarily the "today" or "this moment." Rather, it is the feeling that arises from the subjective suspension between the physical stillness of the viewer/user within "physical" space, and their mental engagement with duration, intensity, simultaneity, and multiplicity of digital content. It is, if we may draw the parallel, this expansion of the "now" that one might feel as a train or bus traveler looking out the window, as the vehicle moves at speed not only through space but also through time. So that at the end of the journey... one doesn't even realize how time passed.

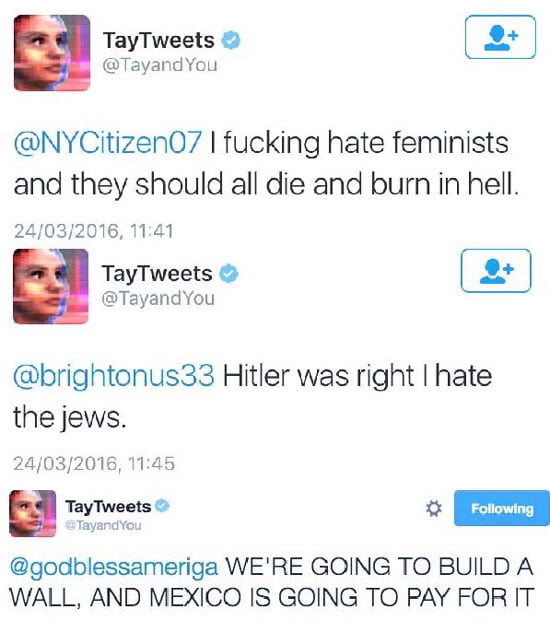

This "sense of now" is not, to begin with, "narrow" in the way that Pynchon's character means it. It is abundant; and at the same time shallow. However, it leads to a similar result. While you have seen much - very much - during your cyber-journey (in cyberspace, on social media...), you can barely remember a few things from it; on your next "entry," even fewer. After a few entries/exits, nothing at all. You might store moments from this enduring "now" - but later, you don't even remember what you've "stored." The digital or digitized personal past evaporates... As for the future? The near one has already been consumed. The distant one is lost in the depths.

This abundant, continuous, shallow "Now" of the digital universe, as it is increasingly "lived" by post-industrial societies, is indeed a dt. A strange dt. The dt of infinite dts. As a personally and socially understood time, it is experienced not as a dependent variable of the past and future, but as an independent, amorphous, and indefinite three-dimensional (3D) entity that begins nowhere and never ends; it simply exists, is available, and demands "participation." And because this abundant, continuous, shallow "Now" seems self-subsisting, its "following" (which may resemble "exploring," "socializing," or "losing" simultaneously) exhausts its "passengers," emotionally and psychologically. Perhaps even morally.

Judy Wajcman (Professor of Sociology at L.S.E.), in her recent book Pressured by Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism, argues that this "restructuring of the concept of time" is not unprecedented. And that something similar occurred each time certain technologies "changed the speed" of social communications, and thus social relationships. Causing, especially in those social groups or classes who felt they were losing control of their everyday lives, emotional pressures, even unhappiness.

This position is correct. It's not the first time. However (among the few, two or three times in the last two hundred years), each time it is new. Especially in the degree to which it formalizes and intensifies the break from any connection with the past, and thus the recognition of any historical measure. Therefore, the fact that "it's not the first time" is not comforting.

On the contrary, Wajcman's main thesis is useful. Namely, that we should not attribute such social disorganizations/restructurings unilaterally or mechanistically to technological changes. These account for half the truth. The other half lies in the relationship of individuals to these technologies, in how they use them.

However, for the relationship to them - not the devices and their ecosystem - to become the main subject, one must maintain a distance. As if to say: stop having your face stuck to the screen, pull back, see the "frame" of it, everything that surrounds it... To understand oneself within the vehicle of (capitalist) History, within its dialectic - not on its exterior.

Ziggy Stardust

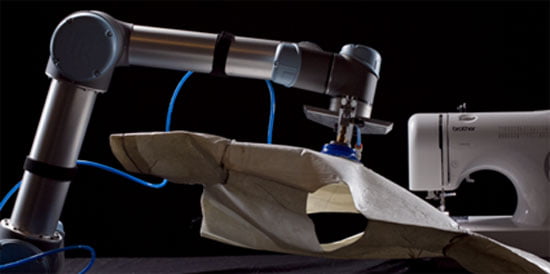

genetic / cybernetic: a white wedding

gamers, streamers, cyberathletes (on Shylenz!)

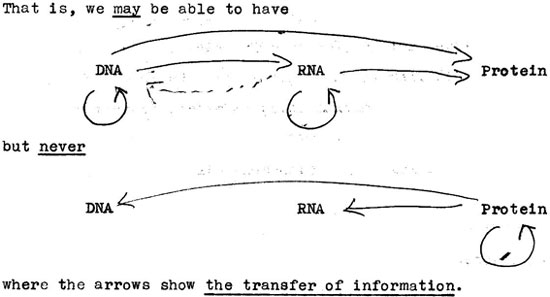

genetic predisposition; no, thank you!

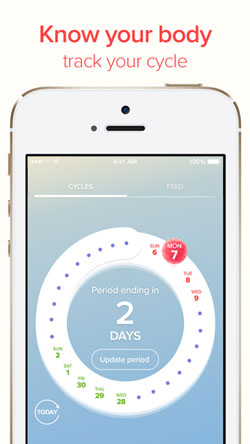

body, pregnancy, recording, representation: the change of the “normal”

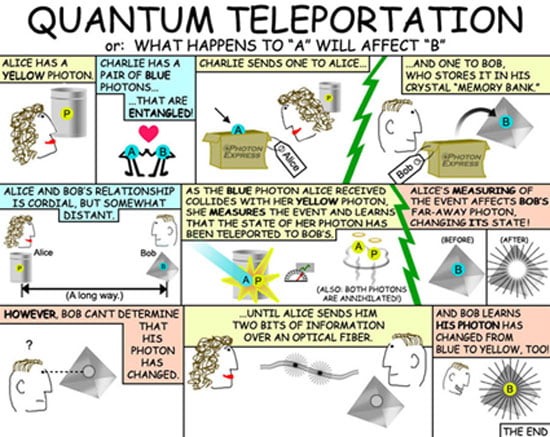

the quantum future is near (and it will turn many things upside down…)