sabotage > A useful historical reference, to begin with. The word “sabotage,” although English in form, is of French origin and has been associated with wooden shoes (sabots) that workers allegedly threw into machinery in the 19th century to destroy them. It’s a nice legend, but there are no records confirming it. Still, even the documented truth about the term is fascinating.

In his 1913 book Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism and Socialism, the socialist and reformist John Spargo writes that the French term sabotage first emerged in the 1890s and is attributed to the anarchist Émile Pouget. The earliest written appearance of the term has been traced to a report by Pouget and his fellow anarchist Paul Delessalle in 1897, at a conference of the Confédération Générale du Travail in Toulouse.

In this report, the two anarchists proposed that French labor unions, facing the intensification of industrial mechanization, should adopt a tactic of delays and deliberate errors that had already proven successful among British labor unions. This tactic was popular in Britain under the name Ca’ Canny, a phrase from Scottish colloquial speech meaning “hurry slowly” or “don’t kill yourself.”

Looking for a similar expression, Pouget coined the noun sabotage, derived from the verb saboter, meaning “to make a big fuss by walking with wooden shoes.”

“In France, especially in rural areas,” Spargo writes, “it was long customary to associate the slow, lazy, or careless worker with those who wore wooden shoes, known as ‘sabots.’ The phrase travailler à coups de sabot meant ‘to work wearing sabots,’ which roughly translated to ‘to drag oneself,’ ‘to be sluggish,’ or ‘to be slow and careless.’”

“The idea is obvious,” says Spargo. “The peasant in wooden shoes, working alongside laborers in leather boots, was the very definition of laziness… Thus, the word sabotage, meaning something like ‘to wear wooden shoes,’ was seen as a fitting translation of the British Ca’ Canny.”

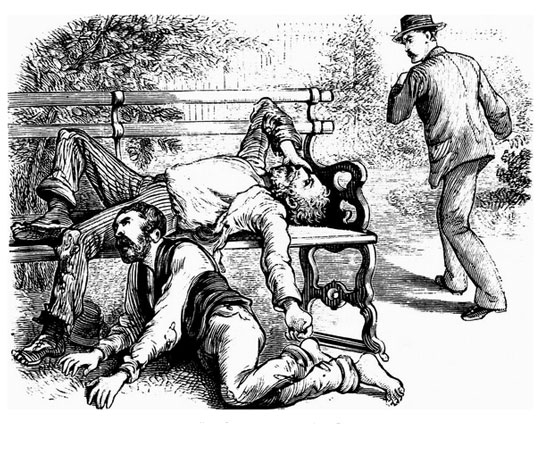

The term was a success. By 1910, it had spread widely among the British working class, so much so that it was even referenced in a local newspaper of the time in relation to a strike - not by British, but by French railway workers. However, in that strike, the railway workers also engaged in “damage.” As a result, sabotage took on a more active, rather than passive, meaning compared to the original image of wooden shoes.

The “brutal rhythms” imposed by machines and the “assembly line” in factories remained the number one target of workers’ resistance throughout the following decades of the 20th century - more so among informal and underground actions than official union ones. The widespread explosion of industrial workers in the 1960s across the capitalist world - the U.S., Europe, Japan - turned upside down what was and wasn’t acceptable as a form of “reaction” from a workers’ perspective. Sabotage, in all its forms - from deliberate delays and minor damage to products, to serious disruptions on the assembly line, and the intentional blocking of production corridors with unfinished goods - became a nightmare for industrial bosses for over a decade: a daily guerrilla war that no wage increase or sweet-talking could stop.

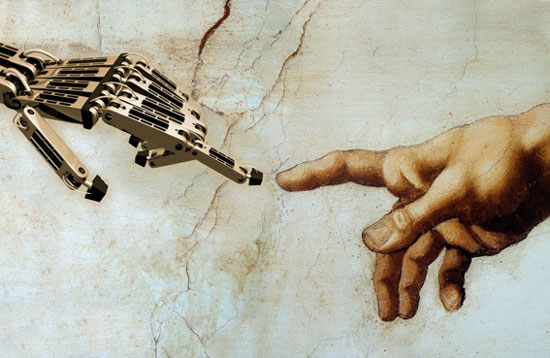

To some, these may seem “outdated,” “irrelevant,” or even “unscientific” - as the mouthpieces of 21st-century technocracy like to mythologize and mythologize again. But the characteristics, specifications, and goals of even the newest, most innovative machines of any kind remain hostile to anything alive - both inside and outside the workplace. This is because these creations are not simply “works of the human spirit” in a general or abstract sense, but only those works that can be funded in advance and then exploited for capitalist gain. They are inherently antagonistic to life. They may be served with the finest wrapping (as has always been the case); they may be praised by cheerleaders as “human progress” (as has always been the case); but they are always acts of expropriation, appropriation, and normalization - designed to enhance control and productivity. Moreover, they are always also weapons - serving a war that is class-based, even if the affected class doesn’t fully grasp the broad meaning of “class war,” or worse, can’t collectively identify or oppose it.

And so we are left with figures like Buffet, who declare: "Yes, a class war is underway - and our class is winning". He’s brutal, but he’s not lying.

Ziggy Stardust

non-compliance is the disease… (behaviorism as a lancet…)

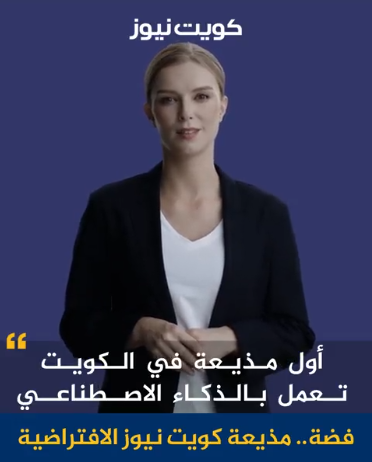

a discussion about artificial intelligence (somewhere far away…)

do machines feel remorse?

the parrot’s question: how far does thought fly?

the great leap: immunity as capital, morbidity as investment